Wolf of the Plains by Conn Iggulden

Wolf of the Plains by Conn Iggulden

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Category Archives: Book Review

Finished Reading: The Wahhabi Code – How the Saudis Spread Extremism Globally by Terence Ward

Finished Reading: Moby Dick by Herman Melville

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

My rating: 1 of 5 stars

I understand many believe this book to be a classic and rate it highly. However, in my opinion, it was an exercise in self-indulgent pedantry and tedium, that I foolishly battled through so that I could simply be satisfied with having got through the thing.

Finished Reading: Australian Prime Ministers by Michelle Grattan

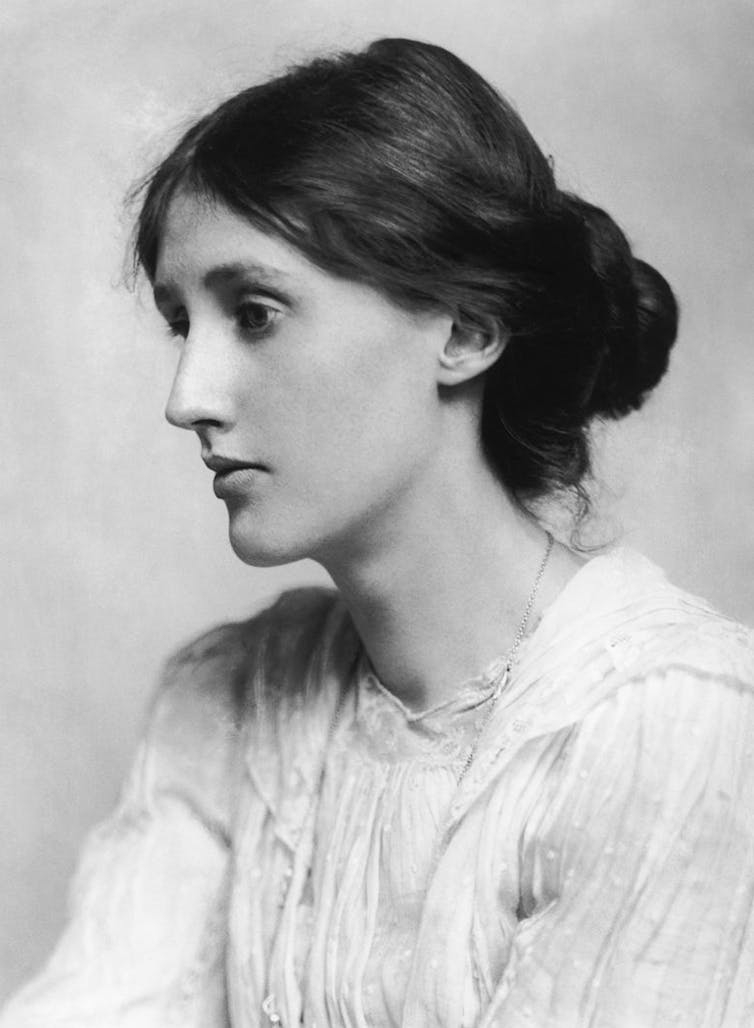

Guide to the classics: A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf’s feminist call to arms

Wikimedia Commons

Jessica Gildersleeve, University of Southern Queensland

I sit at my kitchen table to write this essay, as hundreds of thousands of women have done before me. It is not my own room, but such things are still a luxury for most women today. The table will do. I am fortunate I can make a living “by my wits,” as Virginia Woolf puts it in her famous feminist treatise, A Room of One’s Own (1929).

That living enabled me to buy not only the room, but the house in which I sit at this table. It also enables me to pay for safe, reliable childcare so I can have time to write.

It is as true today, therefore, as it was almost a century ago when Woolf wrote it, that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction” — indeed, write anything at all.

Still, Woolf’s argument, as powerful and influential as it was then — and continues to be — is limited by certain assumptions when considered from a contemporary feminist perspective.

Woolf’s book-length essay began as a series of lectures delivered to female students at the University of Cambridge in 1928. Its central feminist premise — that women writer’s voices have been silenced through history and they need to fight for economic equality to be fully heard — has become so culturally pervasive as to enter the popular lexicon.

Julia Gillard’s A Podcast of One’s Own, takes its lead from the essay, as does Anonymous Was a Woman, a prominent arts funding body based in New York.

