The link below is to an article that takes a look at the 2020 Stella Prize shortlist.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/03/06/147092/stella-prize-2020-shortlist-announced/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the 2020 Stella Prize shortlist.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/03/06/147092/stella-prize-2020-shortlist-announced/

The links below are to article reporting on the latest news and updates concerning Kindle apps and readers (the most recent are at the top).

For more visit:

– https://goodereader.com/blog/kindle/amazon-5-12-4-update-is-causing-trouble-on-some-kindle-e-readers

– https://blog.the-ebook-reader.com/2020/03/06/latest-kindle-update-issue-causing-homescreen-and-library-to-disappear/

– https://the-digital-reader.com/2020/02/25/kindle-ios-v6-28-adds-reading-ruler-feature-new-font-menu/

– https://blog.the-ebook-reader.com/2020/02/25/kindle-ios-update-6-28-adds-new-aa-menu-and-reading-ruler/

– https://the-digital-reader.com/2020/02/19/kindle-firmware-update-5-12-4-drops-hints-about-new-contrast-screensaver-features/

– https://blog.the-ebook-reader.com/2020/02/19/amazon-releases-new-software-update-5-12-4-for-kindles-big-changes-coming/

The link below is to an article that considers book collecting.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/02/10/toward-a-philosophy-on-book-collecting/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the 2020 Stella Prize longlist.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/02/07/145446/stella-prize-2020-longlist-announced/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at Alice Mayhew, who died recently.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/remembering-alice-mayhew-legendary-editor/

The links below are to articles reporting on that latest news (though a little late) on the Audible captions resolution (most recent are at the top).

For more visit:

– https://the-digital-reader.com/2020/02/09/amazon-is-extending-the-audible-caption-settlement-to-all-publishers-and-authors-will-you-disable-this-feature/

– https://the-digital-reader.com/2020/02/07/publishers-threw-the-public-under-the-bus-in-their-win-over-audible-captions/

– https://publishingperspectives.com/2020/02/copyright-coup-as-association-american-publishers-succeeds-in-audible-captions-case/

– https://goodereader.com/blog/audiobooks/audible-captions-now-has-a-resolution

Musée d’Orsay

Tom Stevenson, The University of Queensland

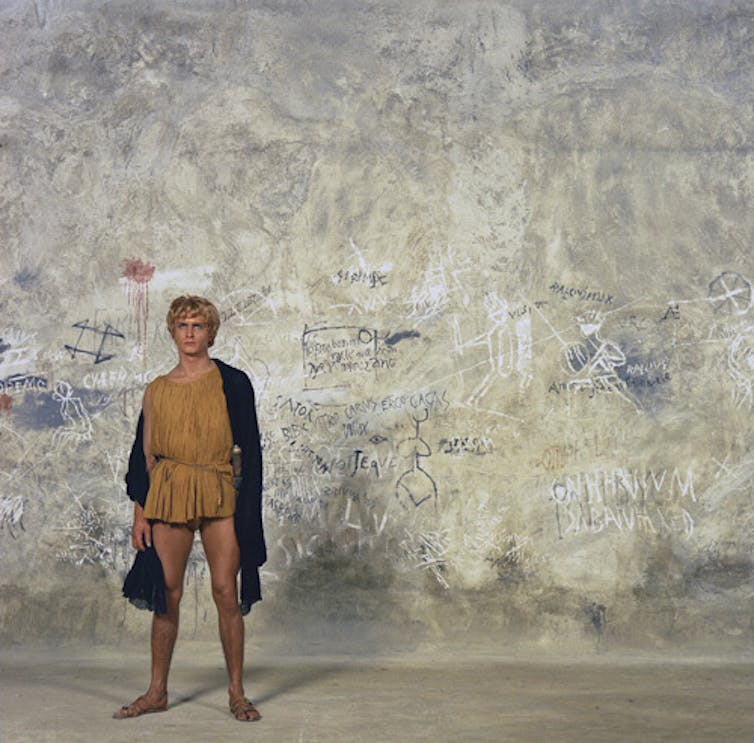

The Satyricon by Petronius is an unusual surviving text from the ancient world. It is not a work of history, nor a work of soaring epic poetry like Homer’s Iliad or Virgil’s Aeneid, and for various reasons it is hard to get a handle on.

