Gerard Lee McKeever, University of Glasgow

The memory of the Ayrshire-born Scottish poet Robert Burns has always been complicated, especially in Dumfries, the town where he died in July 1796. In the years following his untimely demise at the age of 37, literary tourists including Dorothy Wordsworth and John Keats visited this market town in south-west Scotland in search of their hero. What they found, however, was a vision of Burns and of Scotland itself that seemed out of place, difficult to comprehend and yet intensely personal.

Burns’s own relationship to Dumfriesshire was enigmatic from the start. When he arrived to take up the tenancy of Ellisland farm in the summer of 1788, he declared himself in a “land unknown to prose or rhyme”. But Burns’s view of the region would evolve many times. By August of the same year, he was commemorating the Nith Valley’s “fruitful vales”, “sloping dales” and “lambkins wanton”, and had already written back in October 1787 that: “The banks of Nith are as sweet, poetic ground as any I ever saw.”

Shutterstock

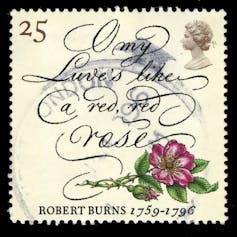

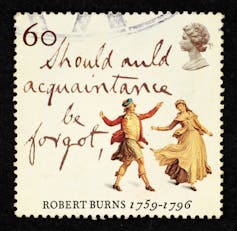

Burns composed some of his best-known work during these years, including what many consider his masterpiece, Tam o’ Shanter. And yet a shift in focus from poetry to songwriting – as he worked to collect, revise and compose lyrics for collections of national song – changed the sense of both place and personality in his writing. In his earlier years, Burns’s poetry had often been intensely self-reflective, rooting a version of himself in the Ayrshire landscape where he was raised. Now, his persona receded into the background due to the inherently communal nature of folksong.

At the same time, Burns’s employment as an excise officer and his eventual poor health in Dumfries would lead 19th-century commentators such as the historian Thomas Carlyle to accuse the town of wasting the poet’s talents through a lack of patronage. That underestimates Burns’s agency as a member of the lower middle class, who took pride in supporting his family independently. Yet still, what emerged was a lingering sense of the Ayrshire Burns as the true Burns, where the Dumfries Burns was only a tragic, diminished echo of himself.

Shutterstock

Poetic pilgrimage

In 1803, Dorothy Wordsworth set off from the Lake District on a tour of Scotland in the company of her brother William and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Among key items on their itinerary was a pilgrimage to Burns sites in and around Dumfries. Yet the poet’s memory would not be easily reckoned with.

In her tour journal, Wordsworth quoted Burns’s own A Bard’s Epitaph – “thoughtless follies laid him low, | And stain’d his name” – to underline the moral failings of a poet already famous for his love affairs and heavy drinking. She wrote:

We could think of little else but poor Burns, and his moving about on that unpoetic ground.

Burns proved an inescapable but difficult presence in Dumfries for Wordsworth. He became representative of a south-west Scotland that defied easy comprehension: neither quite “the same as England” nor “simple, naked Scotland”.

Further north at Ellisland farm, Wordsworth remembered catching a view back home to “the Cumberland mountains”. The idea was taken up by her brother in a poem originally titled Ejaculation at the Grave of Burns, in which William imagined himself and Burns as the hills of Criffel and Skiddaw staring at one another across the Solway Firth. Yet the dead poet remained out of reach, leaving these tourists to their personal musings about Dumfriesshire in the terms of tragedy: a visit to Burns in 1803 was already seven years too late.

Shutterstock

If anything, the situation was even more pronounced in John Keats’s account of his 1818 walking tour, in which Dumfries shoulders much of the blame for the tragic story of this “poor unfortunate fellow”. Keats would find himself disgusted at the tourism industry that had already sprung up at the poet’s birthplace further north in Ayrshire.

But when confronted with the spectacle of Burns’s death, Keats apparently struggled to make much sense of Dumfries at all. Performing a kind of theatrical bewilderment in On Visiting the Tomb of Burns, he wrote that the town seemed “beautiful, cold – strange – as in a dream”.

Memory and imagination

It is difficult to overstate the impact of Burns’s legacy in south-west Scotland, for better or worse. His influence on following generations of poets in the region could be both inspiring and suffocating, while civic pride in his memory took on new forms in Dumfries as elsewhere throughout the 19th century, not least in the extravagant centenary celebrations in 1859.

Shutterstock

Today, when the poet’s birthday is marked on January 25 around the world, many different and contradictory versions of Burns will be remembered. In their complex responses to Dumfries, where the poet’s death has often seemed more tangible than his birth, early literary tourists like the Wordsworths and Keats show that this is nothing new.

After all, the role of a national poet – a vehicle for our thoughts and dreams – underlines how much of both memory and geography is the work of the imagination.![]()

Gerard Lee McKeever, British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.