Brendan Esposito

Even the Bechdel-Wallace test, measuring the success of a narrative according to whether it features at least two named women conversing about something other than a man, can be seen to descend from the “Chloe liked Olivia” section of Woolf’s book. In this section, the hypothetical characters of Chloe and Olivia share a laboratory, care for their children, and have conversations about their work, rather than about a man.

Woolf’s identification of women as a poorly paid underclass still holds relevance today, given the gender pay gap. As does her emphasis on the hierarchy of value placed on men’s writing compared to women’s (which has led to the establishment of awards such as the Stella Prize).

Read more:

Friday essay: science fiction’s women problem

Invisible women

In her book, Woolf surveys the history of literature, identifying a range of important and forgotten women writers, including novelists Jane Austen, George Eliot and the Brontes, and playwright Aphra Behn.

In doing so, she establishes a new model of literary heritage that acknowledges not only those women who succeeded, but those who were made invisible: either prevented from working due to their sex, or simply cast aside by the value systems of patriarchal culture.

To illustrate her point, she creates Judith, an imaginary sister of the playwright Shakespeare.

What if such a woman had shared her brother’s talents and was as adventurous, “as agog to see the world” as he was? Would she have had the freedom, support and confidence to write plays? Tragically, she argues, such a woman would likely have been silenced — ultimately choosing suicide over an unfulfilled life of domestic servitude and abuse.

In her short, passionate book, Woolf examines women’s letter writing, showing how it can illustrate women’s aptitude for writing, yet also the way in which women were cramped and suppressed by social expectations.

She also makes clear that the lack of an identifiable matrilineal literary heritage works to impede women’s ability to write.

Indeed, the establishment of those major women writers in the 18th and 19th centuries (George Eliot, the Brontes et al), when “the middle-class woman began to write” is, Woolf argues, a moment in history “of greater importance than the Crusades or the War of the Roses”.

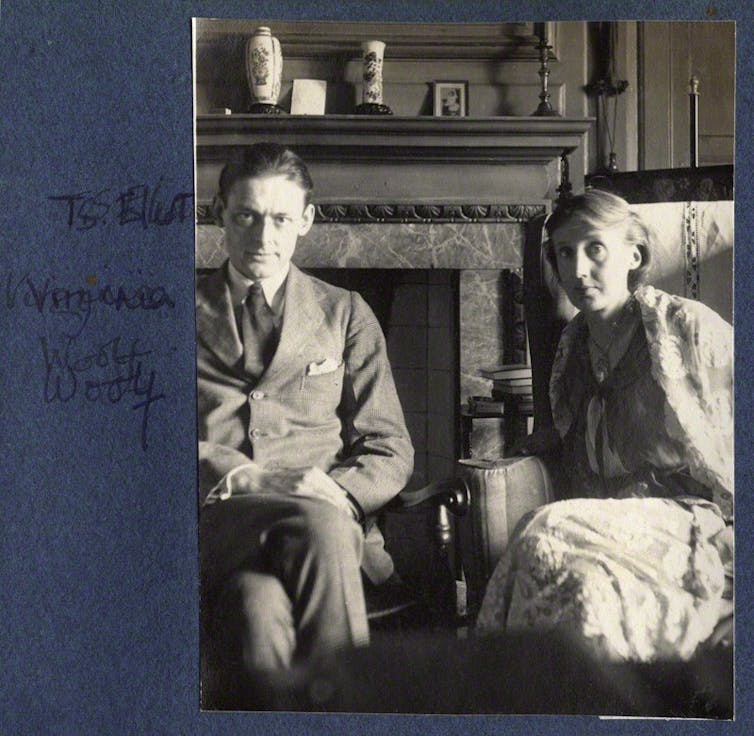

Male critics such as T.S. Eliot and Harold Bloom have identified a (male) writer’s relation to his precursors as necessary for his own literary production. But how, Woolf asks, is a woman to write if she has no model to look back on or respond to?

If we are women, she wrote, “we think back through our mothers”.

Wikimedia Commons

Read more:

#ThanksforTyping: the women behind famous male writers

Her argument inspired later feminist revisionist work of literary critics like Elaine Showalter, Sandra K. Gilbert and Susan Gubar who sought to restore the reputation of forgotten women writers and turn critical attention to women’s writing as a field worthy of dedicated study.

