The link below is to an article reporting on the winners of the 2021 Victorian Prize for Literature.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/02/02/162048/mckay-wins-100k-victorian-prize-for-literature/

The link below is to an article reporting on the winners of the 2021 Victorian Prize for Literature.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/02/02/162048/mckay-wins-100k-victorian-prize-for-literature/

Any social movement needs inspiration. It needs people who can imagine a different future and, more than that, make that future graspable.

Kate Jennings did that for the Australian women’s movement — with her incandescent anger, her sharp tongue and her courage, ready and able to speak straight into the face of power. Her death, in New York aged 72, offers a moment to reflect on the role of writers and literature as forces of social transformation.

many women are beginning to feel the necessity to speak for themselves, for their sisters.

i feel that necessity now.

When Jennings lined up for her turn to speak at a Vietnam moratorium rally on the lawns of Sydney University in 1970, she was a half-drop-out from Sydney’s English Department, living in Glebe.

With the group of determined women libbers at her back, she perhaps wasn’t clear what her speech would do — that it would effectively inaugurate second-wave feminism in Australia and help it become a movement with its own momentum. A new chapter for the world’s longest revolution. But she did know that the time had come.

When the speech appeared as a performative poem in her 2010 retrospective collection Trouble: Evolution of a Radical, she recalled that the group had conceived it as deliberately incendiary.

“Call the speech what you like — agitprop, political theatre, over the top, in your face — but we were genuinely angry, famously fed up. I wrote the speech at a boil: we were getting nowhere asking the men in the movement to listen to us.”

Written from within the mix of galvanising struggles then being fought around the world, the speech tore shreds off those for whom women’s issues were secondary or trivial. She compared the number of Australian men who’d died in Vietnam with the number of women who’d died from illegal abortions.

It was a shocking thing to do then: a similar comparison, now, of the victims of domestic violence to the number of Australian soldiers lost to recent conflicts or suicide, would be met with outrage too. The speech was hardline, uncompromising, militant.

okay i’ve stopped trying to understand my oppressor

i know who my enemy is

i will tell you what i feel, as an individual, as a woman

i feel that there can be no love between men and women

And that passion came from poetry. It wasn’t the theorists or social commentators who inspired the radical feminism powering the speech, she recalled, but the eloquence of visionaries.

In 2010, she listed Robin Morgan, Ti-Grace Atkinson, Valerie Solanas’s SCUM (Society for Cutting Up Men) Manifesto as her touchstones. This was writing that was “unafraid to be emotional, luminous with rage,” she recalled. “Manifestos and poems that jumped off the page. I loved it.”

Jennings’ other extraordinary contribution to the transformational feminism of the 1970s is one of its most revelatory — the huge, collaborative women’s poetry collection called Mother I’m Rooted, published in 1975.

Its confronting title is a distillation of the protest and exhaustion she saw in the poems. With Alison Lyssa, another poet and activist, she planned an anthology as inclusive as possible and advertised for poems — “trying to reach the women Out There”. Within two months they had over 500 replies.

The final volume lists 152 poets, including established ones, unknowns with new feminist pseudonyms, seasoned activists from the old left and many names that would go on to make their marks. It has experimental, Greek-Australian writers contesting the definition of poetry and forthright, white, working-class women writing about the washing — though no First Nations poetry.

It is a beautiful social document now, broken up by lambent photographs of ordinary women together. And its call for women’s control over not just what counted as poetry but over the publishing process itself was hugely influential, arguably changing the literary landscape in Australia forever.

Across her writing life, Jennings produced essays, novels, short stories and journalism, as well as poetry, all written with a fierce honesty and wit, refusing what she saw as cant and sentiment.

After she moved to New York in 1979, she continued to write about and for Australia, but often with an outsider’s cynicism. Women Falling Down in the Street, a collection of short stories from 1990, won a Queensland Premier’s Literary Prize and perhaps typified her interest in revisionary engagement with her part in Australia’s cultural life.

The novel Snake, from 1994, explored with concision and power her country childhood on a farm outside Griffith in NSW, and found an international readership.

