(From Reinhard Kleist’s ‘An Olympic Dream: The Story of Samia Yusuf Omar/SelfMadeHero)

Elizabeth “Biz” Nijdam, University of British Columbia

Comics about refugee experiences are not new. After all, even the superhero created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Superman, is a refugee who landed on Earth after his flight from Krypton.

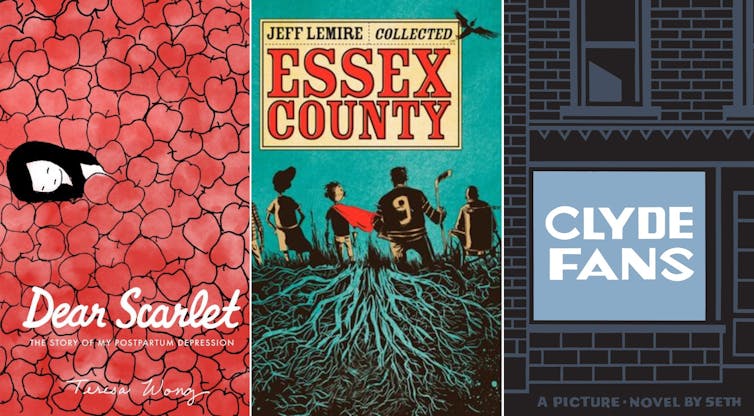

However, recently there has been renewed interest in comics representing migrant experience — namely, that of refugees and asylum-seekers. Since 2011, in particular, and the start of the civil war in Syria, comics and graphic novels have become an important forum for examining global forced migration.

These so-called “refugee comics” range from newspaper comic strips to webcomics and graphic novels that combine eyewitness reportage or journalistic collaboration with comic-book storytelling. These stories are written with the aim of incorporating the points of views of refugees, artists, volunteers or journalists working on-the-ground in displaced communities, war zones and along the migrant journey. They sometimes emerge in collaboration with human rights organizations.

In light of their subject matter, these comic artists contend with complex and distressing themes that are otherwise difficult to represent.

They draw on the traditional comics format, including the medium’s sequential nature, the use of panel walls and a combination of text and image to foster empathy and compassion for the migration journey. In so doing, they aim to give voice to asylum-seekers and refugees, part of 80 million individuals and families forcibly displaced worldwide, whose anonymous images often appear in western media.

Complex issues, narrator’s perspective

These comics are typically drawn by western cartoonists, based on direct testimonies by migrants and refugees or those who have worked with them or encountered them. They are typically not by refugees but about refugees. Scholar Candida Rifkind, who studies alternative comics and graphic narratives, explores how comics about migrant experience often emerge when witnesses to migrant stories grapple with feelings of “shame, guilt and responsibility” to make western society at large more aware of and responsive to refugee realities.

These narratives prompt ethical questions about what it means to tell a story and who has the right or responsibility to do so. While questions about the power relations embedded in how these texts are produced remain, comics on global forced migration are still an important avenue for interrogating the representation of migrants and the socio-political circumstances surrounding their journeys.

These comics also challenge what may otherwise be relayed in mainstream media as the story of a global migrant crisis that has no human face, with perilous effects for migrants who face xenophobia and hate. In Rifkind’s words, they are a kind of intervention into “the photographic regime of the migrant as Other that has emerged as the dominant visual record” of contemporary globalization.