All too often in history, Woolf asserts, “Woman” is simply the object of the literary text — either the adored, voiceless beauty to whom the sonnet is dedicated or reflecting back the glow of man himself.

Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.

A Room of One’s Own returns that authority to both the woman writer and the imagined female reader whom she addresses.

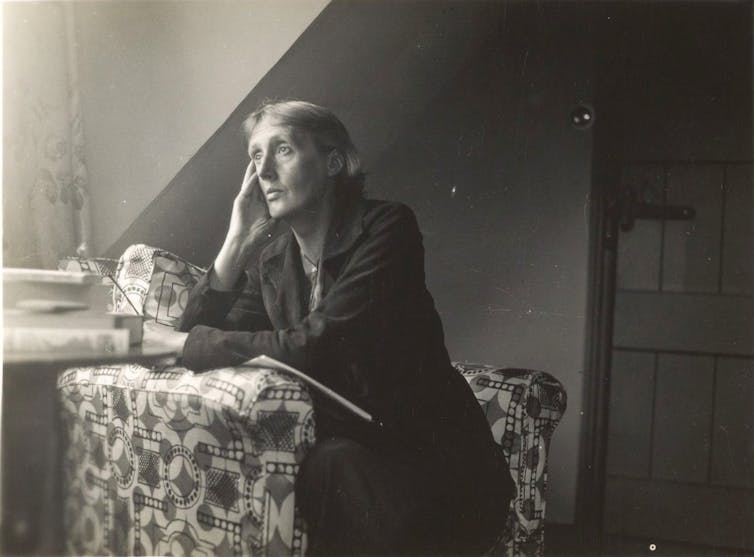

Stream of consciousness

Wikimedia Commons

A Room of One’s Own also demonstrates several aspects of Woolf’s modernism. The early sections demonstrate her virtuoso stream of consciousness technique. She ruminates on women’s position in, and relation to, fiction while wandering through the university campus, driving through country lanes, and dawdling over a leisurely, solo lunch.

Critically, she employs telling patriarchal interruptions to that flow of thought.

A beadle waves his arms in exasperation as she walks on a private patch of grass. A less-than-satisfactory dinner is served to the women’s college. A “deprecating, silvery, kindly gentleman” turns her away from the library. These interruptions show the frequent disruption to the work of a woman without a room.

This is the lesson also imparted in Woolf’s 1927 novel To the Lighthouse where artist Lily Briscoe must shed the overbearing influence of Mr and Mrs Ramsay, a couple who symbolise Victorian culture, if she is to “have her vision”. The flights and flow of modernist technique are not possible without the time and space to write and think for herself.

A Room of One’s Own has been crucial to the feminist movement and women’s literary studies. But it is not without problems. Woolf admits her good fortune in inheriting £500 a year from an aunt.

Indeed her purse now “breed(s) ten-shilling notes automatically”.

Wikimedia Commons

Part of the purpose of the essay is to encourage women to make their living through writing.

But Woolf seems to lack an awareness of her own privilege and how much harder it is for most women to fund their own artistic freedom. It is easy for her to advise against “doing work that one did not wish to do, and to do it like a slave, flattering and fawning”.

In her book, Woolf also criticises the “awkward break” in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847), in which Bronte’s own voice interrupts the narrator’s in a passionate protest against the treatment of women.

Here, Woolf shows little tolerance for emotion, which has historically often been dismissed as hysteria when it comes to women discussing politics.

A Room of One’s Own ends with an injunction to work for the coming of Shakespeare’s sister, that woman forgotten by history. “So to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worthwhile”.

Such a woman author must have her vision, even if her work will be “stored in attics” rather than publicly exhibited.

The room and the money are the ideal, we come to see, but even without them the woman writer must write, must think, in anticipation of a future for her daughter-artists to come.

