The link below is to an article reporting on the winners of the 2020 Whiting Awards.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/03/26/35th-annual-whiting-award-winners/

The link below is to an article reporting on the winners of the 2020 Whiting Awards.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/03/26/35th-annual-whiting-award-winners/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at bookbinding.

For more visit:

https://blog.bookstellyouwhy.com/the-story-of-bookbinding

The link below is to an article that looks at selling rare books and who to turn to in order to do so.

For more visit:

https://blog.bookstellyouwhy.com/who-can-sell-my-rare-books

Paul Yachnin, McGill University

Shakespeare lived his life in plague-time. He was born in April 1564, a few months before an outbreak of bubonic plague swept across England and killed a quarter of the people in his hometown.

Death by plague was excruciating to suffer and ghastly to see. Ignorance about how disease spread could make plague seem like a punishment from an angry God or like the shattering of the whole world.

Plague laid waste to England and especially to the capital repeatedly during Shakespeare’s professional life — in 1592, again in 1603, and in 1606 and 1609.

Whenever deaths from the disease exceeded thirty per week, the London authorities closed the playhouses. Through the first decade of the new century, the playhouses must have been closed as often as they were open.

Epidemic disease was a feature of Shakespeare’s life. The plays he created often grew from an awareness about how precarious life can be in the face of contagion and social breakdown.

Except for Romeo and Juliet, plague is not in the action of Shakespeare’s plays, but it is everywhere in the language and in the ways the plays think about life. Olivia in Twelfth Night feels the burgeoning of love as if it were the onset of disease. “Even so quickly may one catch the plague,” she says.

In Romeo and Juliet, the letter about Juliet’s plan to pretend to have died does not reach Romeo because the messenger is forced into quarantine before he can complete his mission.

It is a fatal plot twist: Romeo kills himself in the tomb where his beloved lies seemingly dead. When Juliet wakes and finds Romeo dead, she kills herself too.

The darkest of the tragedies, King Lear, represents a sick world at the end of its days. “Thou art a boil,” Lear says to his daughter, Goneril, “A plague sore … In my corrupted blood.”

Those few characters left alive at the end, standing bereft in the midst of a shattered world, seem not unlike how many of us feel now in the face of the coronavirus pandemic.

It’s good to know that we — I mean all of us across time — might find ourselves sometimes in “deep mire, where there is no standing,” in “deep waters, where the floods overflow me,” in the words of the biblical psalmist.

But Shakespeare can also show us a better way. Following the 1609 plague, Shakespeare gave his audience a strange, beautiful restorative tragicomedy called Cymbeline. The international Cymbeline Anthropocene Project, led by Randall Martin at the University of New Brunswick, and including theatre companies from Australia to Kazakhstan, envisions the play as a way to consider how to restore a liveable world today.

Cymbeline took Shakespeare’s playgoers into a world without plague, but one filled with the dangers of infection nonetheless. The play’s evil queen experiments with poisons on cats and dogs. She even sets out to poison her stepdaughter, the princess Imogen.

Infection also takes the form of slander, which passes virus-like from mouth to mouth. The principal target again is Imogen, framed by wicked lies against her virtue by a man named Giacomo that her banished husband, Posthumus, hears. From Italy, Posthumus sends orders to his man in Britain to assassinate his wife.

The world of the play is also defiled by evil-eye magic, where seeing something abominable can sicken people. The good doctor Cornelius counsels the queen that experimenting with poisons will “make hard your heart.”

“… Seeing these effects will be

Both noisome and infectious.”

Even being seen by antagonistic people can be toxic. When Imogen is saying farewell to her husband, she is mindful of the threat of other people’s evil looking, saying:

“You must be gone,

And I shall here abide the hourly shot

Of angry eyes.”

Shakespeare leads us from this courtly wasteland toward the renewal of a healthy world. It is an arduous pilgrimage. Imogen flees the court and finds her way into the mountains of ancient Wales. King Arthur, the mythical founder of Britain, was believed to be Welsh, so Imogen is going back to nature and also to where her family bloodline and the nation itself began.

Indeed her brothers, stolen from court in early childhood, have been raised in the wilds of Wales. She reunites with them, though neither she nor they know yet that they are the lost British princes.

The play seems to be gathering toward a resolution at this juncture, but there is still a long journey. Imogen must first survive, so to speak, her own death and the death of her husband.

She swallows what she thinks is medicine, not knowing it’s poison from the queen. Her brothers find her lifeless body and lay her beside the headless corpse of the villain Cloten.

Thanks to the good doctor, who substituted a sleeping potion for the queen’s poison, Imogen doesn’t die. She wakes from a death-like sleep to find herself beside what she thinks is the body of her husband.

Yet, with nothing to live for, Imogen still goes on living. Her embrace of bare life itself is the ground of wisdom and the step she must take to reach toward her own and others’ happiness.

She comes at last to a gathering of all the characters. Giacomo confesses how he lied about her. A parade of truth-telling cleanses the world of slander. Posthumus, who believes that Imogen has been killed on his order, confesses and begs for death. She, in disguise, runs to embrace him, but in his despair he strikes her down. It is as if she must die again. When she recovers consciousness, and it’s clear she will survive, and they are reunited, Imogen says:

“Why did you throw your wedded lady from you?

Think that you are upon a rock, and now

Throw me again.”