Its contents are pretty grubby because it is about lowlifes and lowlife behaviour. It depicts petty theft, casual violence, opportunistic sex, prostitution, vulgar gluttony, crass displays of wealth by the most ridiculous social climber and gross disrespect for a range of gods, goddesses and hallowed religious rituals, like funerals and proper treatment of the dead. All the good sleazy stuff for when you’re in the mood for that sort of thing.

Rather than a work about heroes or kings or queens or uplifting examples of how to live a virtuous life, the Satyricon is almost a how-to manual for the opposite.

It is the earliest surviving novel in Latin literature, but it is not even close to being intact. We appear to have bits of three books out of an original 16 or possibly more. So we run into problems trying to understand what the plot of the whole work might have been and whether the bits that survive are representative of it.

As far as we can tell, it’s a tale about the misadventures and love triangle of three young men – the narrator Encolpius, Ascyltus and the younger Gitōn.

They all behave disreputably, all know hunger and poverty, all hurt people, and all get hurt in return.

Encolpius arguably suffers the most when he upsets Priapus, a god of fertility, who renders him impotent. Priapus is normally represented in Roman art sporting an enormous, erect phallus – even weighing it in one famous example. He is a minor deity in comparison to Jupiter or Hercules, but he has one outstanding trait, which means a great deal to the “heroes” of this novel.

When Priapus deprives Encolpius of his virility, he strikes at the core of Encolpius’s identity, causing him much distress and forcing him in panic to seek a succession of absurd remedies.

The main characters are not good boys. They are jealous, perpetually randy, violent, unfaithful and capricious. They separate and come back together. They lack depth. And they meet a series of characters who complement their deficiencies with flaws of their own.

They look for food, shelter, sex and sexual restoration. Charlatans abound. Everyone is selfish and untrustworthy. Religion is flouted and abused, even though it plainly has power.

The attitude to religion seems to be “whatever works”, but no one is exactly sure what works, so they indulge themselves in equal amounts of devotion and derision – with predictable results.

Read more:

Friday essay: the erotic art of Ancient Greece and Rome

Our youths seem to be travelling between locations around the Bay of Naples – a notorious region of excess and extravagance, heavily influenced by Greek culture and less constrained by traditional Roman discipline than other parts of Italy.

There is little certainty about this, as with so many features of the tale, but the easy movement between city dives and country villas makes sense in this region.

The most outrageous character they run across is the nouveau-riche pretender Trimalchio, whom they meet through an acquaintance, Eumolpus, who is said to be a poet but is more like a sleaze with intellectual pretensions.