An adaptation of A Room of One’s Own is currently at Sydney’s Belvoir Theatre.![]()

Jessica Gildersleeve, Associate Professor of English Literature, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

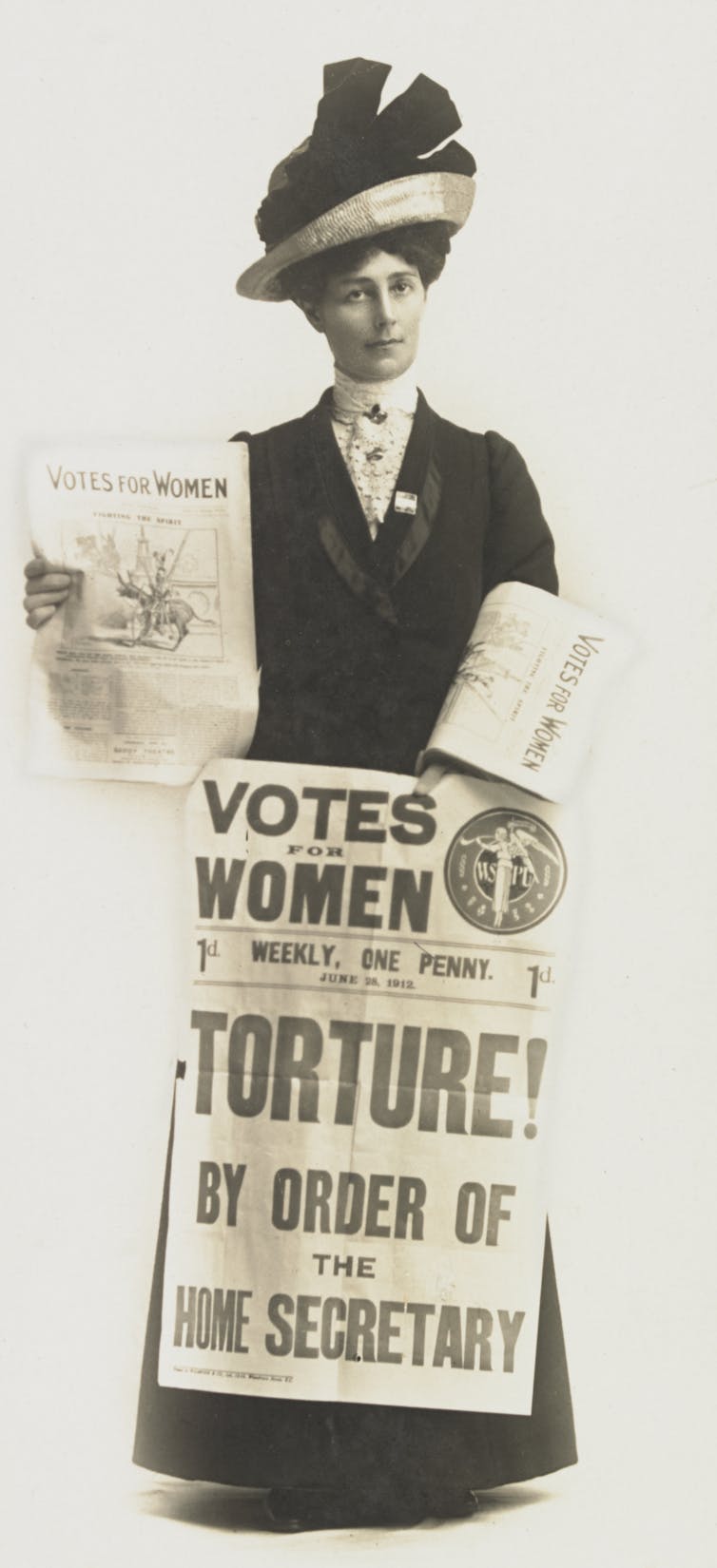

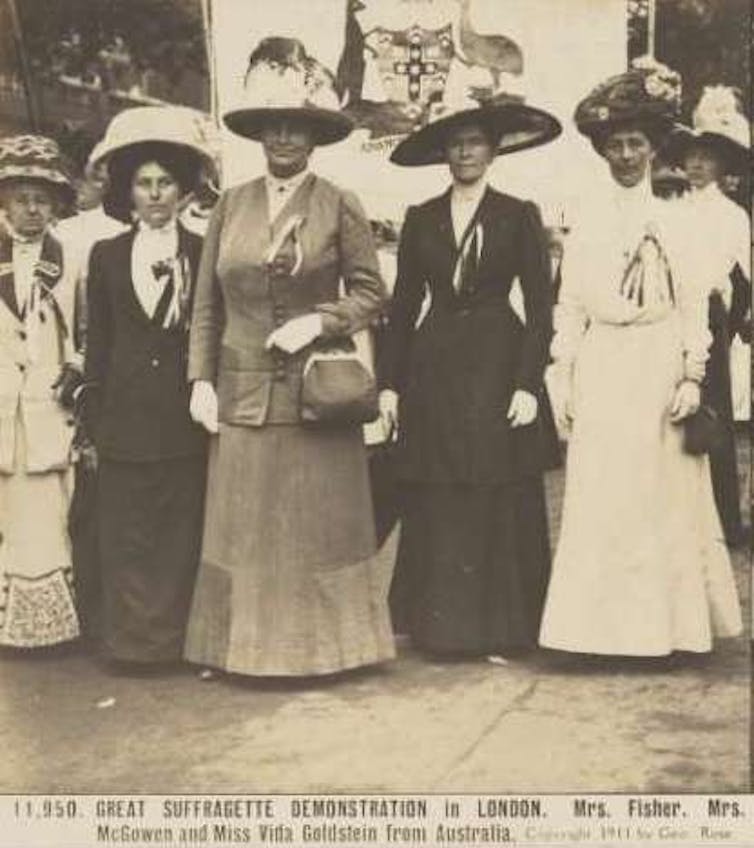

Review: new biography shows Vida Goldstein’s political campaigns were courageous, her losses prophetic

Marilyn Lake, University of Melbourne

Review: Vida: A Woman for Our Time, published by Penguin (Viking imprint)

Australian women were not the first to win the right to vote in national elections. That world-historic distinction belongs to New Zealanders. But they were the first to win, in 1902, both the right to vote and stand for election to the national parliament.

Three Australian women quickly availed themselves of the opportunity. Nellie Martel and Mary Bentley from New South Wales joined Vida Goldstein from Victoria as candidates in the 1903 federal election.

Little is now known of Martel and Bentley, but Goldstein’s contribution to politics has been commemorated in numerous scholarly studies, theses, essays, book chapters and encyclopedia entries, Janette Bomford’s biography That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman, and a federal electorate named in her honour. But historical memory is fickle and we need still to know more about the political history of women in Australia.

Read more:

Women’s votes: six amazing facts from around the world

Enlivened by speculation

A skilled and prize-winning biographer, Jacqueline Kent brings fresh enthusiasm and focus to her quest to understand Vida’s extraordinary political career and its disappointments in her new biography. Goldstein stood five times for election to the federal parliament and suffered five defeats.

Kent’s previous biography was The Making of Julia Gillard and it seems the painful experiences of our first woman Prime Minister – subject to relentless misogyny and sexist attacks – remain fresh in the writer’s mind.

Penguin