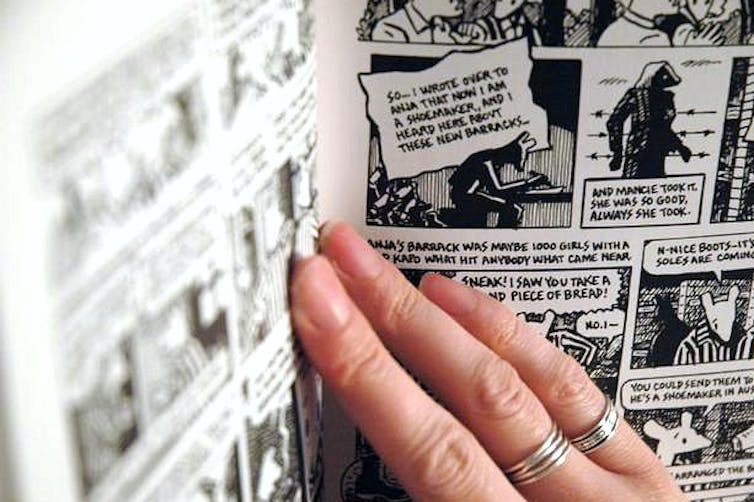

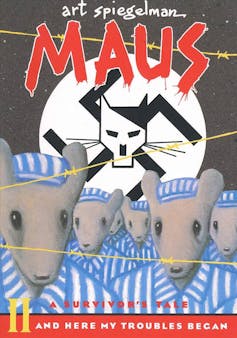

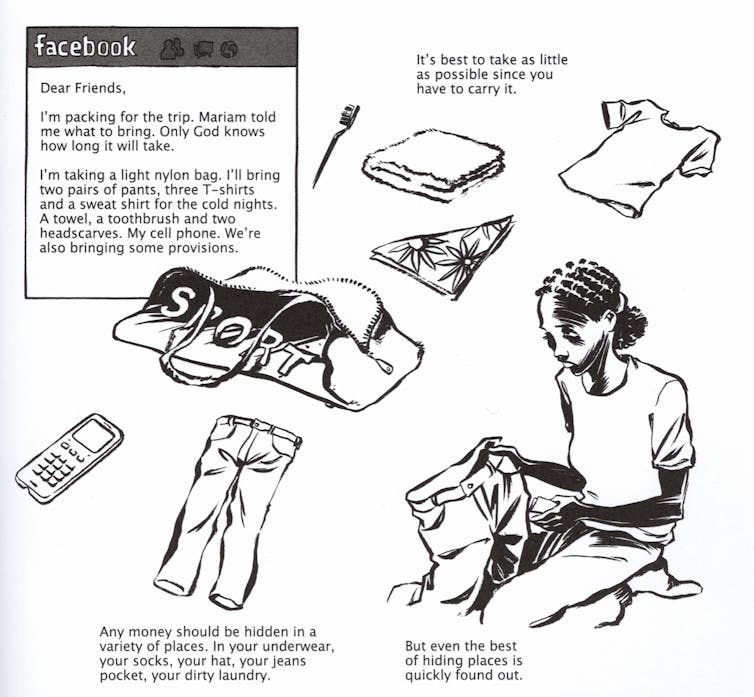

In comics about forced migrant experiences, people experiencing life as refugees become centred as the subjects of their own stories. But cartooning can allow storytellers to represent individuals anonymously, making it easier for people “to give testimony fully and candidly,” while affording them the specificity of their humanity.

There can be consequences for refugees who testify about their circumstances and the oppression and violence they encounter. Photographic evidence of unlawful or undocumented residence in migrant encampments or someone’s journey to seek asylum could in fact jeopardize a person’s safety and end goal.

(HMH Books)

New visual strategies

Notably, comics on forced migration are also inventing new visual strategies to recount refugee experiences. Artists use panel borders to add a layer of storytelling that typically vacillates between the creators’ ability to represent a specific experience, emotion or event and the very inability to portray some forms of trauma and lived experience.