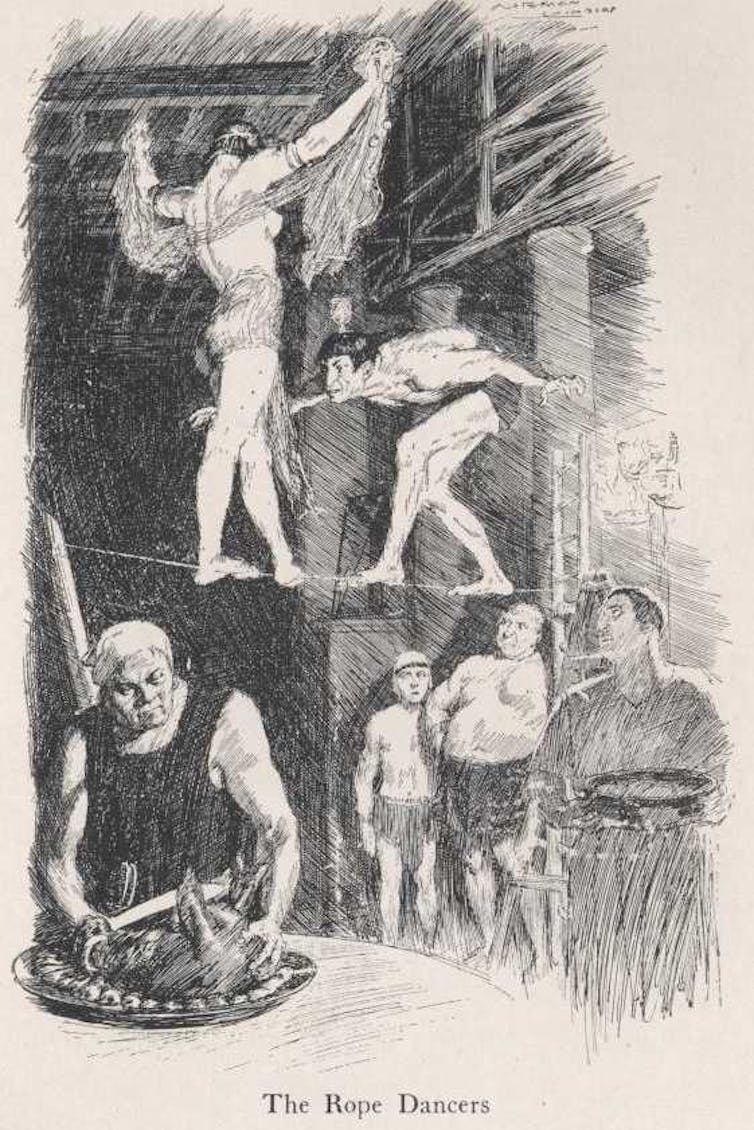

Together they end up at a sumptuous feast at Trimalchio’s villa – the famous Cena Trimalchionis or “Banquet of Trimalchio”.

The feast is a riot of nonsense. Trimalchio, an ex-slave who has bought his freedom, tries to prove he is a man of culture as well as wealth like his free-born counterparts in neighbouring villas and regions. In doing so, of course, he proves only that he completely lacks class or sophistication of any kind and emerges as a self-loving ignoramus.

There is way too much food, especially the meats and sweets. The dishes are too exotic and difficult, especially the tiny birds. They are served in ostentatiously absurd ways by a bizarre collection of slaves and other functionaries. The guests grab greedily and unappreciatively, upsetting plates, cups and each other. The talk is gross and unedifying.

Trimalchio ends up inviting his cronies to a rehearsal of his funeral, which he has planned meticulously on the model of a noble’s or emperor’s funeral. He fails to see how far he falls short. Clothes, and other props, do not make the man.

But there is more to the feast than meets the eye. The vulgarity of the subject matter is especially memorable because it is conveyed by a master satirist or comic genius.

Trimalchio is described with great attention to detail and inventiveness, and with a certain sympathy rather than vindictiveness. Trimalchio and his hangers-on are acquainted with high literature, though they mangle it terribly, sometimes speaking in vulgar Latin and in language rendered comic by its malapropisms and other features. The writer is a virtuoso for pulling off these effects so cleverly.

The key to interpretation is that the text is a satire, as its name implies. It is inspired by the deeds of satyrs: lecherous, half-human creatures of myth, obsessed with sex. They were symbols of the outrageous, the destabilising and the violent.

The youths of our tale are plainly modelled on them. And the text is comic in approach, designed for a festival atmosphere, when it’s okay to release the irrational, the absurd and the bottled-up frustrations that go along with daily commitment to civilised straightness.

The comic silliness of it all is important to consider when pondering the author and purpose of the work. The author, according to the name that has survived with the text, was Titus Petronius Arbiter.

He is generally identified with the prominent courtier of Nero, the senator Gaius Petronius, who was forced to commit suicide in AD 66 for his part in a conspiracy against the emperor. In a famous passage (Annals 16.17-20), Tacitus says Nero looked to this man as his “arbiter of elegance”, as though his judgment of culture and pleasure was admired.