In Kent’s telling, Vida’s story is framed by Gillard’s fate. There are regular references to Gillard’s experiences and the trials of politicians such as Julie Bishop and Sarah Hanson-Young. Thus Vida’s biography becomes a story of continuity, rather than change, with Vida still “a woman for our time”.

Kent’s account is enlivened by speculation. Vida and her activist mother “might very well have attended” the initial meeting of the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society (VWSS) and “must have known about” the women’s novels then in circulation.

There is also a good amount of authorial displeasure evident. Women speakers had to endure “the tedious jocularity that was de rigueur” for mainstream journalists. The Age newspaper “evidently considered the welfare of women and children to be a trivial matter”.

Some of the most vivid passages in the book sketch the range of forceful personalities in the Melbourne “woman movement” of the late 19th century, who served as Vida’s models and mentors.

Henrietta Dugdale, cofounder of the VWSS was small in stature, but formidable in argument and the author of the radical Utopian novel A Few Hours in a Far-Off Age. Brettena Smyth, “an imposing speaker, being six feet tall and voluminous in figure, with blue shaded spectacles” was also a member of the VWWS, and sold women contraceptives. Annette Bear-Crawford and Constance Stone were cofounders of the Shilling Fund that made possible the Queen Victoria Hospital for Women.

Read more:

‘Expect sexism’: a gender politics expert reads Julia Gillard’s Women and Leadership

Missing chapters

The larger community of the Australian “woman movement” is largely absent from this account.

There are glimpses of Rose Scott and Louisa Lawson in Sydney and Catherine Spence in Adelaide, who could be frosty when confronted by Goldstein’s evident ambition.

In 1902, Goldstein represented “Australasian” women at the First International Woman Suffrage Conference in Washington, DC. Yet Spence, who preceded Goldstein in her informal role as ambassador for Australian women at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and embarked on a lecture tour, offered her successor a long list of contacts and helpful advice.