In 2002, after her husband’s death from Alzheimer’s disease, she published Moral Hazard, a short but perfectly voiced novel about a writer making a living on Wall Street to support a dying partner. One of the few Australian novels to confront the operations of capital directly, even pre-empting the 2008 global collapse, it won a number of prizes, including the ALS Gold Medal.

The legacy she leaves is complex and multi-voiced, marked often by a reassessment of her younger self by the older Jennings and, perhaps, by a certain distrust of any shared story she couldn’t control.

But that legacy has been transformative and extraordinary, by any measure.![]()

Nicole Moore, Professor of English, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jodi McAlister, Deakin University

She published more than 70 novels and sold more than 34 million books translated into 29 languages, making her one of Australia’s most successful and prolific authors. Yet many are not familiar with her name.

Valerie Parv passed away suddenly last weekend, a week before her 70th birthday. She began as an advertising copywriter, and her first books, non-fiction home and garden DIY guides, were published in the late 1970s. In the 1980s, she began to publish in the genre she was most well-known for: romance fiction.

Her first romance novel, Love’s Greatest Gamble, was published by Harlequin Mills & Boon in 1982. This was, as Parv noted, a book which “broke a few moulds at the time”, featuring a widowed single mother heroine dealing with the fallout of her late husband’s PTSD-induced gambling addiction.

Parv went on to write 56 more romances across various Harlequin imprints. With these books, she was primarily working in the genre known as category romance — most frequently associated with Mills & Boon in Australia, and sold in print at discount department stores like Kmart, Big W and Target.

Romance fiction is often derided as formulaic. This is especially true for category romance fiction, as publisher guidelines can dictate things like length, setting and level of sexual content. Parv, however, firmly rejected this notion.

“All fiction has conventions but formula, hardly,” she wrote earlier this month.

“Not when people and their stories are so varied.”

In addition to writing romance, Parv also wrote science fiction novels and a number of non-fiction works. She is the only Australian recipient of the Romantic Times Book Reviews Pioneer award, which honours those who have broken new ground in the development of the romance novel.

Parv was unafraid to experiment, enjoining aspiring authors to “write dangerously” rather than to satisfy the market, and often hybridised genres in her work.

She frequently told an anecdote about her 1987 book The Leopard Tree, which raised the possibility its hero might have arrived by UFO.

While she received pushback on this from the English Harlequin imprint Mills & Boon, the book was published by the American imprint Silhouette, where the book, she would say, “became the poster-child for cutting edge romance for some years afterward”.

Completing her masters degree in 2007, Parv’s thesis was inspired by a question often posed to her by aspiring authors: “where do you get your ideas?”

Read more:

What’s next after Bridgerton? 5 romance series ripe for TV adaptation

She explored this question in relation to both her own work and the work of other authors, concluding authors often revisit themes and ideas resonant with their own lives, whether consciously or unconsciously.

In her own work, she observed a consistent preoccupation with characters resolving feelings of alienation, which she linked to the fact her family emigrated from Britain when she was seven, leaving her with a sense of rootlessness.

Parv’s professional career is as much a story of community-building as it is the story of an individual author.

An enormous part of her legacy will be her bestselling guides on the craft of writing, including The Art of Romance Writing (1993), Heart and Craft (2009), and, most recently, her part memoir/part writing advice volume 34 Million Books (2020), the title of which is a wink to her own prolific success.

In her writing guides, Parv focused unerringly on practical advice for writing, but also steered away from prescriptivism.

“There’s no one way to write a romance novel, no ‘secret’ that can be applied to every writer and every story,” she wrote in the introduction to Heart and Craft.

Parv was also strongly committed to mentorship. For 20 years, the Valerie Parv Award was run through the Romance Writers of Australia. Winners of the award — fondly referred to by Parv as her “minions” — received a year’s mentorship with Parv.

Nearly all of Parv’s minions have gone on to have works published. Their numbers include several highly successful romance authors, such as Kelly Hunter, Rachel Bailey and Bronwyn Parry.

