The link below is to an article that looks at the future of the hardback/hardcover.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/25/book-clinic-why-do-publishers-still-issue-hardbacks

The link below is to an article that looks at the future of the hardback/hardcover.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/25/book-clinic-why-do-publishers-still-issue-hardbacks

The link below is to an article that asks the question, ‘do we really need books anymore?’

For more visit:

https://medium.com/@emilycashour/do-we-really-need-to-read-books-anymore-c8390c8c8448

The link below is to an article that takes a look at authors who grew to hate their own books.

For more visit:

http://lithub.com/13-writers-who-grew-to-hate-their-own-books/

Lauren O’ Hagan, Cardiff University

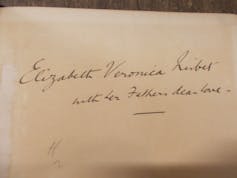

Open up a book from the late 19th or early 20th century and chances are that you will find an inscription inside the front cover. Often, they are nothing more than handwritten names that state who owned the book, though some are a little more elaborate, with personalised designs used to denote hobbies and interests, tell jokes or even warn against theft of the book.

While seemingly insignificant markers of ownership, book inscriptions offer important material evidence of the various institutions, structures and tastes of Edwardian society, and act as tangible indicators of class and social mobility in early 20th century Britain. They can also reveal vast amounts of information on how both attitudes of ownership and readership varied according to geographical location, gender, age and occupation at this time.

My research involves collecting these inscriptions from secondhand books and working with archives to delve into the human stories behind these ownership marks. I am particularly interested in “everyday” Edwardians – the miner, the servant, the clerk – who are so often forgotten by time, yet played an essential role in ensuring Britain ran smoothly during the war years.

My latest work has focused on the stories of the female heroes of World War I. They weren’t fighting on the battlefield but their contributions at home and abroad were nothing short of incredible. Using the inscription marks they left in books, censuses, local history, and Imperial War Museum archives, I have tracked several untold tales, two of which I’ve written about here.

Elizabeth Veronica Nisbet was born in 1886 in Newcastle. The daughter of a colliery secretary, Nisbet was part of the lower-middle class that emerged in Britain at the end of the Victorian era. She studied art at Gateshead College before serving as a nurse with St John Ambulance and the Royal Victoria Infirmary.

In 1913, Nisbet’s father gave her a copy of the biography of cartoonist George Du Maurier, and inscribed it “with dear love”. Du Maurier was well-known for his cartoons in the satirical magazine Punch, which inspired Nisbet’s own artwork. Just one year after receiving the book, World War I broke out and Nisbet headed to France to aid wounded soldiers at St John Ambulance Brigade Hospital in Étaples. This hospital was the largest to serve the British Expeditionary Force in France and treated over 35,000 casualties.

Throughout these troubled times, Nisbet’s passion for art was her salvation: she kept a scrapbook of cartoons, sketches and photos, which provide an insight into wartime Étaples and the vital work of the female nurses. Looking at her artwork, it is clear that she was strongly influenced by the cartoon style of Du Maurier, suggesting that the book remained a treasured artefact to her while she was serving in France.

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Today Nisbet’s work is kept at the Museum of the Order of St John in London. After the war, she returned to Newcastle and worked again as a nurse until the 1920s when she became a full-time artist, travelling regularly to the US and Canada to showcase her work. She died in 1979 at the age of 93.

Born in France in 1876, Gabrielle de Montgeon moved to England in 1901 and lived in Eastington Hall in Upton-on-Severn throughout her adult life. She was the daughter of a count of Normandy and part of the upper class of Edwardian society.

Her affluence is showcased in the privately-commissioned bookplate found inside her copy of the 1901 Print Collector’s Handbook. The use of floral wreaths and decorative banderoles in her plate – both features of the fashionable art nouveau style of the period – mimic the style of many of the prints in her book. This demonstrates the close relationship that Edwardians had between reading and inscribing.

Stepping out of her upper class life, during World War I, de Montgeon served in the all-female Hackett-Lowther Ambulance Unit as an assistant director to Toupie Lowther – the famous British tennis player who had established the unit. The unit consisted of 20 cars and 25-30 women drivers, who operated close to the front lines of battles in Compiegne, France. De Montgeon donated ambulances and was responsible for the deployment of drivers. After the war, she returned to Eastington Hall and led a quiet life, taking up farming, before passing away in 1944, aged 68.

![]() Considering the testing circumstances of war, the survival of these two books (and their inscriptions) is a remarkable feat. While buildings no longer stand, communities have passed on, and grass on the bloody battlefields grows once more, these books keep the memories of Nisbet and de Montgeon alive. They stand as a testimony of the unsettling victory of material objects over the temporality of the people that once owned them and the places in which they formerly dwelled.

Considering the testing circumstances of war, the survival of these two books (and their inscriptions) is a remarkable feat. While buildings no longer stand, communities have passed on, and grass on the bloody battlefields grows once more, these books keep the memories of Nisbet and de Montgeon alive. They stand as a testimony of the unsettling victory of material objects over the temporality of the people that once owned them and the places in which they formerly dwelled.

Lauren O’ Hagan, PhD candidate in Language and Communication, Cardiff University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Patricia A. Alexander, University of Maryland and Lauren M. Singer, University of Maryland

Today’s students see themselves as digital natives, the first generation to grow up surrounded by technology like smartphones, tablets and e-readers.