Read more:

Mythbusting Ancient Rome – the emperor Nero

This identification between the author of the Satyricon and the Petronius of Tacitus might be right. Roman nobles were highly educated in literature and philosophy. Intellectual attainment was one of the myriad ways they competed with one another for social pre-eminence. Such a man might well have been capable of the literary virtuosity and wit that is on display in the text as we have it.

What is slightly worrying about this identification, however, is that Tacitus gives an appreciative portrayal of a man who sends up and resists a tyrant. Nero was certainly this, as the paranoia and murders of his reign indicate. Yet he was also a great sponsor of culture, especially literature and drama.

Even if the identifications with Tacitus’s Petronius and the reign of Nero are correct, we don’t need to adopt Tacitus’s tone and perspective. The Satyricon does not have to be a work with subversive intent against Nero, and Nero does not have to be read into the story in place of Trimalchio. Petronius does not have to be a social critic who was appalled by the corruption and depravity of Nero’s court.

It’s much more fun if he wasn’t any of these things in this work, but was instead a man who was excellent at satire in a spirit that was fundamentally light and frivolous.

Suggested translations: J.P. Sullivan, The Satyricon and the Fragments, translated with an introduction by J.P. Sullivan, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1965. P.G. Walsh, Petronius: The Satyricon, translated with an introduction and explanatory notes, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.![]()

Tom Stevenson, Associate Professor of Classics and Ancient History, UQ, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shutterstock

Peter Ellerton, The University of Queensland

The use of the word “I” in academic writing, that is writing in the first person, has a troublesome history. Some say it makes writing too subjective, others that it’s essential for accuracy.

This is reflected in how students, particularly in secondary schools, are trained to write. Teachers I work with are often surprised that I advocate, at times, invoking the first person in essays or other assessment in their subject areas.

In academic writing the role of the author is to explain their argument dispassionately and objectively. The author’s personal opinion in such endeavours is neither here nor there.

As noted in Strunk and White’s highly influential Elements of Style – (first published in 1959) the writer is encouraged to place themselves in the background.

Write in a way that draws the reader’s attention to the sense and substance of the writing, rather than to the mood and temper of the author.

This all seems very reasonable and scholarly. The move towards including the first person perspective, however, is becoming more acceptable in academia.

There are times when invoking the first person is more meaningful and even rigorous than not. I will give three categories in which first person academic writing is more effective than using the third person.

Above, I could have said “there are three categories” rather than “I will give three categories”. The former makes a claim of discovering some objective fact. The latter, a more intellectually honest and accountable approach, is me offering my interpretation.

I could also say “three categories are apparent”, but that is ignoring the fact it is apparent to me. It would be an attempt to grant too much objectivity to a position than it deserves.

In a similar vein, statements such as “it can be argued” or “it was decided”, using the passive voice, avoid responsibility. It is much better to say “I will argue that” or “we decided that” and then go on to prosecute the argument or justify the decision.

Taking responsibility for our stances and reasoning is important culturally as well as academically. In a participatory democracy, we are expected to be accountable for our ideas and choices. It is also a stand against the kinds of anonymous assertions that easily proliferate via fake and unnamed social media accounts.

Read more:

Post-truth politics and why the antidote isn’t simply ‘fact-checking’ and truth

It’s worth noting that Nature – arguably one of the world’s best science journals – prefers authors to selectively avoid the passive voice. Its writing guidelines note:

Nature journals prefer authors to write in the active voice (“we performed the experiment…”) as experience has shown that readers find concepts and results to be conveyed more clearly if written directly.

Some disciplines, such as anthropology, recognise that who is doing the research and why they are doing it ought to be overtly present in their presentation of it.

Removing the author’s presence can allow important cultural or other perspectives held by the author to remain unexamined. This can lead to the so-called crisis of representation, in which the interpretation of texts and other cultural artefacts is removed from any interpretive stance of the author.

This gives a false impression of objectivity. As the philosopher Thomas Nagel notes, there is no “view from nowhere”.

