The link below is to an article that takes a look at writing Dystopian novels during Dystopian times.

For more visit:

https://blog.bookbaby.com/2020/10/writing-dystopian-novels/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at writing Dystopian novels during Dystopian times.

For more visit:

https://blog.bookbaby.com/2020/10/writing-dystopian-novels/

Troy Potter, University of Melbourne

COVID-19 is changing the way we live. Panic buying, goods shortages, lockdown – these are new experiences for most of us. But it’s standard fare for the protagonists of young adult (YA) post-disaster novels.

In Davina Bell’s latest book, The End of the World Is Bigger than Love (2020), a global pandemic, cyberterrorism and climate change are interrelated disasters that have destroyed the world as we know it.

Like most post-disaster novels, the book is more concerned with how we survive rather than understanding the causes of disaster. As such, we can read it to explore our fears, human responses to disaster and our capacity to adapt.

Kelly Devos’s Day Zero (2019), and the soon to be released Day One (2020), use cyberterrorism as the disaster. Like Bell’s novel, Day Zero focuses more on how the protagonist, Jinx, maintains her humanity when she must harm or kill others in order to keep herself and her siblings alive.

A form of speculative fiction, YA post-disaster writing imaginatively explores causes and responses to apocalyptic disasters. (Some readers categorise YA juggernaut The Hunger Games – and the recently released prequel – as dystopian rather than post-disaster – others think it’s both.)

Many YA novels in this genre explore issues of survival and humanity following a catastrophe. In YA post-disaster novels, teenage protagonists must learn to exist in a fractured world with little support from elders.

When they are explained, the fictional causes of catastrophe can illustrate social concerns of times they were written in. Because of this, YA post-disaster books allow us to reflect on our current beliefs, attitudes and fears.

Davos’s Day Zero can be read as commenting on contemporary concerns about cyberterrorism and political corruption. Bell’s The End of the World Is Bigger than Love expresses similar anxieties, but is also prescient given the current pandemic.

War is the cause of disaster in Glenda Millard’s A Small Free Kiss in the Dark (2009) and John Marsden’s Tomorrow series. While Millard’s novel raises questions about homelessness, Marsden’s series expresses an anxiety about invasion from Asia. The author has expressed regret about this aspect of the books since their publication.

A latent xenophobia is also present in Claire Zorn’s, The Sky So Heavy (2013), in part because the nuclear disasters are attributed to “regions in the north of Asia”. Passive ideologies of racism that pervade some YA post-disaster novels are problematic, as are other underlying ideals that promote any form of discrimination.

Read more:

Young adult fiction’s dark themes give the hope to cope

Literary texts that reinforce fear about Asia, particularly China, are especially problematic in the context of coronavirus, which reportedly saw an increase in racist attacks.

Panic buying and the stockpiling of goods during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak established an “us against them” dichotomy in our “struggle to survive”, reminiscent of YA post-disaster fiction.

Not everyone hoarded food and items for themselves though. Others showed compassion, donating toilet paper and food to those in need. Because of this, we were confronted with questions about how we want to survive.

YA post-disaster novels allow us to explore similar questions of humanity. In these fictional worlds, teenage characters are faced with moral dilemmas about who to help and who to harm. How does someone look out for themselves while still expressing empathy and consideration for others? How can characters maintain their humanity if their survival means another’s suffering or death?

Tied up with the question about how we survive, then, is who survives. The protagonist, Jinx, in Day Zero is continually faced with this dilemma. As she flees the corrupt government, Jinx must decide who to help, and how.

While Jinx readily uses violence to overcome her aggressors, she eventually must shoot to kill to save her stepsister. Doing so, Jinx loses a part of herself and becomes “something else”; she must now reconcile her actions with her sense of self.

Read more:

Friday essay: why YA gothic fiction is booming – and girl monsters are on the rise

It’s not so far from the choices medical professionals in Italy, the United States and elsewhere have had to make about who to treat due to limited ventilators and a rapid influx of patients.

No matter the cause of catastrophe, the literary exploration of questions of survival provides opportunities for teenagers, parents and teachers to discuss a range of contemporary issues, including humane responses to disaster.

Given the current crisis we are in, perhaps it is time to critically read more YA post-disaster novels. If they hold up a mirror to our current attitudes and behaviours, they can help us reflect on our humanity, and on what and who we think matters.![]()

Troy Potter, Lecturer, The University of Melbourne, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Katherine Shwetz, University of Toronto

Masked people standing six feet apart. Empty shelves in the supermarket. No children in sight outside the school during recess.

The social upheaval caused by COVID-19 evokes many popular dystopian or post-apocalyptic books and movies. Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 crisis has sent many people rushing to fiction about contagious diseases. Books and movies about pandemics have spiked in popularity over the past few weeks: stuck at home self-isolating, many people are picking up novels such as Stephen King’s The Stand or streaming movies such as Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion.