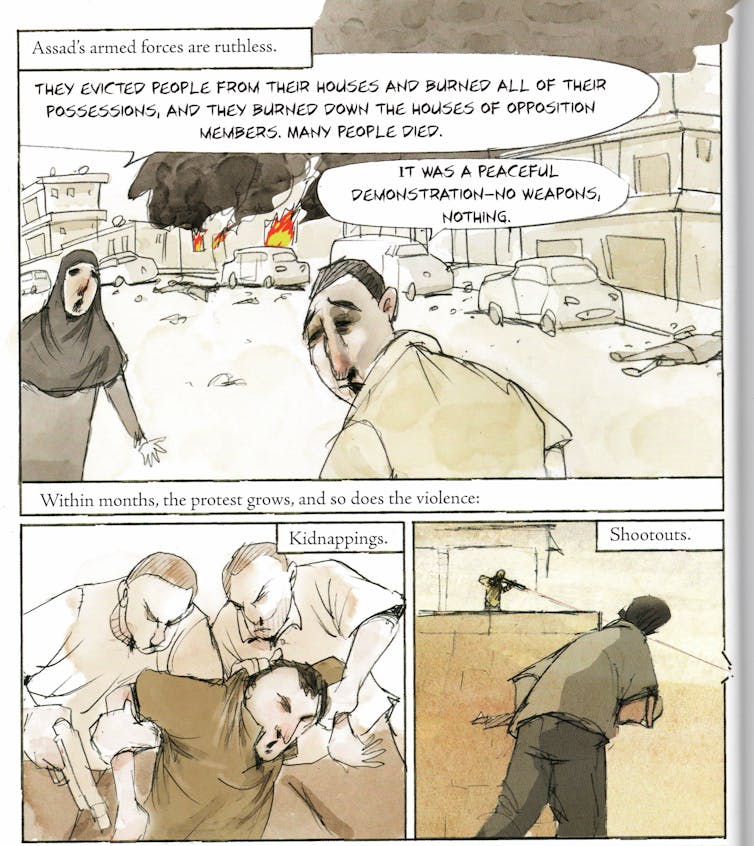

In The Unwanted: Stories of the Syrian Refugees (2018), American author and illustrator Don Brown depicts moments of hardships and hope in the lives of the refugees that Brown met in three Greek refugee camps in Ritsona, in Thessaloniki and on Leros.

The violence encountered by the refugees of Brown’s graphic novel is the only graphic element that breaks through panels. Bullets fracture the panel edges, bombs explode out of the picture planes and toxic smoke rises through the frames.

Brown draws on the convention of exceeding and playing with borders in comics to demonstrate a relationship between violence and transgressing borders. Not only did violence in Syria force many of its citizens to journey in search of safety and freedom; fleeing Syrians also also faced violence and hostility beyond the borders of their homeland on their journeys and where they landed.

(Verso)

The panel borders in Threads: From the Refugee Crisis (2016) by British cartoonist, non-fiction author and graphic novelist Kate Evans are comprised of clippings of delicate lace. Threads is a socio-political and cultural critique rooted in the author’s experience volunteering in the largest though unofficial refugee encampment in Calais, France, which operated from January 2015 to October 2016.

My research has examined how this lace integrated into the comic is more than simply an analogy for the intertwining factors and complex relationships that emerged in Calais. The lacework is a fundamental structuring principle in Evans’ text that engages with the region’s history of lacemaking, Calais’ most essential industry and refugee experience simultaneously.

Frames within stories

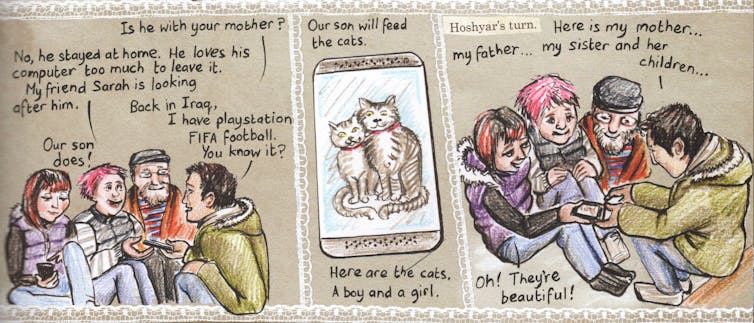

The aesthetics of the smartphone have also begun to play a role in the representation of refugee experiences in comics. Smartphone screens and social media platforms function as frames within some stories.

German graphic designer and cartoonist Reinhard Kleist embeds social media into the comics grid in An Olympic Dream: The Story of Samia Yusuf Omar (2016). The story recounts how Omar, the Somali Olympic runner, died by drowning en route to Italy in 2012.

Some of the story is narrated through Facebook posts based on interviews conducted on that platform with Omar’s sister and a journalist who had interviewed and known Omar.

(SelfMadeHero)

Somalian athletes lifted up Omar’s story to draw attention to the Olympics as a venue to promote awareness about global conflict and peace. In Kleist’s introduction, he writes that too often, “abstract numbers represent human lives.”

This comic and others joins several examples of new media, such as viral videos, mobile games and documentary film that are highlighting the role mobile devices can play during the migration journey.

Through their personal stories, comics on forced migration humanize refugee experience. This category of graphic narrative also offers opportunities for articulating the complexity of refugee experience through the narrative techniques and visual strategies of comic art.![]()

Elizabeth “Biz” Nijdam, Assistant Professor (without review) of German, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.