Philosophy commonly invokes the first person position, too. Rene Descartes famously inferred “I think therefore I am” (cogito ergo sum). But his use of the first person in Meditations on First Philosophy was not simply an account of his own introspection. It was also an invitation to the reader to think for themselves.

The third case is especially interesting in education.

I tell students of science, critical thinking and philosophy that a phrase guaranteed to raise my hackles is “I strongly believe …”. In terms of being rationally persuasive, this is not relevant unless they then go on tell me why they believe it. I want to know what and how they are thinking.

To make their thinking most clearly an object of my study, I need them to make themselves the subjects of their writing.

I prefer students to write something like “I am not convinced by Dawson’s argument because…” rather than “Dawson’s argument is opposed by DeVries, who says …”. I want to understand their thinking not just use the argument of DeVries.

Read more:

Thinking about thinking helps kids learn. How can we teach critical thinking?

Of course I would hope they do engage with DeVries, but then I’d want them to say which argument they find more convincing and what their own reasons were for being convinced.

Just stating Devries’ objection is good analysis, but we also need students to evaluate and justify, and it is here that the first person position is most useful.

It is not always accurate to say a piece is written in the first or third person. There are reasons to invoke the first person position at times and reasons not to. An essay in which it is used once should not mean we think of the whole essay as from the first person perspective.

We need to be more nuanced about how we approach this issue and appreciate when authors should “place themselves in the background” and when their voice matters.![]()

Peter Ellerton, Lecturer in Critical Thinking; Curriculum Director, UQ Critical Thinking Project, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Cassandra Pybus, University of Tasmania