Scott, Spence, Goldstein and others of their generation were strong advocates of non-party politics for women, convinced they should avoid the male domination of established political parties. Their strong international connections reinforced woman-identified politics. But would enfranchised women vote as a bloc?

While in Boston in 1902, lecturing to a range of women’s groups, Goldstein met a bright young feminist, Maud Wood Park, whom she invited to Australia. When Goldstein hosted Park and her friend Myra Willard in Melbourne in 1909 she introduced them to future Labor Prime Minister Andrew Fisher and a number of Labor women at a tea party at Parliament House.

Elected to government in 1910, in a historic victory assisted by a strong women’s vote, Fisher responded to lobbying from Labor women and introduced the acclaimed Maternity Allowance.

Kent misses the significance of the rise of the labour women’s movement and its part in the 1910 election result.

Geo Rose/National Library of Australia

Questions of class

Class divisions mattered, but Kent tends to read Goldstein’s failure as a symptom of sexism, rather than class affiliation.

In the Epilogue, she observes that in the UK and US, Nancy Astor and Jeanette Rankin were quickly elected to Parliament and Congress. In Australia, Dorothy Tangney and Enid Lyons had to wait until 1943 to win seats in the Senate and House of Representatives. Kent doesn’t note, however, that Astor (Conservative) and Rankin (Republican) were party-endorsed candidates, as were Tangney (Labor) and Lyons (Liberal).

Sadly, Vida Goldstein’s series of electoral defeats as a non-party woman candidate would prove prophetic rather than path-breaking.

Goldstein’s courage and endurance qualify her as a woman for our time. But her political strategy of seeking power as an “independent woman candidate” meant she didn’t succeed then or set the most compelling example for aspiring political women today.

Read more:

More than a century on, the battle fought by Australia’s suffragists is yet to be won

![]()

Marilyn Lake, Professorial Fellow in History, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Finished Reading: The Substance of Civilization – Materials and Human History from the Stone Age to the Age of Silicon by Stephen L. Sass

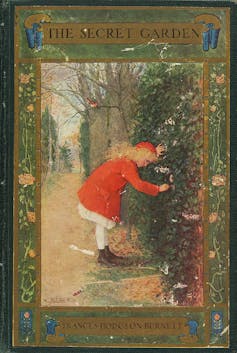

Guide to the Classics: The Secret Garden and the healing power of nature

StudioCanal

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden has been described as “the most significant children’s book of the 20th century.”

First published in 1911, after being serialised in The American Magazine, it was dismissed by one critic at the time as simple and lacking “plenty of excitement”. The novel is, in fact, a sensitive and complex story, which explores how a relationship with nature can foster our emotional and physical well-being. It also reveals anxieties about national identity at a time of the British Empire, drawing on ideas of Christian Science.

The Secret Garden has been read by generations, remains a fixture on children’s publishing lists today and has inspired several film versions. A new film, starring Colin Firth, Dixie Egerickx and Amir Wilson, updates the story in some ways for modern audiences.

Studiocanal

The book opens as nine-year-old Mary Lennox is discovered abandoned in an Indian bungalow following her parents’ deaths during a cholera outbreak. Burnett depicts India as a site of permissive behaviour, illness and lassitude:

[Mary’s] hair was yellow, and her face was yellow because she had been born in India and had always been ill in one way or another.

Mary is “disagreeable”, “contrary”, “selfish” and “cross”. She makes futile attempts at gardening, planting hibiscus blossoms into mounds of earth. The Ayah tasked with caring for Mary and the other “native servants … always obeyed Mary and gave her her own way in everything.”

On the death of her parents, Mary is sent to live with her reclusive uncle Archibald Craven at Misselthwaite Manor in Yorkshire.

Mary’s arrival in England proves a shock. The “blunt frankness” of the Yorkshire servants – in contrast to those in India – checks her behaviour. Martha Sowerby, an outspoken young housemaid, presents Mary with a skipping rope: Yorkshire good sense triumphing over Mary’s imperial malaise.

Also in the manor is Colin, her 10-year-old cousin. Hidden from Mary, she discovers him after hearing his cries at night.

Colin is unable to walk and believes he will not live to reach adulthood. Sequestered in his bedroom, Colin terrorises his servants with his tantrums: he performs “hysterics” in the model of Gothic femininity.