Yet no one seems to fully agree on why reading books or watching movies about apocalyptic pandemics feels appealing during a real crisis with an actual contagious disease. Some readers claim that contagion fiction provides comfort, but others argue the opposite. Still more aren’t totally sure why they these narratives feel so compelling. Regardless, stories about pandemics call to them all the same.

So what, exactly, does pandemic fiction offer readers? My doctoral research on contagious disease in literature, a project that has required me to draw from both literary studies and health humanities, has taught me that a contagious disease is always both a medical and a narrative event.

Pandemics scare us partly because they transform other, less concrete, fears about globalization, cultural change, and community identity into tangible threats. Representations of contagious diseases allow authors and readers the opportunity to explore the non-medical dimensions of the fears associated with contagious disease.

Pandemic fiction does not offer readers a prophetic look into the future, regardless of what some may think. Instead, narratives about contagious disease hold up a mirror to our deepest, most inchoate fears about our present moment and explore different possible responses to those fears.

One novel that has grown in popularity over the past few weeks is been Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven. Mandel’s novel follows a troupe of Shakespearean actors touring a post-apocalyptic landscape in a North America decimated by contagious disease.

Mandel’s novel serves as a test case for understanding the cultural response to COVID-19. The current pandemic sharpens fears about the relative instability of our communities (along with posing an immediate threat to our health, of course).

Coverage of Station Eleven claims that the text is uniquely relevant to the COVID-19 situation. This response treats Mandel’s novel as through it predicts what will happen as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. Some news outlets even call the novel a “model for how we could respond” to an apocalyptic pandemic.

This is not the case. Station Eleven draws from apocalyptic literature, a narrative form that tells us more about the present than the future. Mandel herself has called Station Eleven more “a love letter to the world we find ourselves in” than a handbook for a post-apocalyptic future Indeed, Mandel herself publicly suggested that her novel is not ideal reading material for the present moment.

In fact, Station Eleven spends almost no time focused on the actual epidemic. The vast majority of the novel takes place before and after the outbreak. The medical details of the disease are less important than the rhetorical impact of the destructive virus.

Those fears in Station Eleven coalesce in scenes where communities must shift how they understand their relationship to one another. Characters stranded in an airport hangar, for example, must work together to build a new society that accommodates their shared traumatic experience. The pandemic in Mandel’s novel dramatically emphasizes to the characters not how to respond to a virus but, instead, how powerfully interconnected they truly are — the same thing COVID-19 is doing to us right now. Part of what pandemic fiction illuminates is how fears of invasion and the perceived threat of outsiders can diminish our humanity.

A virus crosses the boundary of your body, invading your very cells and changing your body on an incredibly intimate level.

It is unsurprising, then, that scholars see a strong relationship between contagious diseases and community identity. As anthropologist Priscilla Wald puts it, contagious disease “articulates community.” Pandemics emphasize how our individual bodies are connected to our collective body.

Left unchecked, the rhetorical implications of these narratives can lead to discriminatory behaviour or racism.

In Station Eleven, the villain — a cult leader prophet — continually denies his fundamental connection to those around him. He claims that he and his followers survived the epidemic because of their divine goodness and not because of luck. As a result, he engages in violent, abusive behaviours intended to quash the fear associated with interdependence — a common response to this fear.

The prophet in Station Eleven does not survive the novel; the surviving characters are the ones who accept that they cannot extricate themselves from connection to other people.

Contagious diseases — both in fiction and in real life — remind us that the social and cultural boundaries we use to structure society are fragile and porous, not stable and impermeable.

Although these works of literature cannot prophecize an imminent post-apocalyptic future, they can speak to our present.

So if reading a book about a pandemic appeals to you, go for it — but don’t use it as an instructional manual for an outbreak. Instead, that work of fiction can help you better understand and manage how the virus amplifies complex, diverse and multi-faceted fears about change in our communities and our world.![]()

Katherine Shwetz, PhD Candidate and Course Instructor, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bernadette McBride, University of Liverpool

We are headed towards a future that is hard to contemplate. At present, global emissions are reaching record levels, the past four years have been the four hottest on record, coral reefs are dying, sea levels are rising and winter temperatures in the Arctic have risen by 3°C since 1990. Climate change is the defining issue of our time and now is the moment to do something about it. But what?

Society often looks to culture to try and make some sense of the world’s problems. Climate change challenges us to look ahead, past our own lives, to consider how the future might look for generations to come – and our part in this. This responsibility requires imagination.

So, it is no surprise that a literary phenomenon has grown over the past decade or two which seeks to help us imagine the impacts of climate change in clear language. This literary trend – generally known by the name “cli-fi” – has now been established as a distinctive form of science fiction, with a host of works produced from authors such as Margaret Atwood and Paolo Bacigalupi to a series of Amazon shorts.

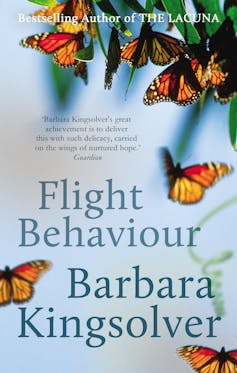

Often these stories deal with climate science and seek to engage the reader in a way that the statistics of scientists cannot. Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behaviour (2012), for example, creates emotional resonance with the reader through a novel about the effects of global warming on the monarch butterflies, set amid familiar family tensions. Lauren Groff’s short story collection Florida (2018) also brings climate change together with the personal set amid storms, snakes and sinkholes.