Posthumus replies:

“Hang there like fruit, my soul,

Till the tree die.”

Imogen and Posthumus have learned that we come together in love only when the roots of our being grow deep into the natural world and only when we gain a full awareness that, in the course of time, we will die.

With that knowledge and in a world cured of poison, slander and the evil eye, the characters are free to look at each other eye to eye. The king himself directs out attention to how Imogen sees and is seen, saying:

“See,

Posthumus anchors upon Imogen,

And she, like harmless lightning, throws her eye

On him, her brothers, me, her master, hitting

Each object with a joy.”

We will continue to need good doctors now to protect us from harm. But we can also follow Imogen through how the experience of total loss can purge our fears, and learn with her how to start the journey back toward a healthy world.![]()

Paul Yachnin, Tomlinson Professor of Shakespeare Studies, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bart Beaty, University of Calgary

Last week, the producers behind a number of comic book-derived movies and TV shows announced delays for their franchises: release dates for Wonder Woman and Black Widow were pushed ahead, while The Walking Dead announced that COVID-19 had made it impossible for the show to complete work on the current season and that the finale was being delayed.

But what of the comic books that spawned these blockbuster franchises?

On March 23, Steve Geppi, CEO of Diamond Comic Distributors, announced the closing of the distribution system that holds a near-monopoly on the circulation of comic books in North America. He cited a number of problems related to the COVID-19 pandemic: comic retailers can’t service customers, publishing partners are having supply chain issues and shipping is delayed. He wrote his “only logical conclusion is to cease the distribution of new weekly product until there is greater clarity on the progress made toward stemming the spread of this disease.”

New Comics Day has occurred every Wednesday since the creation of the direct market in the 1970s, as die-hard fans rush to buy new books before spoilers pop up online.

But no longer: This week, for the first time in more than 80 years, no new comic books will ship to shops, and production is on hold into the foreseeable future. No previous global event — not the Second World War, not 9/11 — has previously shuttered the comic book industry.

To understand how this single decision could transform the operations of comic book publishers owned by Disney (Marvel Comics) and AT&T (DC Comics), among dozens of others, as well as comic production, consumption and culture, one needs to understand how the status of the comic book has shifted over the past century.

As Jean-Paul Gabilliet, professor of North American studies at Université Bordeaux demonstrates, the comic book form emerged in the 1930s as a promotional giveaway for department stores and gas stations before it migrated to the newsstand as a part of the larger magazine industry.

Despite some fits and starts, the format took off based the success of Superman, created in spring 1938, and the many imitation superheroes his popularity spawned as comic books became a staple of the newsstand. Circulation grew during the war, and exploded shortly after as new publishers initiated new genres like crime, romance and horror comic books.

By 1952, the peak year for comic book sales in the United States, comic books were a formidable cultural presence. But the rise of television, changes to the magazine distribution system and criticisms of the industry by public figures led to an industry-wide collapse of sales. Comic books limped through the 1960s as a cheap disposable form of entertainment for children, found on magazine racks that catered to parents.

By the 1970s, the American comic book had lost its status as a mass medium. At the same time, a rapidly growing network of used comic-book dealers began to spring up at flea markets, conventions, bookstores and eventually specialty stores that catered to a devoted set of comic collectors. The growing fan network presented a life raft to the industry.

The turning point, as American writer and reporter Dan Gearino points out in his history of comic book stores, came in 1972 when a convention organizer named Phil Seuling convinced the major publishers to wholesale new issues to him on a non-returnable basis.

This appealed to the publishers, who were accustomed to routinely over-printing comic books by the hundreds of thousands to supply the inefficient system of mom-and-pop corner stores that retailed their work. Seuling’s model shifted risk from the publisher to the retailer, who ordered product on a non-returnable basis, but it facilitated the growth of a network of thousands of comic book shops across North America.

For more than two decades, comic book shops were supplied by a network of regional wholesale distributors that served specific geographic regions based on the location of their warehouses. This changed at the end of 1994 when Marvel Comics bought Heroes World, the third largest distributor.

American writer Sean Howe’s history of Marvel Comics details how, in July 1995, the company made their new subsidiary the exclusive supplier of their market-leading product, reducing income at the other distributors by a third. A scramble ensued, with Geppi’s Diamond securing the rights to DC Comics and Image Comics, the next two largest publishers after Marvel. Other publishers quickly fell in line, signing exclusive deals with Diamond and bankrupting the regional distributors.

When Heroes World proved incapable of supporting Marvel’s needs, the company folded in 1996 and Marvel joined forces with Diamond, the only other distributor still standing. That same year, the Bill Clinton government began investigating Diamond as a monopoly. But the government dismissed the case in 2000, finding that the new company was not monopolistic because comic books were only a small part of the overall publishing industry.

The situation remained largely unchanged for more than 20 years. Diamond is the exclusive dealer of comic books to the a network of thousands of comic book stores who have continued to order on a non-returnable basis. Until now.

The consequences of Diamond’s decision are immediate and wide-reaching. In closing their warehouses to new product, publishers have alerted printers to stop. Comic book freelancers recently began tweeting they’d received “pencils down” messages from publishers curtailing production.

Communication to comic book retailers, creative personnel and fans has been haphazard as the large publishers scramble to plan for an uncertain future. Many are concerned about the growing digital footprint of comic book publishers.

