David Anderson, Swansea University

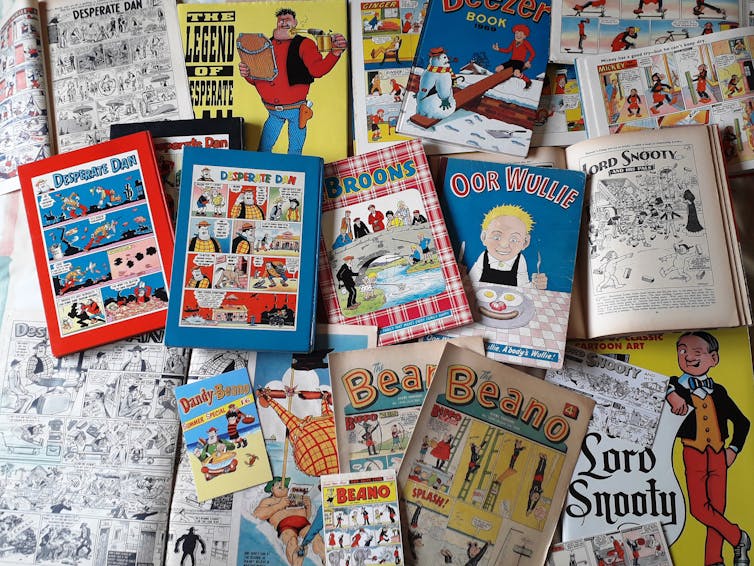

You may not be familiar with the name Dudley Dexter Watkins, but chances are you will recognise his art. Half a century after his death, the work of the talented British comic strip artist and illustrator is as well known, and as much loved, as it has ever been. Characters such as Desperate Dan, who Watkins illustrated for The Dandy comic, and Lord Snooty for The Beano, have remained favourites for many years, their silly antics and predicaments now kept alive by other artists.

This summer, a trail of outdoor statues has been placed across Scotland featuring one of Watkins’ most popular creations, Oor Wullie, who appeared alongside The Broons in The Sunday Post newspaper from 1936 until Watkins’ death in 1969.

Born the son of a lithograph artist in Greater Manchester in 1907, Watkins was just a few months old when his family moved to Nottingham. It was there that his artistic talents were first recognised. Encouraged by his father, Watkins took up a place at Nottingham School of Art. His first opportunity to see his drawings in print came soon after. The chemist Boots, where Watkins worked in the window display department, published his cartoons and illustrations in staff magazine The Beacon.

By 1925, Watkins had moved to Scotland where his work caught the eye of publishing house D.C. Thomson. Aged just 18, he joined the Dundee-based company, an employment that would last more than 40 years. During this time, Watkins created some of Britain’s most iconic comic characters.

In his first decade with Thomson, Watkins worked on a group of boys’ weekly action papers known as “The Big Five” – Adventure, The Rover, The Wizard, The Skipper and The Hotspur. These publications experimented with the comic strip format and focused on sport, school and war adventure stories. Watkins produced many of the front covers for The Big Five, and contributed comic strips to small format supplements that accompanied The Rover and The Skipper.

In 1936, when Thomson produced a supplement to The Sunday Post named The Fun Section, the spikey-haired, dungaree-clad Oor Wullie and the close-knit working-class Broons family were born. Written in Scots dialect, the capers of these characters, drawn weekly by Watkins for more than three decades, still feature in the newspaper today.

The look of these characters has changed little since their first appearance. It is this sense of regularity and reassurance that still arouses nostalgia in generations of readers, fuelled by an inexhaustible range of associated books, clothing and other merchandise.

Read more:

The Sunday Post: how Scotland’s sleepiest newspaper silenced the detractors

Spurred on by the success of The Fun Section, Thomson released two new comics for boys and girls: The Dandy in December 1937 and The Beano in July 1938. These launches brought into being some of Watkins’ most recognisable characters including Desperate Dan, Lord Snooty and Biffo the Bear.

Based on an idea by editor Albert Barnes, cow-pie-eating Desperate Dan, one of Watkins’ most enduring creations, debuted in the first issue of The Dandy. In the black-and-white half-page strip, Dan is seen purchasing a horse that promptly collapses under the cowboy’s considerable weight. Watkins apparently based Dan’s super-sized square-jaw on Barnes’s own chin, and Dan’s exaggerated toughness – he shaves with a blowtorch and shoots a bullet through his hair to part it – personified the robust humour of The Dandy.

Watkins’ peers acknowledged his rare talent. He was said to draw at lightning speed, effortlessly encapsulating the wit and wonder of his distinctive comic characters. Such was the importance of Watkins’ work, he was exempted from active military service during World War II and instead served as a war reserve constable in Fife. In 1946, Watkins began signing and initialling his published work, a privilege afforded to only a few comic strip artists in those days (it also ensured his loyalty to Thomson following attempts by a rival publisher to lure him away from Dundee).

Read more:

How The Beano survived war and the web to reach its 80th birthday

Wartime paper shortages forced The Dandy and The Beano into a fortnightly publishing schedule, but by the 1950s not only had Thomson returned to weekly editions of these comics, it had launched two other, tabloid-style, publications – The Topper and The Beezer. Watkins was tasked with illustrating the front cover characters, introducing Mickey the Monkey and Ginger to a new generation of humour comic fans.

A prolific artist, Watkins’ output extended beyond his Thomson portfolio. Inspired by his Christian faith, he often led Bible discussions and delivered illustrated talks on religious themes to children at the Church of Christ in Dundee. In his spare time, he also drew strip cartoons for Young Warrior, a children’s paper published by the Worldwide Evangelisation Crusade.

Watkins died at his drawing desk in 1969, aged 62. His artwork, particularly his early strips in comics and annuals, have become increasingly collectable, connecting with current trends for childhood nostalgia. While many fans still display the same affection for Watkins’ characters that they felt as children, the way in which we experience comic strip art alters as we grow up. While as children we simply loved how the drawings captured tongue-in-cheek humour, as adults we are able to view with a more mature appreciation the creative endeavour gone into producing them.

Watkins’ work, and his dedication to it, is still highly impressive. Considered a quiet, pious man during his lifetime, Watkins’ lasting fame rests on the high-quality comic artwork and illustrations to which he devoted so much of his life.![]()

David Anderson, Senior Lecturer in Political and Cultural Studies, Swansea University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.