In 2015, Parv was made a Member of the Order of Australia for significant contributions to the arts — both as a prolific author and as a mentor.

As a genre, romance fiction has never enjoyed an enormous amount of respect from outside its readership. For this reason, Parv — like her highly prolific and successful peer Emma Darcy, who predeceased her by four months — may never be a household name, despite her service to Australian literary culture: a fact of which she was well aware.

Despite this, she never ceased to advocate for the genre in which she made her career, and in which she assisted so many others to do the same.

“I will never send up romance in any form, because I believe in romance,” she commented on the Secrets From The Green Room podcast one month before her death.

“I’ve been in love, and I know how important it is to my life, and how it is to most people’s lives.”

Read more:

How to learn about love from Mills & Boon novels

![]()

Jodi McAlister, Lecturer in Writing, Literature and Culture, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sharon Goldfeld, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute; Hannah Bryson, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and Jodie Smith, La Trobe University

Around one in three (36%) Australian children grow up in families experiencing adversity. These include families where parents are unemployed, in financial stress, have relationship difficulties or experience poor mental or physical health.

Our recent study found one in four Australian children experiencing adversity had language difficulties and around one in two had pre-reading difficulties.

Language difficulties can include having a limited vocabulary, struggling to make sentences and finding it hard to understand what is being said. Pre-reading difficulties can include struggling to recognise alphabet letters and difficulties identifying sounds that make up words.

Learning to read is one of the most important skills for children. How easily a child learns to read largely depends on both their early oral language and pre-reading skills. Difficulties in these areas make learning to read more challenging and can affect general academic performance.

International studies show children experiencing adversity are more likely to have language and pre-reading difficulties when they start school.

Language difficulties are usually identified using a standardised language assessment which compares an individual child’s language abilities to a general population of children of the same age.

Pre-reading difficulties are difficulties in the building blocks for learning to read. For example, by the age of five, most children can name at least ten letters and identify the first sound in simple words (e.g. “b” for “ball”).

Children who have not developed these skills by the time they start school are likely to require extra support in learning to read.

We examined the language, pre-reading and non-verbal skills (such as attention and flexible thinking) of 201 five-year-old children experiencing adversity in Victoria and Tasmania.

We defined language difficulties as children having language skills in the lowest 10% compared to a representative population of Australian 5-year-olds. By this definition, we would expect one in ten children to have language difficulties.

But our rates were more than double this — one in four (24.9%) of the children in our sample had language difficulties.

Pre-reading difficulties were even more common: 58.6% of children could not name the expected number of alphabet letters and 43.8% could not identify first sounds in words.

By comparison, an Australian population study of four year olds (children one year younger than in our study) found 21% could not name any alphabet letters.

Again, our rates were more than double this.

Interestingly, we didn’t find these differences for children’s non-verbal skills. This suggests language and pre-literacy skills are particularly vulnerable to adversity.

Read more:

1 in 5 kids start school with health or emotional difficulties that challenge their learning

There are several reasons that could explain this. Early speech and language skills develop through interactions children have with their parents. These interactions can be different in families experiencing adversity, due to challenges such as family stress and having fewer social supports.

Families experiencing adversity may also have fewer resources (including time and books) to invest in their children’s early language and learning.

It is really challenging for children starting school with language and pre-reading skills to catch up to their peers. They need to accelerate their learning to close the gap.

Put into context, if a child starts school six months behind their peers, they will need to make 18 months gain within a year to begin the next school year on par with their peers. This is not achievable for many children, even with extra support, and a tall order for many schools.

Early reading difficulties often continue throughout the primary school years and beyond. Sadly, we also know that the long-term impacts of language and pre-reading difficulties don’t just include poor reading skills, but problems which can carry into adulthood.

These can include struggling academically, difficulties gaining employment, antisocial behaviour and poor well-being.

These results should be concerning for us all. There are clear and extensive social costs that come with early language and pre-reading difficulties, including a higher burden on health and welfare costs and productivity losses.