Since 2011, most comic books have been released to comic book stores and in electronic format to consumers through platforms like Comixology (a subsidiary of Amazon) on the same day.

With a protracted closure of the distribution system, publishers like Marvel and DC could continue to move forward with electronic sales, which would inevitably bolster that end of their business at the expense of their retail partners. Archie Comics has announced that they will release some April titles digitally.

If several months passed with electronic sales but no physical comic book sales, it’s uncertain that those printed books would ever find an audience. An extended pause by the biggest publishers, on the other hand, would undoubtedly spur comics creators to pursue new projects either online or through the book trade.

This could accelerate a shift away from comic collectors’ habitual buying that take place comic shops as establishments that foster unique social relations, as described by Benjamin Woo, associate professor of communication and media studies at Carleton University.

While comic books sales proved remarkably resilient during the 2008 financial crisis, if the current situation breaks readers’ buying habits for a few months, they might never return in the same way.

This is a corrected version of a story originally published on March 30, 2020. The earlier story said Diamond Comic Distributors made an announcement March 24 instead of March 23.![]()

Bart Beaty, Professor of English, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dystopian fiction seems so alluring during the coronavirus pandemic. As we eagerly await a return to normalcy, many say we can aspire to do better — whether we are talking about wealth distribution or global warming. What dystopian fiction does especially well is to show how we can do more than simply repeat.

Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One (2018), an adaptation of Ernest Cline’s bestselling novel of the same title (2011), is a case in point. Set in 2045 in the city of Columbus, Ohio, it speaks of a world that has weathered corn syrup droughts and bandit riots.

People have now resorted to outliving rather than fixing the world’s problems. Accordingly, a virtual reality game known as the OASIS has become a refuge for many, including the central protagonist Wade Watts (Tye Sheridan).

Small wonder that the OASIS is so appealing. Within its walls, Spielberg pays homage to many aspects of popular culture. The video game Minecraft (2009) is a possible setting, and throughout the film, viewers watch Chucky, the Iron Giant and Mechagodzilla in battle.

Entire plot sequences incorporate existing popular characters, music and stories. In a nod to Superman, Watts dons Clark Kent glasses to conceal his identity. And in a sequence worthy of the film’s 2019 Academy Award nomination for Achievement in Visual Effects, Watts and his romantic interest Samantha Cook (Olivia Cooke) dance to the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” (1977).

The central conflict in Ready Player One arises when James Halliday (Mark Rylance), one of the OASIS’s creators, dies and leaves behind a seemingly impossible quest. The prize is his extensive fortune and total control over the OASIS. Watts’ competitors include the Innovative Online Industries (IOI), a loyalty centre that seeks to take over the OASIS.

The IOI is shown to be exploitative. Samantha’s father, we learn, borrowed gaming gear, built up debt and moved into the IOI in hopes to repay it, only to fall ill and die. Samantha stands to follow his example and her debt has already exceeded 23,000 credits.

What distinguishes the film — and its source material — is its exploration of how we negotiate with a social order rife with inequalities. This theme is particularly timely: COVID-19 has made apparent, for instance, the links between inequality and public health.

In the novel, the IOI’s corporate police arrest Wade, and he is marshalled out of his apartment complex and into a transport truck. As the vehicle moves, he peers out of its window and absorbs the changes that have befallen the world:

“A thick film of neglect still covered everything in sight …. The number of homeless people seemed to have increased drastically. Tents and cardboard shelters lined the streets, and the public parks I saw seemed to have been converted into refugee camps.”

The key term here is neglect. Wade is not alone in having forsaken the world. The virtual universe of the OASIS may have provided a convenient refuge. But choosing to escape the world’s realities has contributed to a dramatic rise in social and economic inequalities.

Both Cline’s novel and Spielberg’s film trace Watts’ growth into a better global citizen and his reconnection to the real world, so that his triumph can entail more than the regeneration of a flawed system. Spielberg expands on the novel by exploring what Watts does with his new-found wealth and power.

Watts shares his gains with his friends and together they take constructive steps towards improving both the OASIS and the wider world: they employ Halliday’s friend Ogden (Simon Pegg) as a non-exclusive consultant. They also ban loyalty centres from accessing the OASIS and switch off the virtual world on Tuesdays and Thursdays to encourage people to spend more time in the real world.

All of these actions seem commendable and they reveal how different Watts and his friends are to Halliday. Yet the film also exposes paradoxes inherent in fixing a broken system with its very tools.

In a recent article on the novel that I wrote with James Munday, a mathematics and statistics undergraduate student, we argue that any major change Wade makes to the OASIS, such as closing it for extended periods, demands that he and his fellow shareholders take on a substantial loss: their power is contingent upon the OASIS after all. But Wade seeks a more selfless and heroic win: creating a system that answers the needs of the many.

What Spielberg does especially well is to show the importance of imagining the world in new ways — and the temptation and problems with rebuilding a broken one in its own image.

In this, Spielberg harks back to a long genealogy of dystopian fiction, a genre invested in world building. The problems that Watts faces are anticipated, for instance, in George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), where we find an exploitative social system replaced by one even more so because it is more efficient.

Recently, Gregory Claeys provided us with an interdisciplinary map of the genre in his illuminating study Dystopia: A Natural History. In a short essay, he draws connections between the fears that we feel in these times of uncertainty to the genre’s central concerns.

