Joseph Prezioso/AFP via Getty Images

Ani Kokobobo, University of Kansas

Nihilism was notably cited during U.S. Senate deliberations after rioting Trump supporters had been cleared from the Capitol.

“Don’t let nihilists become your drug dealers,” exhorted Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse. “There are some who want to burn it all down. … Don’t let them be your prophets.”

How else to describe the incendiary rhetoric and grievances that Donald Trump has peddled since November? What else to call the denial of the electorate’s will and his deep disdain for American institutions and traditions?

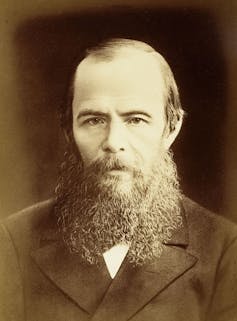

In 2016, I wrote about how Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky had, in his work, explored what happens to society when people who rise to power lack any semblance of ideological or moral convictions and view society as bereft of meaning. I saw eerie similarities with Trump’s actions and rhetoric on the campaign trail.

Fast-forward four years, and I believe the warnings of Dostoevsky – particularly in his most most political novel, “Demons,” published in 1872 – hold truer than ever.

Although set in a sleepy provincial Russian town, “Demons” serves as a broader allegory for how thirst for power in some people, combined with the indifference and disavowal of responsibility by others, amount to a devastating nihilism that consumes society, fostering chaos and costing lives.

Power for power’s sake

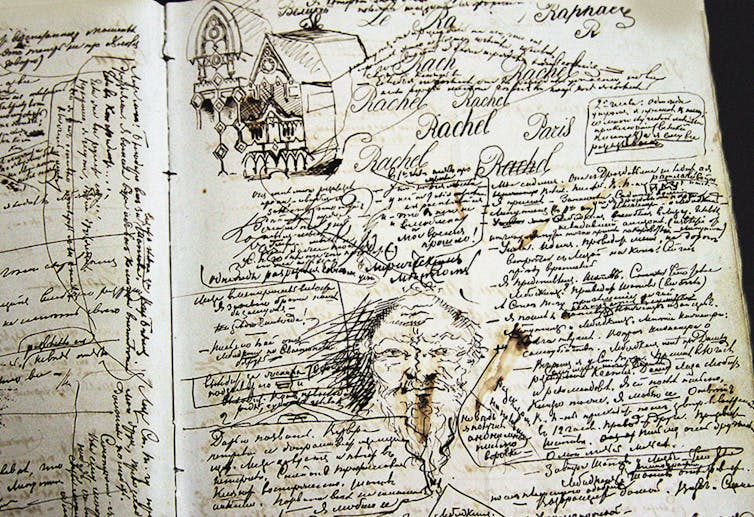

Before “Demons,” Dostoevsky had been writing a novel about faith, “The Life of a Great Sinner.”

But then a disturbing public trial spurred him in a more overtly political direction. A young student had been murdered by members of a revolutionary group, The Organization of the People’s Vengeance, at the behest of their leader, Sergei Nechaev.

Dostoevsky was appalled that politics could be dehumanizing to the point of murder. His focus turned not only to moral questions but also to political demagoguery, which, he argued, if left unchecked, could result in devastating loss of life.

adoc-photos/Corbis via Getty Images

The result was “Demons.” It featured two protagonists: Pyotr Verkhovensky, a former student with no political convictions beyond a lust for power, and Nikolai Stavrogin, a man so morally numb and emotionally detached that he is incapable of purposeful action and stands idly by as violence engulfs his society.

Through these two figures, Dostoevsky tells a broader story about the many flavors of nihilism. Pyotr infiltrates the town’s local social circles, recruits a group of disciples to a revolutionary group and spins lies to band them together so they may do his bidding. Pretending to lead a broad movement of international socialism, Pyotr manipulates those around him into committing violent acts and insurrection against the local government. As a result, one woman is crushed by a mob, a mother and her baby die from chaos and neglect and a fire breaks out that kills multiple others.

Different townspeople espouse multiple and contradictory ideologies; none translates into purposeful action. Instead, they merely leave characters whiplashed and susceptible to being instrumentalized by Pyotor, the master manipulator.

The allure of feeling something

But Pyotr would not prevail without the nihilism of Stavrogin, a local nobleman.

Many townspeople see him as a leader with a strong moral compass. Throughout the novel, Pyotr seeks to loop Stavrogin into his quest for power by either doing him favors that corrupt him or hinting that he will install him as dictator once he successfully carries out a revolution.

On some level, Stavrogin knows better: He should be protecting the town and its people. He ultimately fails to do so, out of sheer despondence and because of the emotional appeal of chaos and violence have for him; they seem to jolt him out of the ennui he often appears to feel.

When given the chance to restrain and turn in to the authorities the escaped convict who perpetrates most of the violence in town, Stavrogin captures him only to eventually let him go. “Steal more, kill more,” he says to a criminal who has already admitted to killing and stealing. Later, when the political climate gets so heated that it seems an insurrection is imminent, he flees town.

Heritage Images via Getty Images

In surrendering his responsibility to serve as a moral guardian, Stavrogin becomes complicit in Pyotr’s schemes. He ultimately kills himself – perhaps, in part, out of guilt for his passivity and moral indifference.

Among the two men, Pyotr is the authoritarian figure. And he cleverly insists that members of the revolutionary group break the law together, cementing a loyal brotherhood of criminality.

By contrast, Stavrogin is the novel’s empty center, idly standing by while Pyotr incites violence.

He doesn’t help Pyotr. But he doesn’t stop him, either.

From nihilism to annihilation

A range of nihilistic justifications – each successively hollower than the rest – seems to have shaped the violence at the U.S. Capitol.

The homegrown American insurrection lacked any sort of ideological foundation. Most ideas fueling it are negations of persons or facts. The immediate rallying cry of the insurrection was the falsehood that the election was stolen. Beyond denying the will of over 80 million people who voted for Joe Biden, this lie also qualifies not as an ideology, but as an absolute denial of truth.

Other ideas fomenting the insurrection – such as “America first” or “MAGA” and even white supremacy itself – are quintessentially founded on the denial of others, whether they are immigrants, foreign nationals or persons of color.

From what we have learned since, some of Trump’s supporters were even imploring him to “cross the Rubicon,” a reference to Julius Caesar’s initiation of the civil war that eventually transformed Rome into a dictatorial empire, expressing a longing to smash American systems and eviscerate the republic.

The only real purpose that seems to have brought the group together was devotion to Donald Trump, who strikes me as the arch-nihilist in all this, the Pyotr Verkhovensky of this American tragedy. Then there are the other public figures who should have known better, who might have helped stop it all, but couldn’t and didn’t. Some, like Stavrogin, excused themselves and were silent for far too long, as the lie about the election grew bigger and bigger. And others seemed to outright encourage the lie through formalized objections in Congress last week.

Playacting at revolution at the behest of a man seeking to cling to power, the rioters ultimately only managed only to vandalize the building, though they left five people dead in their wake.

Nonetheless, to act violently on the basis of such fictions – and to transgress against the humanity of others for nothing at all – is perhaps the most nihilistic act of them all.![]()

Ani Kokobobo, Associate Professor of Russian Literature, University of Kansas

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.