Teachers, parents and policymakers certainly acknowledge the growing influence of technology and have responded in kind. We’ve seen more investment in classroom technologies, with students now equipped with school-issued iPads and access to e-textbooks. In 2009, California passed a law requiring that all college textbooks be available in electronic form by 2020; in 2011, Florida lawmakers passed legislation requiring public schools to convert their textbooks to digital versions.

Given this trend, teachers, students, parents and policymakers might assume that students’ familiarity and preference for technology translates into better learning outcomes. But we’ve found that’s not necessarily true.

As researchers in learning and text comprehension, our recent work has focused on the differences between reading print and digital media. While new forms of classroom technology like digital textbooks are more accessible and portable, it would be wrong to assume that students will automatically be better served by digital reading simply because they prefer it.

Our work has revealed a significant discrepancy. Students said they preferred and performed better when reading on screens. But their actual performance tended to suffer.

For example, from our review of research done since 1992, we found that students were able to better comprehend information in print for texts that were more than a page in length. This appears to be related to the disruptive effect that scrolling has on comprehension. We were also surprised to learn that few researchers tested different levels of comprehension or documented reading time in their studies of printed and digital texts.

To explore these patterns further, we conducted three studies that explored college students’ ability to comprehend information on paper and from screens.

Students first rated their medium preferences. After reading two passages, one online and one in print, these students then completed three tasks: Describe the main idea of the texts, list key points covered in the readings and provide any other relevant content they could recall. When they were done, we asked them to judge their comprehension performance.

Across the studies, the texts differed in length, and we collected varying data (e.g., reading time). Nonetheless, some key findings emerged that shed new light on the differences between reading printed and digital content:

Students overwhelming preferred to read digitally.

Reading was significantly faster online than in print.

Students judged their comprehension as better online than in print.

Paradoxically, overall comprehension was better for print versus

digital reading.

The medium didn’t matter for general questions (like understanding the main idea of the text).

But when it came to specific questions, comprehension was significantly better when participants read printed texts.

From these findings, there are some lessons that can be conveyed to policymakers, teachers, parents and students about print’s place in an increasingly digital world.

1. Consider the purpose

We all read for many reasons. Sometimes we’re looking for an answer to a very specific question. Other times, we want to browse a newspaper for today’s headlines.

As we’re about to pick up an article or text in a printed or digital format, we should keep in mind why we’re reading. There’s likely to be a difference in which medium works best for which purpose.

In other words, there’s no “one medium fits all” approach.

2. Analyze the task

One of the most consistent findings from our research is that, for some tasks, medium doesn’t seem to matter. If all students are being asked to do is to understand and remember the big idea or gist of what they’re reading, there’s no benefit in selecting one medium over another.

But when the reading assignment demands more engagement or deeper comprehension, students may be better off reading print. Teachers could make students aware that their ability to comprehend the assignment may be influenced by the medium they choose. This awareness could lessen the discrepancy we witnessed in students’ judgments of their performance vis-à-vis how they actually performed.

3. Slow it down

In our third experiment, we were able to create meaningful profiles of college students based on the way they read and comprehended from printed and digital texts.

Among those profiles, we found a select group of undergraduates who actually comprehended better when they moved from print to digital. What distinguished this atypical group was that they actually read slower when the text was on the computer than when it was in a book. In other words, they didn’t take the ease of engaging with the digital text for granted. Using this select group as a model, students could possibly be taught or directed to fight the tendency to glide through online texts.

4. Something that can’t be measured

There may be economic and environmental reasons to go paperless. But there’s clearly something important that would be lost with print’s demise.

In our academic lives, we have books and articles that we regularly return to. The dog-eared pages of these treasured readings contain lines of text etched with questions or reflections. It’s difficult to imagine a similar level of engagement with a digital text. There should probably always be a place for print in students’ academic lives – no matter how technologically savvy they become.

Of course, we realize that the march toward online reading will continue unabated. And we don’t want to downplay the many conveniences of online texts, which include breadth and speed of access.

![]() Rather, our goal is simply to remind today’s digital natives – and those who shape their educational experiences – that there are significant costs and consequences to discounting the printed word’s value for learning and academic development.

Rather, our goal is simply to remind today’s digital natives – and those who shape their educational experiences – that there are significant costs and consequences to discounting the printed word’s value for learning and academic development.

Patricia A. Alexander, Professor of Psychology, University of Maryland and Lauren M. Singer, Ph.D. Candidate in Educational Psychology, University of Maryland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at 5 tips for reading multiple books at the same time.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2017/09/24/tips-for-reading-multiple-books-at-the-same-time/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the transition from printed books to ebooks.

For more visit:

http://www.mydaytondailynews.com/news/opinion/from-print-books-sadly-but-inevitably/DutwSmb4iMXamcPLRoLPjO/

The question of when to get rid of a book (or books) is one that often causes a bibliophile many a heart palpitation. It may even seem bad form to even contemplate the question, let alone ask it in a blog (especially when the person doing the asking is a fellow bibliophile.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at this very question, with some worthwhile advice.

For more visit:

http://bookriot.com/2017/06/27/when-to-get-rid-of-books/

You must be logged in to post a comment.