As we collectively meditate on the world’s problems, why not imagine better worlds?![]()

Tom Ue, Adjunct Professor, Department of English, Dalhousie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

William Mitchell, Staffordshire University

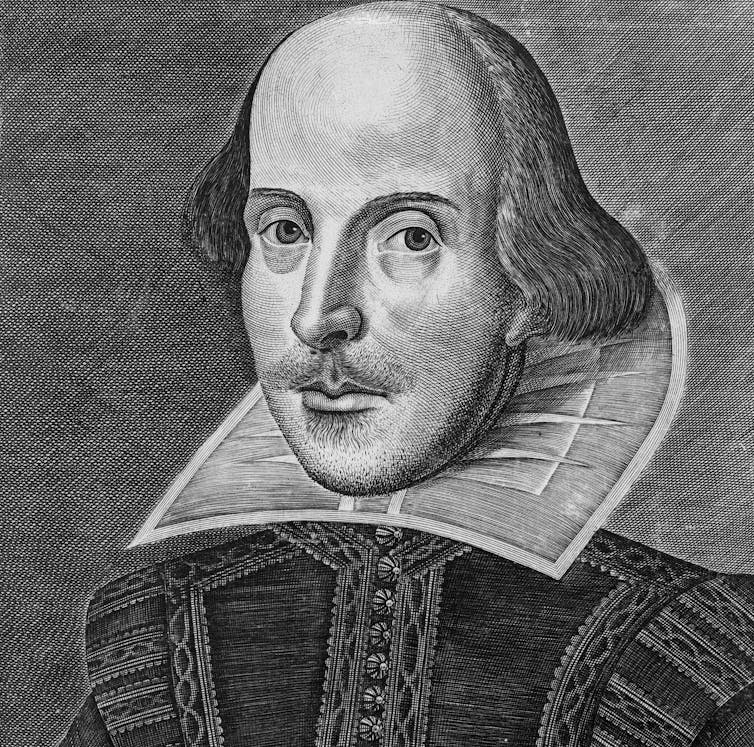

William Shakespeare is widely regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time and one of the most important and influential people who has ever lived. His written works (plays, sonnets and poems) have been translated into more than 100 languages and these are performed around the world.

There is also an enduring desire to learn more about the man himself. Countless books and articles have been written about Shakespeare’s life. These have been based primarily on the scholarly analysis of his works and the official record associated with him and his family. Shakespeare’s popularity and legacy endures, despite uncertainties in his life story and debate surrounding his authorship and identity.

The life and times of William Shakespeare and his family have also recently been informed by cutting-edge archaeological methods and interdisciplinary technologies at both New Place (his long-since demolished family home) and his burial place at Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. The evidence gathered from these investigations by the Centre of Archaeology at Staffordshire University provides new insights into his interests, attitudes and motivations – and those of his family – and shows how archaeology can provide further tangible evidence. These complement traditional Shakespearean research methods that have been limited to sparse documentary evidence and the study of his works.

Archaeology has the ability to provide a direct connection to an individual through the places and objects associated with them. Past excavations of the Shakespearean-era theatres in London have provided evidence of the places he worked and spent much of his time.

Attributing objects to Shakespeare is difficult, we have his written work of course, his portrait(s) and memorial bust – but all of his known possessions, like those mentioned in his will, no longer exist. A single gold signet ring, inscribed with the initials W S, is thought by some to be the most significant object owned and used by the poet, despite its questionable provenance.

Shakespeare’s greatest and most expensive possession was his house, New Place. Evidence, obtained through recent archaeological investigations of its foundations, give us quantifiable insights into Shakespeare’s thought processes, personal life and business success.

The building itself was lost in the 18th century, but the site and its remains were preserved beneath a garden. Erected in the centre of Stratford-upon-Avon more than a century prior to Shakespeare’s purchase in 1597, from its inception, it was architecturally striking. One of the largest domestic residences in Stratford, it was the only courtyard-style, open-hall house within the town.

This type of house typified the merchant and elite classes and in purchasing and renovating it to his own vision, Shakespeare inherited the traditions of his ancestors while embracing the latest fashions. The building materials used, its primary structure and later redevelopment can all be used as evidence of the deliberate and carefully considered choices made by him and his family.

Shakespeare focused on the outward appearance of the house, installing a long gallery and other fashionable architectural embellishments as was expected of a well-to-do, aspiring gentleman of the time. Many other medieval features were retained and the hall was likely retained as the showpiece of his home, a place to announce his prosperity, and his rise in status.

It provided a place for him and his immediate and extended family to live, work and entertain. But it was also a place which held local significance and symbolic associations. Intriguingly, its appearance also resembled the courtyard inn theatres of London and elsewhere with which Shakespeare was so familiar, presenting the opportunity to host private performances.

Extensive evidence of the personal possessions, diet and the leisure activities of Shakespeare, his family and the inhabitants of New Place were recovered during the archaeological investigations, revolutionising what we understand about his day-to-day life.

An online exhibition, due to be made available in early May 2020, presents 3D-scanned artefacts recovered at the site of New Place. These objects, some of which may have belonged to Shakespeare, have been chosen to characterise the chronological development and activities undertaken at the site.

Open access to these virtual objects will enable the dissemination of these important results and the potential for others to continue the research.

Archaeological evidence recovered from non-invasive investigations at Shakespeare’s burial place has also been used to provide further evidence of his personal and family belief. Multi-frequency Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) was used to investigate the Shakespeare family graves below the chancel of Holy Trinity Church.