Transformation

Perhaps the most famous image associated with Burnett’s text is the locked door leading to the eponymous garden.

Houghton Library, Harvard University

This walled garden had formerly belonged to Colin’s mother, Lilias Craven. When she died after an accident in the garden, her husband, Archibald, locked the door and buried the key.

After Mary unearths the key, she begins to work in this mysterious, overgrown garden along with Martha’s brother, Dickon. Eventually, she manages to draw Colin out of his room with the help of Dickon, and the garden helps him to recover his strength.

Burnett draws upon the cultural connection between childhood and nature, highlighting Edwardian beliefs about the importance of the garden. Like other Edwardian texts, such as Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) and J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906), The Secret Garden also explores an English turn-of-the-century interest in paganism and the occult, expressed through the book’s fascination with the Greek god Pan.

Dickon, who shares an affinity with animals and the natural world, is first introduced as he sits under a tree “playing on a rough wooden pipe” reminiscent of Pan’s flute.

IMDB/Studiocanal

Mary and Colin are both physically and psychically transformed through working in the garden. The stifling rooms and constricting passages of Misselthwaite Manor are contrasted to the freedom of the secret garden.

At first it seemed that green things would never cease pushing their way through the earth, in the grass, in the beds, even in the crevices of the walls. Then the green things began to show buds and the buds began to unfurl and show colour, every shade of blue, every shade of purple, every tint and hue of crimson.

Read more:

B&Bs for birds and bees: transform your garden or balcony into a wildlife haven

The children are healed by gardening in the “fresh wind from the moor”. Both gain weight and strength and lose their pallor. Colin’s gardening suggests mastery of the space as he plants a rose – the floral emblem of England.

Mary is subordinated as Colin’s healing becomes the text’s main focus; Colin gains the ability to walk and – importantly – to win a race against her.

Warner Bros

‘Just mere thoughts’

The Secret Garden emphasises the power of positive thinking: “thoughts – just mere thoughts – are as powerful as electric batteries – as good for one as sunlight is, or as bad for one as poison”.

This focus on the power of positive thoughts highlights Burnett’s interest in New Thought and Christian Science. New Thought teaches that people can enhance their lives by altering their thought patterns. It was developed by Phineas Parkhurst Quimby in the 19th century, and one of Quimby’s students was Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science. While Burnett did not join either religion, she acknowledged that they influenced her work. Both religions often reject mainstream medicine.

Read more:

Why you should know about the New Thought movement

IMDB/MGM

Belief in the healing power of thoughts is reflected as Colin chants about the “magic” of the garden.

The sun is shining – the sun is shining. That is the Magic. The flowers are growing – the roots are stirring. That is the Magic. Being alive is the Magic – being strong is the Magic. The Magic is in me… It’s in every one of us.

The Secret Garden today

Written in a time of British imperial expansion, The Secret Garden’s anxieties around national identity are evident. It draws implicit (and explicit) distinctions between the sickliness and languor of India, and the health and vitality associated with life on the Yorkshire moors.

Yet The Secret Garden still resonates with contemporary audiences. This new adaptation elaborates upon the “magic” associated with the healing power of thoughts, introducing a fantastic element to the story as Mary, Colin and Dickon enter a secret garden filled with otherworldly plants.

Director Marc Munden’s new adaptation also appears to revisit the colonialist emphasis of Burnett’s text. The adaptation shifts the time period during which the film is set to 1947, the year of the Partition of India.

This temporal change suggests an alteration to the original text’s ideas about national identity. While Burnett’s 1911 text considered Britain’s relationship with India at the height of British imperialism, Munden’s adaptation situates the narrative in the period of India gaining independence from Britain.

This new film suggests a desire to ensure The Secret Garden’s continued relevance to today’s audiences, who may be attuned to the book’s colonialist ideologies.

The Secret Garden opens in select cinemas today.![]()

Emma Hayes, Academic, School of Communication and Creative Arts, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Not My Review: Burning the Books by Richard Ovenden

The links below are to book reviews of ‘Burning the Books,’ by Richard Ovenden.

For more visit:

– https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/sep/10/burning-the-books-by-richard-ovenden-review-knowledge-under-attack

– https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/aug/31/burning-the-books-by-richard-ovenden-review-the-libraries-we-have-lost

You must be logged in to post a comment.