Cli-fi is probably better known for those novels that are set in the future, depicting a world where advanced climate change has wreaked irreversible damage upon our planet. They conjure up terrible futures: drowned cities, uncontainable diseases, burning worlds – all scenarios scientists have long tried to warn us about. These imagined worlds tend to be dystopian, serving as a warning to readers: look at what might happen if we don’t act now.

Atwood’s dystopian trilogy of MaddAddam books, for example, imagines post-apocalyptic futurist scenarios where a toxic combination of narcissism and technology have led to our great undoing. In Oryx and Crake (2003), the protagonist is left contemplating a devastated world in which he struggles to survive as potentially the last human left on earth. Set in a world ravaged by sea level rise and tornadoes, Atwood revisits the character’s previous life to examine the greedy capitalist world fuelled by genetic modification that led to this apocalyptic moment.

Other dystopian cli-fi works include Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife (2015), and the film The Day After Tomorrow (2004), both of which feature sudden global weather changes which plunge the planet into chaos.

Dystopian fiction certainly serves a purpose as a bleak reminder not to act lightly in the face of environmental disaster, often highlighting how climate change could in fact compound disparities across race and class further. Take Rita Indiana’s Tentacle (2015), a story of environmental disaster with a focus on gender and race relations – “illegal” Haitian refugees are bulldozed on the spot. A. Sayeeda Clarke’s short film White (2011), meanwhile, tells the story of one black man’s desperate search for money in a world where global warming has turned race into a commodity and circumstances lead him to donate his melanin.

It is this primacy of the imagination that makes fictional dealings with climate change so valuable. Cli-fi author Nathaniel Rich, who wrote Odds Against Tomorrow (2013) – a novel in which a gifted mathematician is hired to predict worst-case environmental scenarios – has said:

I think we need a new type of novel to address a new type of reality, which is that we’re headed toward something terrifying and large and transformative. And it’s the novelist’s job to try to understand, what is that doing to us?

As the UN 2019 Climate Action Summit attempts to bring the 2015 Paris Agreement up to speed, we need fiction that not only offers us new ways to look forward, but which also renders the inequalities of climate change explicit. It is also key that culturally we at least try to imagine a fairer world for all, rather than only visions of doom.

When now is the time that we need to act, the rarer utopian form of cli-fi is perhaps more useful. These works imagine future worlds where humanity has responded to climate change in a more timely and resourceful manner. They conjure up futures where human and non-human lives have been adapted, where ways of living have been reimagined in the face of environmental disaster. Scientists, and policy makers – and indeed the public – can look to these works as a source of hope and inspiration.

Utopian novels implore us to use our human ingenuity to adapt to troubled times. Kim Stanley Robinson is a very good example of this type of thinking. His works were inspired by Ursula Le Guin, in particular her novel The Dispossessed (1974), which led the way for the utopian novel form. It depicts a planet with a vision of universal access to food, shelter and community as well as gender and racial equality, despite being set on a parched desert moon.

Robinson’s utopian Science in the Capital trilogy centres on transformative politics and imagines a shift in the behaviour of human society as a solution to the climate crisis. His later novel New York 2140 (2017), set in a partly submerged New York which has successfully adapted to climate change, imagines solutions to more recent climate change concerns. This is a future that is mapped out in painstaking detail, from reimagined subways to mortgages for submarines, and we are encouraged to see how new communities could rise against capitalism.

This is inspirational – and useful – but it is also is crucial that utopian cli-fi novels make it clear that for every utopian vision an alternative dystopia could be just around the corner. (It’s worth remembering that in Le Guin’s foundational utopian novel The Dispossessed, the moon’s society have escaped from a dystopian planet.) This is a key flaw in the case of Robinson’s vision, which fails to feature the wars, famines and disasters outside of his new “Super Venice”: the main focus of the book is on the advances of western technology and economics.

Forward-thinking cli-fi, then, needs to imagine sustainable futures while recognising the disparities of climate change and honouring the struggles of the most vulnerable human and non-humans. Imagining positive futures is key – but a race where no one is left behind should be at the centre of the story we aspire to.

This article is part of The Covering Climate Now series

This is a concerted effort among news organisations to put the climate crisis at the forefront of our coverage. This article is published under a Creative Commons license and can be reproduced for free – just hit the “Republish this article” button on the page to copy the full HTML coding. The Conversation also runs Imagine, a newsletter in which academics explore how the world can rise to the challenge of climate change. Sign up here.![]()

Bernadette McBride, PhD Candidate in Creative Writing, University of Liverpool

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at the branch of fiction known as dystopia.

For more visit:

http://lithub.com/dystopia-for-sale-how-a-commercialized-genre-lost-its-teeth/