A number of legends surrounded Shakespeare’s burial place. Among these were doubts over the presence of a grave, its contents, tales of grave robbing and suggestions of a large family crypt. The work confirmed that individual shallow graves exist beneath the tombstones and that the various members of Shakespeare’s family were not buried in coffins, but in simple shrouds. Analysis concluded that Shakespeare’s grave had been disturbed in the past and that it was likely that his skull had been removed, confirming recorded stories.

These family graves occupy a significant (and expensive) location in Holy Trinity Church. Despite this, the simple nature of Shakespeare’s grave, with no elite trappings or finery and no large family crypt, coupled with his belief that he should not be disturbed, confirm a simple regional practice based on pious religious observance and an affinity with his hometown.

Read more:

How to read Shakespeare for pleasure

There is still so much we don’t know about Shakespeare’s life, so it’s a safe bet that researchers will continue to investigate what evidence there is. Archaeological techniques can provide quantifiable information that isn’t available through traditional Shakespearean research. But just like other disciplines, interpretation – based on the evidence – will be key to unlocking the mysteries surrounding the life (and death) of the English language’s greatest writer.![]()

William Mitchell, Lecturer in Archaeology, Staffordshire University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Emma Smith, University of Oxford

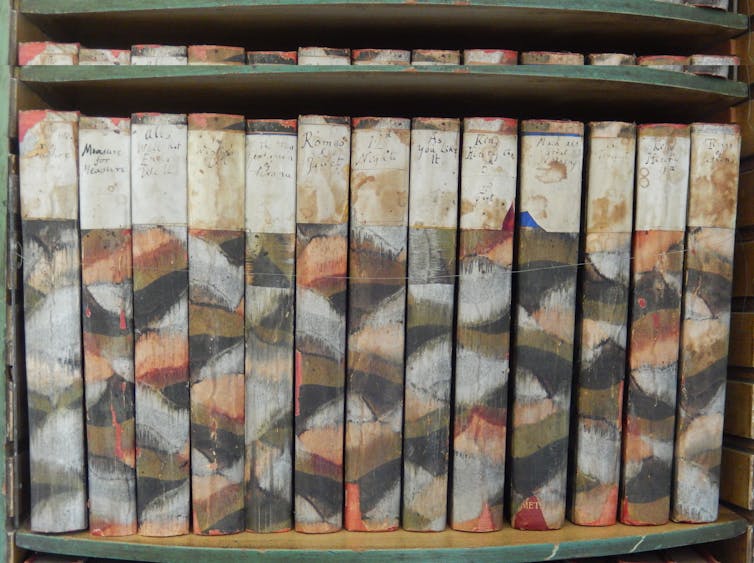

In recent years the orthodoxy that Shakespeare can only be truly appreciated on stage has become widespread. But, as with many of our habits and assumptions, lockdown gives us a chance to think differently. Now could be the time to dust off the old collected works, and read some Shakespeare, just as people have been doing for more than 400 years.

Many people have said they find reading Shakespeare a bit daunting, so here are five tips for how to make it simpler and more pleasurable.

If your edition has footnotes, pay no attention to them. They distract you from your reading and de-skill you, so that you begin to check everything even when you actually know what it means.

It’s useful to remember that nobody ever understood all this stuff – have a look at Macbeth’s knotty “If it were done when ‘tis done” speech in Act 1 Scene 7 for an example (and nobody ever spoke in these long, fancy speeches either – Macbeth’s speech is again a case in point). Footnotes are just the editor’s attempt to deny this.

Try to keep going and get the gist – and remember, when Shakespeare uses very long or esoteric words, or highly involved sentences, it’s often a deliberate sign that the character is trying to deceive himself or others (the psychotic jealousy of Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, for instance, expresses itself in unusual vocabulary and contorted syntax).

The layout of speeches on the page is like a kind of musical notation or choreography. Long speeches slow things down – and, if all the speeches end at the end of a complete line, that gives proceedings a stately, hierarchical feel – as if the characters are all giving speeches rather than interacting.

Short speeches quicken the pace and enmesh characters in relationships, particularly when they start to share lines (you can see this when one line is indented so it completes the half line above), a sign of real intimacy in Shakespeare’s soundscape.

Blank verse, the unrhymed ten-beat iambic pentamenter structure of the Shakespearean line, varies across his career. Early plays – the histories and comedies – tend to end each line with a piece of punctuation, so that the shape of the verse is audible. John of Gaunt’s famous speech from Richard II is a good example.

This royal throne of kings, this sceptered isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars.

Later plays – the tragedies and the romances – tend towards a more flexible form of blank verse, with the sense of the phrase often running over the line break. What tends to be significant is contrast, between and within the speech rhythms of scenes or characters (have a look at Henry IV Part 1 and you’ll see what I mean).

Shakespeare’s plays aren’t novels and – let’s face it – we’re not usually in much doubt about how things will work out. Reading for the plot, or reading from start to finish, isn’t necessarily the way to get the most out of the experience. Theatre performances are linear and in real time, but reading allows you the freedom to pace yourself, to flick back and forwards, to give some passages more attention and some less.