These impacts are particularly worrying given the significant school disruptions experienced due to the COVID-19 lockdowns. School closures will have substantially reduced children’s access to additional support and learning opportunities, particularly for those experiencing adversity, further inhibiting opportunities to catch up.

Our best bet is to ensure as many children as possible start school with the language and pre-reading skills required to become competent early readers.

For example, ensuring all children have access to books at home has shown promise in supporting early language skills for children experiencing adversity.

We know which children are at greatest risk of struggling with their early language and pre-reading skills. We now need to embed this evidence into existing health and education services, and invest in supports for young children and families to address these unequal outcomes.![]()

Sharon Goldfeld, Director, Center for Community Child Health Royal Children’s Hospital; Professor, Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne; Theme Director Population Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute; Hannah Bryson, Postdoctoral Researcher, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and Jodie Smith, Research Fellow, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Marina Deller, Flinders University

Brittany Higgins has signed a book deal with Penguin Random House Australia. Not just any book — a memoir.

Higgins says her book will be a chance to tell “a firsthand account of what it was like surviving a media storm that turned into a movement”.

Memoir can help readers explore and understand trauma from a very personal perspective. Research suggests writing can be used to work through, or even heal from, trauma. It is a chance for a writer like Higgins,

who alleges she was raped in a senior minister’s office, to reclaim her story.

Here are four powerful Australian examples of women’s memoirs about trauma and abuse.

Sydney-based author, writer, and researcher Bri Lee witnessed justice and heartbreak while working as a judge’s associate in the Queensland District Court. Two years later, she took her own abuser to court.

Although the abuse occurred in childhood, Lee pursued a conviction for the perpetrator (a family friend) in young adulthood. In her 2018 book, she acknowledges that the longer the time between an incident and investigation, the more potential hurdles may arise; her journey for justice is far from straightforward.

Lee acknowledges this in the way she explores personal, public, and legal discourse surrounding abuse. She jumps back and forth in time, and weaves her story with others in the Australian legal system in a blend of journalistic and personal storytelling. This approach also acknowledges trauma can affect memory. Details can be unbearably clear, difficult to remember, or both.

Through poetic reflection, and searing critique, Lee carves a space for her story.

From age 12, Gemma Carey was groomed and abused by a man twice her age. In young adulthood, Carey discovers her mother knew about the abuse. When her mother dies, the enduring effects of this betrayal surface.

Family memoirs are often taboo; family memoir about child abuse and complicity even more so. Despite fraught themes, the Sydney-based author and academic writes with rigour and honesty. Her 2020 memoir asks us to examine social — and family — structures which allow these injustices.

Carey’s tone is dark but inquisitive. She speaks directly to readers, incorporating research, and unpicking the threads of trauma and grief.

Carey emphasises writing about abuse doesn’t always fit a mould. In an interview, she explains, “Writing trauma stories that will change societal narratives around abuse and victims involves showing the contradictions that exist in trauma and grief”.

In her book, she reflects on her younger self,

I was broken and trying to work out how to fix myself … no one had ever given me the tools… I had to figure it out on my own.

This rebuilding took time. At 12, Carey buried her experience, at 17 she successfully took the perpetrator to court, in adulthood, she wrote her memoir.

Read more:

Friday essay: why we need children’s life stories like I Am Greta

In The Anti-Cool Girl (2018), comedian and writer Rosie Waterland reveals a turbulent childhood; drug and alcohol-addicted parents, absent family, death and loss, poverty, mental health struggles, and sexual abuse experienced within the Australian foster care system.

Waterland writes unflinchingly. She tackles difficult subjects with intelligence and humour. Each chapter is addressed to herself: “You will be in rehab several times before you’re ten years old”, or “Your foster dad will stick his hands down his pants, and you will feel so, so lucky”. Like Carey, Waterland acknowledges trauma often manifests in ways which might seem “odd” or “unconventional” to others.

While comedic throughout, Waterland approaches her trauma with care and, understandably, anger. She later lamented that she was unable to name her abuser, due to fears of litigation.

The Anti-Cool Girl, blending humour and pain, remains a testament to Waterland’s endurance and survival.

