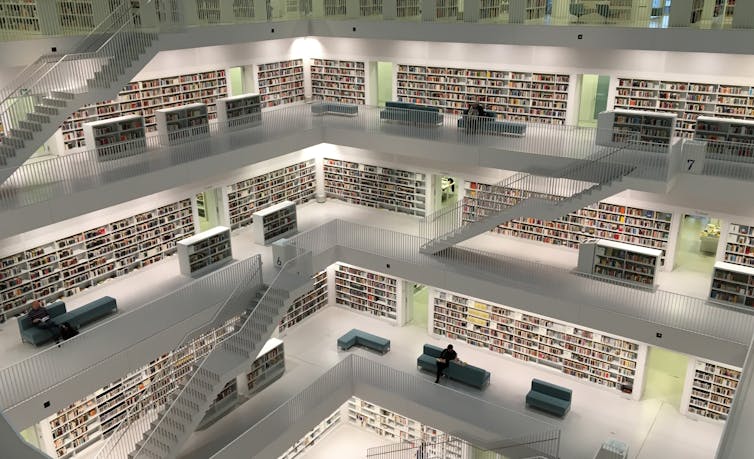

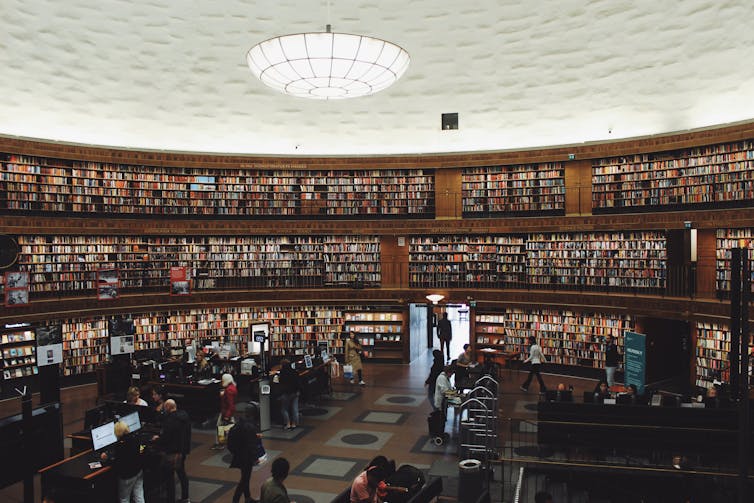

Patrick Robert Doyle /Unsplash

Paulette Rothbauer, Western University

How often do we hear that libraries aren’t just about books anymore? They are makerspaces with 3-D printers, scanners, laser vinyl cutters and routers. They provide green rooms, sewing machines, button makers, and tools like drills, saws and soldering irons. They are places to borrow seeds, fishing rods, cake making supplies, binoculars, laptops and tablets, radon detectors, musical instruments, bicycles and take-home wifi hotspots. They are important sites for learning with services dedicated to today’s newest literacies — coding, gaming, robotics and how to spot fake news.

There are consequences of these ideas and news that push books and reading to the margins in the commentary on the latest trends in public libraries.

One such consequence might be the disavowal of public librarians’ unique, professional knowledge base related to books and reading. Another might be the abdication of a mandate related to the promotion of reading as a social good.

Today’s libraries do build community, support healthy living, promote knowledge and provide space for city sanctuaries. But it is critical that libraries continue to be about books and reading, and that Canadians understand the high value of well-staffed, well-stocked and well-funded libraries.

The news isn’t that library services and programs have moved beyond books, it’s that public libraries are still very much about books.

I’m a researcher and educator in Library and Information Science, and I’ve been studying reading practices for nearly twenty years — those of teenagers, young adults and older adults. My research relies on the perspectives of people who like to read and choose to read for pleasure.

With my colleagues Catherine Ross and Lynne McKechnie at Western University, I’ve published two editions of a book about how reading matters to people, libraries and communities, and I talk about this work in two podcasts: Reading Still Matters and What Do You First Remember about Reading.

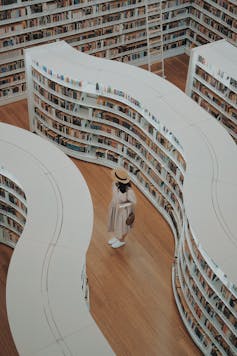

Tobias Fischer / Unsplash

I am not lamenting that this is how libraries always have been and, therefore, always should be. Of course, libraries have never been only about books! But reading and books are more important than ever for contemporary society, and public libraries occupy a unique position as a public reading institution.

Reading matters

There are so many reasons why reading matters. As UCLA literacy scholar Maryanne Wolf so compellingly argues, learning how to read and the habits of deep reading connect in important ways to brain circuitry related to our capacities for critical thinking, empathy and reflection. Reading matters for the ways our brains develop, and being able to read deeply affects the way we think and feel. This has consequences for how we live our lives, but also for how we make judgements about the world and our places in it.

The habit of reading carries many other rewards, among them improved language acquisition and other literacy advantages, as well as therapeutic benefits related to mental wellbeing. We know that reading brings comfort to readers. One large-scale study even found that people who read books also live longer lives in which to read them.

Unsplash

In my research I’ve interviewed young adults about the role of reading in their lives. They told me that reading helps them to explore and understand their identities. It allows them to exercise autonomy and independence. Reading gives them knowledge and experience of the world which, in turn, shows them new possibilities for their own lives.

Reading among older adults can support resilience and contemplation, and conversations about reading can promote a reflective stance on one’s life.

Payton Chung/Flikr, CC BY

Reading develops the brain. Reading helps us sort out who we are, and who we might become, throughout the entirety of our lives. Through reading we understand where other people are coming from too, including those with whom we disagree.

Reading connects us to people in communities that organize around and through reading. Reading gives us space and time to slow down, pause and contemplate even in these hypermediated times.

People learn to love reading by seeing others do it, by being mentored, by making voluntary choices about what to read and by reading themselves, over and over again. This is good news for us because we already have accessible sites in our communities that can support the reading habit — I’m talking about public libraries, of course.

The value of a librarian

Libraries are the only places where we can find educated workers who know about reading and genres, and who are trained in how to best connect readers with what they want to read. Public library systems also have wide and deep collections of reading materials in all formats that go beyond current bestsellers and dominant tastes of the purchasing public. Public libraries are places where people can go to make reading choices for whatever reasons they choose and for whatever ends, and without having to spend a dollar.

Arif Riyanto/Unsplash

Reading generates community in public libraries through programming like book discussion groups, author readings, reader reviews and one-book-one-community events. Because public libraries do all this, they are one of the best supports for books and reading in our society. Depending on who you are, or where you live, public library systems might be your only, your best or your preferred option for getting reading materials. Even people who may never use libraries still think they are good for their communities.

As many people who think that books and reading turn people away from libraries, there are those who think books and reading are the library’s signature brand.

The most recent BookNet Canada annual survey found that 78 per cent of the adults surveyed had read a book in the past 12 months, and most read on a weekly or daily basis. And a study by the American-based non-profit Online Computer Library Center found that Canadians borrowed nearly twice as many books from public libraries than were purchased in bookstores.

Public libraries support a positive culture of reading by making reading materials available, accessible and connecting readers of all ages and with a variety of needs to books of all kinds.

So, let’s dispense with the tired idea of “libraries aren’t just about books anymore” and instead, celebrate how libraries are both about books and reading, and all the other myriad ways that they support literacy, learning, culture and community.

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter. ]![]()

Paulette Rothbauer, Associate Professor, Library and Information Science, Western University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.