Shakespeare’s first readers probably did exactly this, zeroing in on the bits they liked best, or reading selectively for the passages that caught their eye or that they remembered from performance, and we should do the same. Look up where a famous quotation comes: “All the world’s a stage”, “To be or not to be”, “I was adored once too” – and read either side of that. Read the ending, look at one long speech or at a piece of dialogue – cherry pick.

One great liberation of reading Shakespeare for fun is just that: skip the bits that don’t work, or move on to another play. Nobody is going to set you an exam.

On the other hand, thinking about how these plays might work on stage can be engaging and creative for some readers. Shakespeare’s plays tended to have minimal stage directions, so most indications of action in modern editions of the plays have been added in by editors.

Most directors begin work on the play by throwing all these instructions away and working them out afresh by asking questions about what’s happening and why. Stage directions – whether original or editorial – are rarely descriptive, so adding in your chosen adverbs or adjectives to flesh out what’s happening on your paper stage can help clarify your interpretations of character and action.

One good tip is to try to remember characters who are not speaking. What’s happening on the faces of the other characters while Katherine delivers her long, controversial speech of apparent wifely subjugation at the end of The Taming of the Shrew?

The biggest obstacle to enjoying Shakespeare is that niggling sense that understanding the works is a kind of literary IQ test. But understanding Shakespeare means accepting his open-endedness and ambiguity. It’s not that there’s a right meaning hidden away as a reward for intelligence or tenacity – these plays prompt questions rather than supplying answers.

Would Macbeth have killed the king without the witches’ prophecy? Exactly – that’s the question the play wants us to debate, and it gives us evidence to argue on both sides. Was it right for the conspirators to assassinate Julius Caesar? Good question, the play says: I’ve been wondering that myself.

Returning to Shakespeare outside the dutiful contexts of the classroom and the theatre can liberate something you might not immediately associate with his works: pleasure.![]()

Emma Smith, Professor of Shakespeare Studies, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Michael via Flickr, CC BY-SA

David Brauner, University of Reading

For someone who teaches about the graphic novel, compiling an all-time top five list is challenging. It’s not just the way that such a list is compiled, making agonising decisions over which favourites to exclude, but also because it raises tricky questions of definition. That the term refers not just to fiction but to life-writing, as in all manner of memoirs, diaries and so on, is accepted – but beyond that there is little consensus.

If there are multiple volumes (as with Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman or the Hernandez brothers’ Love and Rockets series), should the whole series be counted as one epic graphic novel, or should only individual volumes be eligible?

And what about a book like Phoebe Gloeckner’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl(2002), which tells the story of an authorial alter-ego, Minnie, through a combination of prose diary entries, illustrations with captions, comic-strip narratives, letters, poems and photographs? Or Joe Sacco’s comic-strip documentary journalism?

I’ve chosen five books that I (and many others) regard as central to the graphic novel canon. They are all richly textured, powerful, nuanced books that are immediately arresting but also reward repeated re-reading.

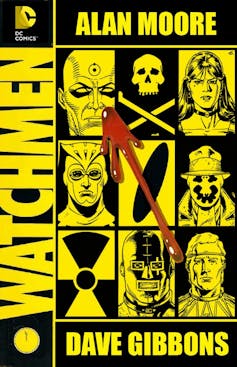

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen works on so many levels – it is, among other things, a whodunnit, a love story, a commentary on Cold War politics and an exploration of fundamental philosophical and ethical questions.

Watchmen is an homage to – and a deconstruction of – the classic superhero comic-strip narrative, which in turn has inspired numerous subsequent revisions of the genre, from Pixar’s The Incredibles (2004) to the Marvel Comics (and later MCU’s) Avengers civil war storyline.

Shifting points of view, disrupting chronology, layering texts within texts, Watchmen is a hugely ambitious narrative that discloses new details with every fresh reading. It’s also a real page-turner.

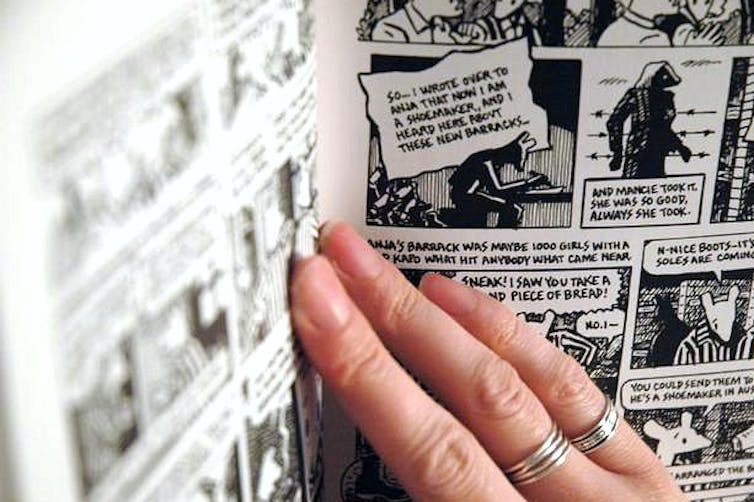

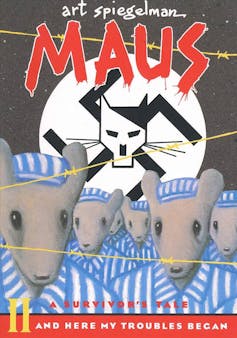

Art Spiegelman’s masterpiece, Maus, probably did more than any other graphic novel to make readers and critics take this genre seriously.