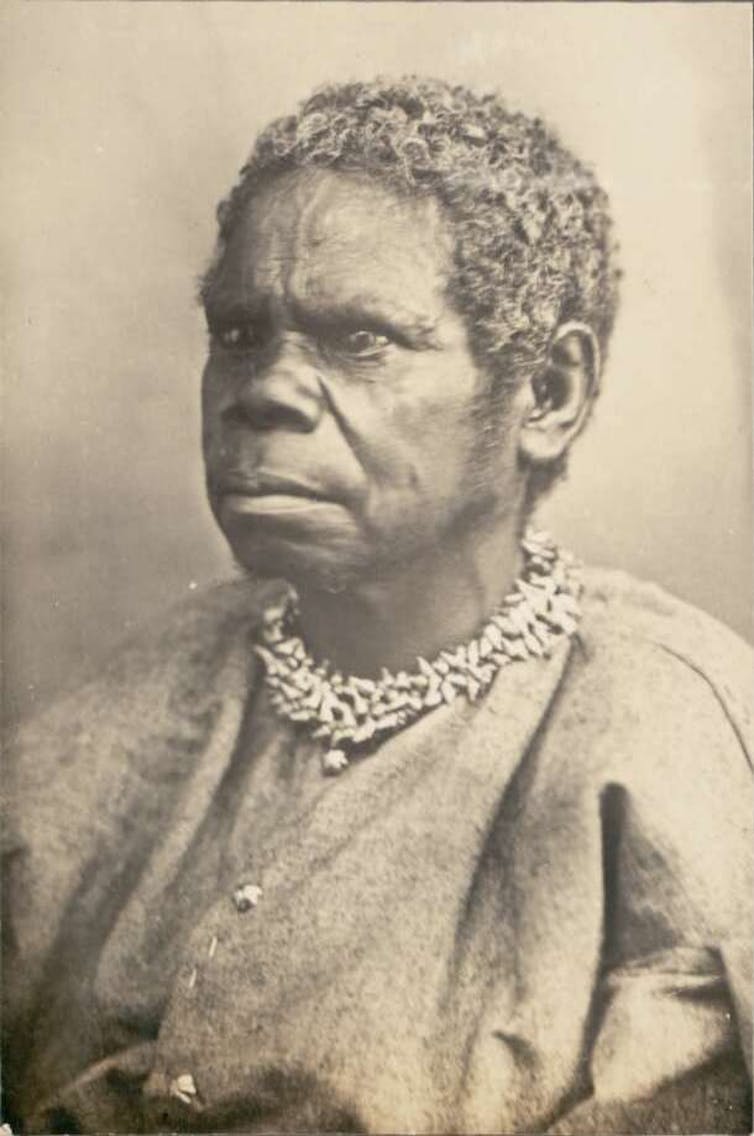

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

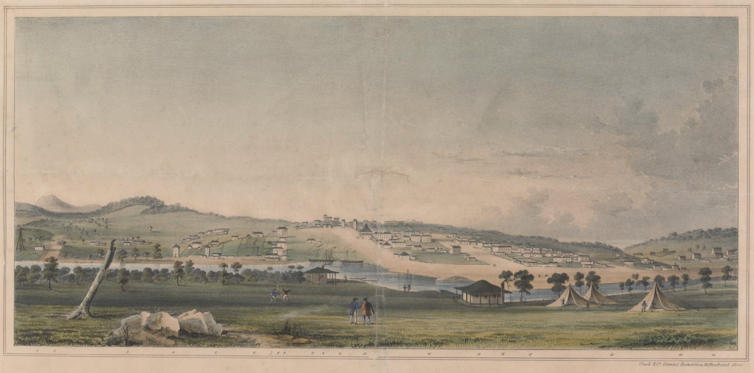

In 1839, George Augustus Robinson arrived in Melbourne as Chief Protector of Aborigines for the Port Phillip District, bringing with him a select group of Aboriginal guides from Tasmania, including a woman called Truganini. He could never have foreseen the dramatic and tragic consequence.

Sometime in August 1841, Truganini left Melbourne with her new husband Maulboyheener travelling toward Westernport, working for food and shelter at stations along the way.

On September 4, they were on James Horsfall’s Ballymarang station, where they were joined by their companions, Peevay, his wife Plorenernoopner, and Maytepueminer, wife of their friend Lacklay who had gone missing. All five were on a mission to find out what had happened to Lacklay, last heard of heading into Lower Westernport in May 1840.

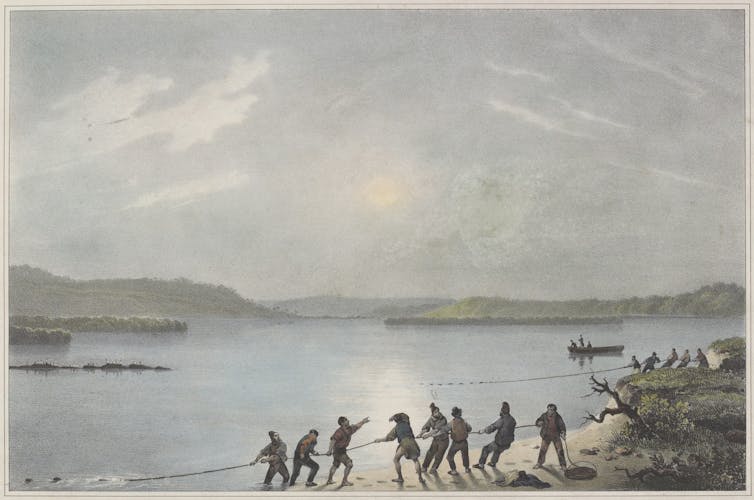

Negotiating the mangroves at the top of Westernport was torturous. The Koo-Wee-Rup Swamp spread for miles to the north and east making it near impossible to find a way through. Truganini and her companions were obliged to make a wide detour around it to find higher ground, where they followed the course of the Lang Lang River to the coast, where massive tide fluctuations had created an extensive inter-tidal zone providing a rich harvest of scallops, mussels, oysters, abalone, limpets, marine worms, crabs and burrowing shrimp.

Despite the evidence of long-standing occupation in the exposed shell middens, the place was empty. When Samuel Anderson and Robert Massie first sailed from Launceston to the eastern shores of Westernport in 1835, they had found the Boonwurrung owners had been extinguished by the cumulative effect of encroachments from Van Diemen’s Land, endemic warfare with the Kurnai from Gippsland and attacks by sealers who “stole” women, all compounded by epidemic disease.