Chloe Higgins’ sisters — Carlie and Lisa — died in a car accident when Higgins was 17. In her 2019 memoir Higgins — a Wollongong-based author and academic — asks us to consider the nature of ongoing grief and the way trauma stretches over different experiences.

Higgins’ grief influences her sexual experiences in often troubling ways — but the way she discusses it is revolutionary. She explores the weaponisation of sex, how it is a form of self-harm; sex and substance abuse, and the pleasures and pressures of sex work.

She jumps between stories of gentility (caring lovers, exploration, sex clients who felt more like friends) and horror stories featuring coercion and fear, threats, and sex without consent. Higgins examines her own experiences and links them to memory, identity, and control.

In her Author’s Note, Higgins reflects: “Publishing this book is about stepping out of my shame”.

These are not the only parts of me, but they are the parts I’ve chosen to focus on … Since that period of my life, I have begun to recover.

These books signal the importance of memoir as a platform where personal trauma stories are told, reclaimed, and witnessed. They are a valuable (and intimate) contribution to the conversation about trauma and sexual abuse in Australia.

Read more:

Inside the story: writing trauma in Cynthia Banham’s A Certain Light

![]()

Marina Deller, PhD Candidate, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the longlists for the 2021 Indie Book Awards.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/12/09/160690/indie-book-awards-2021-longlists-announced/

Lucy Montgomery, Curtin University

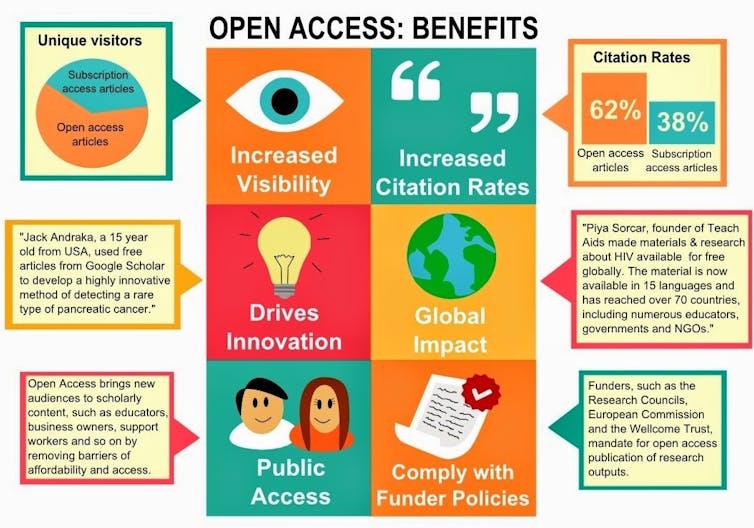

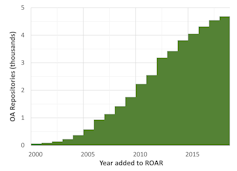

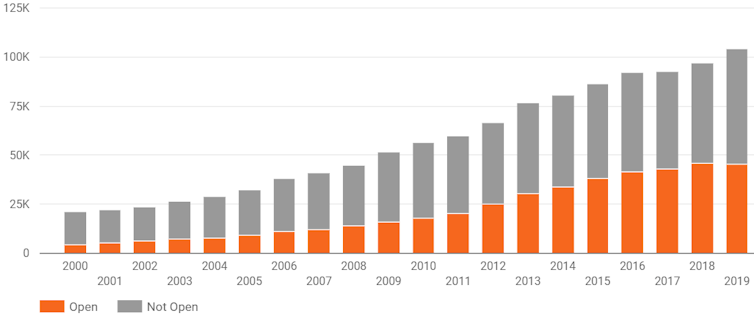

For all its faults, 2020 appears to have locked in momentum for the open access movement. But it is time to ask whether providing free access to published research is enough – and whether equitable access to not just reading but also making knowledge should be the global goal.

In Australia the first challenge is to overcome the apathy about open access issues. The term “open access” has been too easy to ignore. Many consider it a low priority compared to achievements in research, obtaining grant funding, or university rankings glory.