It’s the story of the author’s father, Vladek, who survived Auschwitz, as well as the story of Spiegelman’s relationship with him. Controversially representing Jews as anthropomorphised mice, preyed upon by German cat-people and often betrayed by Polish pig-people, Maus nevertheless resists stereotypes. The novel represents both its author and his father as flawed, complex individuals who struggle in different ways to deal with the legacy of a trauma that makes itself felt in every aspect of their lives.

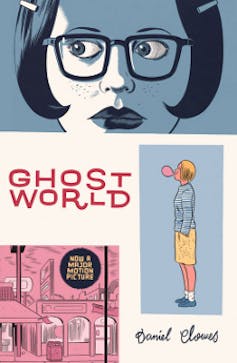

Daniel Clowes’ Ghost World is the shortest – and at first glance the most straightforward – of my choices. It’s a bittersweet tale of the friendship, and gradual estrangement, of recent high-school graduates Enid and Becky.

Cynical and vulnerable, with a sardonic sense of humour and a nostalgic streak, Enid is, in part, a portrait of the artist as a young girl grappling with her sexuality, ethnicity and her conflicting expectations of herself.

But Ghost World is also a powerful evocation of what it is like to drift, ghost-like, through a nondescript, soulless urban environment that is itself ghostly. Full of quirky characters and memorable images, Ghost World manages, paradoxically, to represent boredom and ennui vividly and entertainingly.

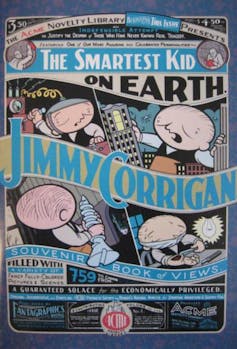

Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan was the first graphic novel to be awarded major literary prizes on both sides of the Atlantic – the American Book Award and The Guardian First Book Award.

Like Watchmen, Jimmy Corrigan has a complex, non-linear structure and subverts conventional notions of (super)heroism. Like Maus, it is a book about fathers and sons; and like Ghost World, it has a protagonist who is drifting aimlessly through life, alienated from the world around him.

Yet it is visually and formally more radical than any of the other books on this list. Chris Ware’s dark palette and landscape format and his use of diagrams, instructions and definitions make the book, as an object and text, highly unusual. In terms of narrative, too, Ware is a great innovator – the absence of exposition and page numbering, the abrupt transitions between a historical narrative focusing on Jimmy’s grandfather and the present-day narrative focusing on Jimmy, the use of surreal dream sequences and the disruption of conventional panel sequencing all make Jimmy Corrigan challenging.

But it’s well worth the effort. It is a beautiful, heartbreaking story that has been much imitated but never bettered.

Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home is a self-consciously literary coming of age novel that pays homage to James Joyce, Marcel Proust and Oscar Wilde, among others.

It is a moving memoir about the author’s relationship with her father, whose queer sexuality finds an echo in her lesbianism, and whose (possible) suicide haunts the book.

Adapted as an award-winning musical, Fun Home reached an audience that might never have encountered the bestselling graphic novel. Yet while Fun Home the musical is fun, just like the film adaptations of Watchmen and Ghost World, it can’t quite do justice to the complexity of the original.

Read more:

Guilty Pleasures: an English literature professor’s secret stash of graphic novels

What I hope a reading of these titles will demonstrate to any newcomers is that these are not just great graphic novels but great works of art. The term graphic novel was initially deployed in order to confer intellectual credibility on what had been previously seen as a trivial form of entertainment aimed primarily at children. But the works listed above rival anything done in the novel form over the same period – some of the most innovative and exciting work in fiction and life-writing is being done right now in the graphic novel form.![]()

David Brauner, Professor of Contemporary Literature, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Joshua Black, Australian National University

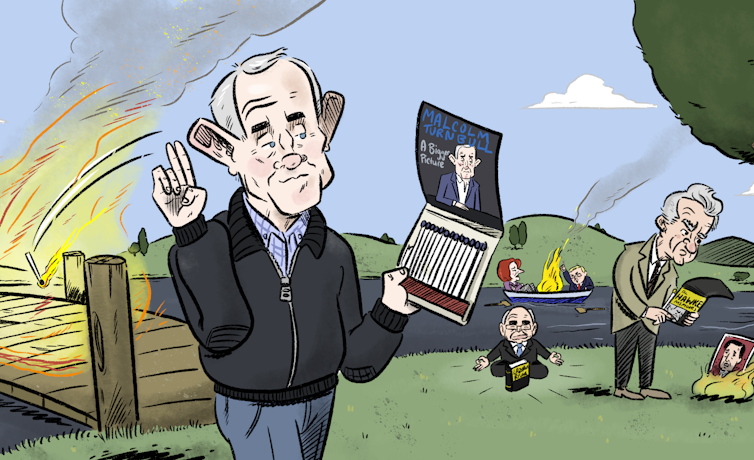

Landing in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, it may seem strange former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull’s memoir has generated so much political controversy.

Turnbull has been accused of hypocrisy and championing socialism, and has been threatened with expulsion from the Liberal Party.

In A Bigger Picture, Turnbull deals candidly with his antagonists inside the Coalition, who fought him bitterly on the same-sex marriage reform and climate policy. Similarly, he names and shames those he blames for the leadership insurgency of August 2018. All of this was expected, but none of it must please the current government.