On September 15, Anderson and Massie became aware that Truganini, Maulboyheener, Peevay, Plorenernoopner and Maytepueminer had established camp on their pastoral lease on the Bass River. The two squatters knew members of the group very well from their time working for the Van Diemen’s Land Company, where Anderson had been a bookkeeper and Massie the engineer. If anyone in Lower Westernport knew what had happened to Lacklay, it would be these two squatters.

While at Anderson and Massie’s station, the five almost certainly heard the same information they’d given to Assistant Protector William Thomas when he had come looking for Lacklay — known to him as Isaac — in the previous year: that he was last seen in the company of settler who lived at the end of Westernport Bay. Further inquiries by Thomas established the man in question was the skipper of a cutter that had sailed away from the far eastern tip of Westernport Bay. On board where a woman and her three children, plus Lacklay and an unnamed German man as the crew.

The night they sailed, a heavy squall had swept in from the Tasman Sea and the boat was presumed to have capsized, with everyone drowned, though no bodies or pieces of wreckage had been recovered. Thomas was not convinced, noting in the margin of his journal “the death of Isaac supposed”.

Thomas was right to have reservations about this narrative of death by drowning. The truth, only established 176 years later, was that the cutter did not capsize, but sailed all the way to the remote whaling port of Kororareka in New Zealand. At the time, there was no conceivable way that anyone in Port Phillip could have known the boat had managed to sail across the Tasman Sea.

Lacklay’s disappearance was left to speculation. A story that made much more sense than drowning was that he had been shot by a settler, a narrative everyone in Port Phillip was familiar with. Truganini and Maulboyheener had heard that version of the story too, and now were in Lower Westernport to investigate.

After a leisurely stay at Anderson and Massie’s run, the five moved off on September 29. They crossed the Powlett River and made camp close to the home of William Watson. He was the sole settler below the Bass River, having very recently arrived with his wife, daughter and son-in-law, Walter Ginman, in May 1841. Watson was employed by a consortium of investors to work the seam of coal that Anderson had discovered. He had sunk a shaft into the coal seam near the mouth of the Powlett River, where he built a rudimentary hut just above the high-water mark.

Watson welcomed Truganini and her friends, giving them tea and sugar and even lending them a kettle. On October 2, the fourth day of their visit, Watson and Ginman departed for the mine, and the five approached the hut and lingered in the yard until Mrs Watson came out to give them some more tea and sugar.

Some time later, the women began to scatter the bark from their shelters and pack up their belongings, while the men went to the hut to return the kettle.

Once the men gained entrance to the hut, the tone of their interactions suddenly shifted. The reasons why would only become clear much later.

Peevay went to look for Watson’s guns, while Maulboyheener took Mrs Watson and her daughter by the shoulders to propel them outside. There Truganini and Maytepueminer pulled them into the bush and pointed them in the direction of safety at Anderson and Massie’s station. Meanwhile, Peevay and Maulboyheener systematically stripped the hut of food staples, blankets, clothing, an axe, two guns and a supply of buckshot. After setting fire to the hut, the five loaded up their plunder and followed the river towards the coast.

Early that evening, Peevay and Maulboyheener lay concealed in the low coastal heath watching Watson and his son-in-law returning from the mine. When the two men came into range, they fired a volley of shots from several guns, hitting Ginman in the calf and slightly wounding Watson in the foot and elbow. Hobbling towards their hut, the two men saw their home was a smouldering ruin and their wives had vanished. It was well after dark when they reached Anderson and Massie’s station and found their wives unharmed. The next day, Massie supplied Watson with a brace of firearms and two of his workers for a search party.

Peevay and Maulboyheener must have known that Watson would come looking for them, and that he would likely shoot them on sight, yet they lingered at the Powlett River mouth for another four days.