But if you have a child with a rare disease and want access to the latest research on that condition, you get it. If you want to see new solutions to climate change identified and implemented, you get it. If you have ever searched for information and run into a paywall requiring you to pay more than your wallet holds to read a single journal article that you might not even find useful, you will get it. And if you are watching dire international headlines and want to see a rapid solution to the pandemic, you will probably get it.

Many publishing houses temporarily threw open their paywall doors during the year. Suddenly, there was free access to research papers and data for scholars researching pandemic-related issues, and also for students seeking to pursue their studies online across a range of disciplines.

In October 2020, UNESCO made the case for open access to enhance research and information on COIVD-19. It also joined the World Health Organisation and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in calling for open science to be implemented at all stages of the scientific process by all member states.

There is clearly an appetite for freely available information. Since it was established earlier this year, the CORD-19 website has built up a repository of more than 280,000 articles related to COVID-19. These have attracted tens of millions of views.

Europe was already ahead of the curve on open access and 2020 has accelerated the change. Plan S is an initiative for open access launched in Europe in 2018. It requires all projects funded by the European Commission and the European Research Council to be published open access.

Read more:

All publicly funded research could soon be free for you, the taxpayer, to read

A 2018 report commissioned by the European Commission found the cost to Europeans of not having access to FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable) research data was €10 billion ($A16.1 billion) a year.

In 2019, open access publications accounted for 63% of publications in the UK, 61% in Sweden and 54% in France, compared to 43% of Australian publications.

Australia’s flagship Australian Research Council has required all research outputs to be open access since 2013. But researchers can choose not to publish open access if legal or contractual obligations require otherwise. This caveat has led to a relatively low rate of open access in Australia.

Read more:

Universities spend millions on accessing results of publicly funded research

The Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL) and the Australasian Open Access Strategy Group (AOASG) have long carried the torch for open access in Australia. But, without levers to drive change, they have struggled to change entrenched publishing practices of Australian academics.

Our Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative (COKI) project has examined open access across the world. We have analysed open access performance of individuals, individual institutions, groups of universities and nations in recent decades. The COKI Open Access Dashboard offers a glimpse into a subset of this international data, providing insights into national open access performance.

This analysis shows a steady global shift towards open access publications.

For example, in November 2020, Springer Nature announced it would allow authors to publish open access in Nature and associated journals at a price of up to €9,500 (A$15,300) per paper from January 2021. This was a signal change for the publishing industry. One of the world’s most prestigious journals is overturning decades of closed-access tradition to throw open the doors, and committing to increasing its open access publications over time.

At the moment, the pricing of this model enables only a select group to publish open access. The publication cost is equivalent to the value of some Australian research grants. Pricing is expected to become more affordable over time.

Read more:

Increasing open access publications serves publishers’ commercial interests

This international trend is a positive step for fans of freely available facts. However, we should not lose sight of other potentially larger issues at play in relation to open knowledge – that is, a level playing field for access to both published research and participation in research production.

Put another way, we need to pursue not only equity among knowledge takers but also among knowledge makers if we are to enable the world’s best thinkers to collaborate on the planet’s signature challenges.

All of this is good news for people who love to access information – but the bigger overall question for the higher education sector is about the conventions, traditions and trends that determine who gets to be considered for a job in a lab or a library or a lecture theatre. There is much more to be done to make our universities open for all – a future of equity in knowledge making as well as taking.![]()

Lucy Montgomery, Program Lead, Innovation in Knowledge Communication, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the shortlists for the 2021 Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/12/08/160636/victorian-premiers-literary-awards-2021-shortlists-announced/

The link below is to an article reporting on the winner of the Barbara Jefferis Award, Lucy Treloar for ‘Wolfe Island.’

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/11/19/159817/trelor-wins-2020-barbara-jefferis-award/

The link below is to an article reporting on the shortlist for the 2020 Voss Literary Prize.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/11/19/159827/voss-literary-prize-2020-shortlist-announced/

You must be logged in to post a comment.