But is the book any more inflammatory than previous prime ministerial memoirs?

Political controversy is a trademark of political memoir publishing in Australia. A Bigger Picture is just another page in that story.

Until the 1960s, prime ministerial memoirs were the exception, not the rule. Between 1945 and 1990, just three former prime ministers chose to publish books about their political lives. Two of them – Billy Hughes and Robert Menzies – produced two books each, and both political veterans sought to avoid “telling tales out of school”. Both seemed more interested in foreign affairs, particularly our imperial relationship to the UK in the case of Menzies.

The dismissal of the Whitlam government provoked both Sir John Kerr and Gough Whitlam to publish their memoirs. After reading extracts of Kerr’s Matters for Judgement, Whitlam decided to “set the record straight immediately” by writing The Truth of the Matter. His second book, The Whitlam Government, was also designed to make a political splash. Promising to explain the “development and implementation” of his policy program, the book was timed for release on the tenth anniversary of the dismissal itself, ensuring maximum publicity.

Since then, political controversy has accompanied prime ministerial memoirs, in part because incumbent political parties and leaders have had a vested interest in how these books might affect their popularity.

In his 1994 political memoir, Bob Hawke accused his rival and successor, Paul Keating, of calling Australia “the arse-end of the world” during an argument about the Labor leadership. Further, Hawke accused Keating of failing to support Australia’s involvement in the Gulf War against Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

Keating, who was attacked in parliament in October 1994 over the claims, called both allegations “lies”. Hawke offered to take a lie-detector test to prove his sincerity. Senior ALP figures recorded their outrage at Hawke’s memoir. But Hawke hit back, describing them as “precious self-appointed guardians of proper behaviour”.

Hawke’s predecessor also damaged his relationship with his own party in the process of publishing his memoirs. Malcolm Fraser’s Political Memoirs, written with journalist Margaret Simons, was recognised as one of Australia’s top ten books of 2010. His outspokenness – in the book and in his post-prime-ministerial life more generally – earned him many attacks from Coalition MPs.

John Howard handled the politics of his memoirs better than most politicians. Though the book was antagonistic toward his former treasurer, Peter Costello, Howard promised to “deal objectively” with events and relationships in Lazarus Rising. Ever the party stalwart, Howard and his publishers re-issued the book after the 2013 election with a new chapter that touted Tony Abbott’s “high intelligence, discipline […] good people skills”.

Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard both publicly took aim at one another in their memoirs, which made for plenty of media fodder. In My Story, Gillard described Rudd’s leadership as a descent into “paralysis and misery”. Rudd returned fire, calling her book her “latest contribution to Australian fiction”. However, he was unable to dent the book’s commercial success.

Four years later, Rudd in The PM Years accused Gillard of plotting “with the faceless men” to become prime minister. In a bid to patch over the historic rifts, he subsequently promised the Labor Party’s 2018 National Conference that the “time for healing” had come.

Critics of Turnbull’s book – such as Sky News’ Andrew Bolt and 2GB’s Ben Fordham – have argued that he and his publishers, Hardie Grant, were wrong to “betray confidences” and divulge “private conversations”.

In reality, political memoirs have always pushed against conventions of political secrecy. In the 1970s, British cabinet minister Richard Crossman published his Diaries, which included detailed descriptions of how cabinet functioned. The British establishment subsequently conducted the Radcliffe review into political memoirs and diaries. It found such material should be kept secret for 15 years, but that civil servants could do little to stop their political masters from publishing.

In 1999, Australia’s Neal Blewett was warned that publishing his A Cabinet Diary, recorded seven years earlier, could lead to prosecution under the Crimes Act because it revealed confidential cabinet discussions. Calling the public service’s bluff, Blewett published anyway. He explained in the book that “a few egos will be bruised, but cabinet ministers are a robust lot”. His diary shed significant light on the trials and tribulations of a ministerial life.

Since then, countless MPs and ministers have published books that claim to accurately represent personal conversations, some based on private notes (as Costello claimed in his memoirs), others on diary entries (as is the case in Turnbull’s book). In recent years, politicians have reproduced text messages and email exchanges in their books, as Bob Carr did in his 2014 book, Diary of a Foreign Minister. In each version of history, the author is the essential policymaker.

Read more:

View from The Hill: Malcolm Turnbull gives his very on-the-record account of Scott Morrison

In his book, Turnbull reveals private conversations and WhatsApp exchanges with colleagues, world leaders, public servants and more. His accounts of cabinet discussions are hardly ground-breaking: cabinet debates about the economy and national security under the Abbott government, for instance, were thoroughly detailed in Niki Savva’s The Road to Ruin, while the acrimonious debates about energy policy, same-sex marriage and home affairs inside the Turnbull government were laid bare in David Crowe’s Venom. Similarly, Turnbull’s criticisms of News Corporation’s biased reporting have been aired elsewhere, and stop short of Rudd’s argument in The PM Years that Rupert Murdoch should be the subject of a royal commission.

Turnbull’s book is another addition to the history of incendiary political memoir publishing in Australia. Political parties and their media associates have confirmed once again that a successful parliamentary memoir requires deft political management.

Ultimately, A Bigger Picture is not the compendium of revelations that some may perceive. Instead, it is another picture of politics in which “character” and “leadership” reign supreme at the expense of all other political forces.![]()

Joshua Black, PhD Candidate, School of History, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.