Staying low, with the heath to provide cover, the five kept careful watch for Watson’s search party. From a high point on the sand dunes, they had an excellent view of the flat country to the north and east, the direction they knew danger would come from. They managed to avoid detection until the evening of October 5, when Watson caught a glimpse of Maulboyheener standing on a high dune. Several shots were fired, failing to wound Maulboyheener, although a bullet came close enough to make a neat hole in the coat he was wearing.

Alert to the danger from Watson’s party, Truganini’s group failed to notice six unarmed men approaching from the south, walking along the beach to Watson’s mine in the late afternoon on October 6. The six men had walked overland from the whaling station at Lady’s Bay, on Wilson’s Promontory, more than 50 miles away. Two of the whalers, known as Yankee and Cook, had set out to locate the miners while their companions entered the hut to rest. Minutes later, two shots rang out in quick succession.

Maulboyheener and Peevay had each fired, first one then the other, in such quick succession there was no time between to reload with powder and shot. Having seen the two men fall, Maulboyheener kept watch from the top of the dune while Peevay, Truganini, Plorenernoopner and Maytepueminer went down to the beach to check the fallen. Lying on the beach were two men they had never seen before: a shot had hit one in the head, killing him instantly, while the other had entered the second man’s side, leaving him grievously wounded and in agony.

The four returned with this terrible information to Maulboyheener, who pulled up a couple of strong tree roots and went alone to the beach to dispatch the wounded stranger with heavy blows to the back of his head. Watching from above, the three women cried in distress.

They were not the only ones watching. Having been woken by the gunshots, two more whalers, Robbins and Evans, stepped outside the hut to look about. They saw a party of four or five people, with what looked like two guns visible on a high dune some 200 yards away. The whalers could not distinguish whether these figures were male or female, but they observed some of the group going down to the beach, leaving a person with a gun watching from above. When they returned, the one who had been watching went down to the beach alone.

Believing they had seen a group of miners hunting birds or kangaroos, Robbins and Evans concluded there was no reason to be alarmed and went back inside to sleep. Waking about an hour later, Evans was disturbed to see his companions Yankee and Cook had not returned. This time he went to search for them. He was a few yards from the hut when Watson’s search party materialised, with their guns aimed right at him. Evans talked quickly and established that none of these men had fired the shots he’d heard earlier.

Alarmed, he enlisted Watson’s party to help search for Yankee and Cook and found their bodies on the beach, their blood staining the sand. Yankee was already cold, with a bullet wound behind his ear. Cook had a deep wound in his side and had been bludgeoned on the back of his head.

It was another six weeks before the five were captured before dawn on November 20, in the coastal heath just south of the murder site. The search party was led by Land Commissioner Frederick Armand Powlett, after whom the river was named. It was comprised of 18 soldiers and policemen, reinforced by four settler volunteers with seven Kulin men as trackers.

Once caught, Truganini, Peevay and Maulboyheener were taken by Powlett to point out the exact place of the murders. On locating the spot, Truganini explained only one shot had been fatal and Maulboyheener had used sticks to beat the wounded man’s head.

“What could make you do it?” Powlett demanded. “We thought it was Watson,” Maulboyheener volunteered, and then fell silent.

Truganini and her companions arrived in Melbourne in chains on November 26. They were taken to the watchhouse, where committal proceedings commenced almost straightaway. Statements were taken from the whaler Evans, from Watson and his wife, from Powlett and members of the search party.

When the display of damning evidence concluded, Maulboyheener made a garbled attempt at a defence. Watson had tried to kill him, he explained, and when he saw the whalers he thought it was Watson and had fired his gun.

On December 2, Robinson and the Methodist minister Reverend Joseph Orton went to speak with the accused men. Peevay remained silent, but Maulboyheener gave an explanation for their otherwise inexplicable actions. Both Robinson and Orton separately recorded in their journals how Maulboyheener explained that James Horsfall of Ballymarang station had told them Watson had in fact killed their friend Lacklay. The men were sentenced and publicly hanged on January 20, 1842.

Edited extract from Truganini: journey through the apocalypse by Cassandra Pybus, published by Allen & Unwin.![]()

Cassandra Pybus, Adjunct Professor in History, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.