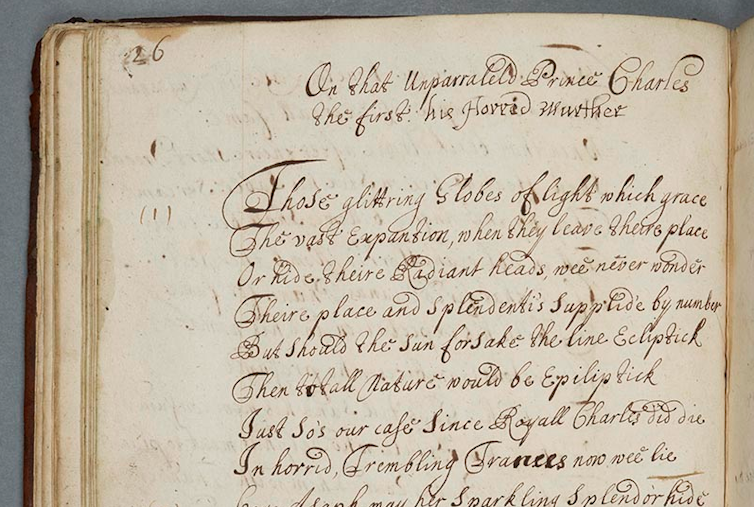

University of Leeds Library, Brotherton Collection, MS Lt q 32, CC BY-NC-SA

Samantha Snively, University of California, Davis

In 1996, a graduate student named Mark Robson was creating a digital catalog of the University of Leeds’ Brotherton Library when he discovered a small manuscript on the shelf. The elegantly titled “Poems Breathed Forth by the Noble Hadassas” contained 120 poems and a half-finished prose romance.

As far as Robson could tell, the manuscript hadn’t been read in over 250 years. He hadn’t heard of the “Noble Hadassas” – nor had anyone he asked.

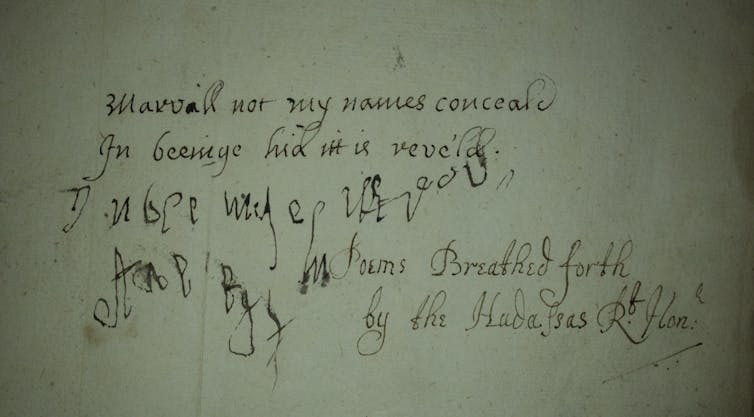

But a riddle scribbled in the manuscript offered a hint about her true name: “Marvel not my name’s concealed / In being hid it is revealed.”

University of Leeds Library, Brotherton Collection, MS Lt q 32., CC BY-NC-SA

In the Biblical story of Esther, “Hadassah” is Esther’s Jewish name. In early modern England, “Hester” and “Esther” were versions of the same name. They’re also anagrams. That allusion to “Esther” – in addition to a couple of references to an estate named Broadfield – gave scholars just enough evidence to search public records for possible authors.

The mystery manuscript turned out to be a collection of poems by a 17th-century English woman named Hester Pulter.

At first glance, the verses of a self-taught, unpublished poet might not seem remarkable. But Pulter was writing in an era of chaos and change in England. She was eager to explore some of the most exciting scientific ideas of the time. And in a time when women were expected to be silent and chaste, she took risks in her poetry and confidently expressed her ideas.

Now, a collaboration between literary scholars across the globe is bringing Hester Pulter’s poems to the public, in the form of an open-access digital edition called The Pulter Project, which launched on Nov. 15, 2018.

Who was Hester Pulter?

Pulter was born into the aristocratic Ley family in 1605 and married Arthur Pulter when she was relatively young. After marrying, she spent much of her life at the isolated Pulter estate, which was over a day’s journey from London. She wrote most of her poems at home and would occasionally travel to London to visit other family members.

Since Pulter mainly kept to herself and rarely left her home, most of what we know about Hester comes from public records. She gave birth to 15 children, only two of which survived to adulthood, and lived through the English Civil War, which lasted from 1642 to 1651.

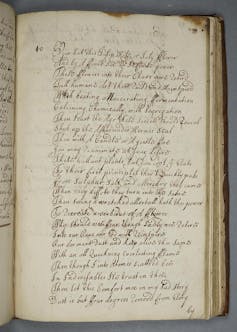

University of Leeds Library, Brotherton Collection, MS Lt q 32

Literary scholar Alice Eardley, who produced the first scholarly edition of Pulter’s works in 2014, has suggested that Pulter’s relative isolation inoculated her from pressure by readers or literary society to conform to a certain style or subject matter. It gave her the freedom to write innovative, opinionated, emotionally complex poetry.

Pulter’s poems, which range from the political to the autobiographical, appear to have been written throughout the 1640s and 1650s. In the 1660s, Hester worked with a scribe to create a presentation copy of her draft poems, making notes and annotations on the manuscript.

It’s likely she never intended to publish her poems, however. In 17th-century England, women who published risked being seen as vulgar and sexually suspect. In order to avoid slander, the few women who did publish usually wrote about topics more aligned with proper womanly values: household guides, devotional books and diaries or memoirs of their husbands.

An aristocratic woman like Hester would have been expected to behave modestly, keep quiet and focus on her household rather than write about political conflicts and scientific experimentation. Pulter’s small family may have read her work, but it seems that her poems sat untouched after her death until they were rediscovered in 1996.

Poetry that’s observant, personal and political

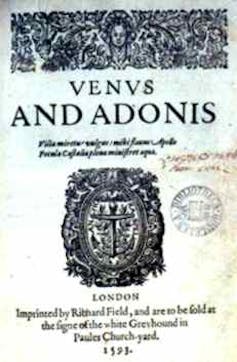

Although Pulter lived a relatively isolated existence, her poems reveal a deep intellectual engagement with the most pressing issues and ideas of the mid-1600s. From the references she makes in her work, it’s clear that she had read works of natural history, alchemy and descriptions of America like William Wood’s “New England’s Prospect.”

She also appears to have kept up with major scientific discoveries, including Galilean astronomy and the microscope. In “Universal Dissolution,” she acknowledges Galileo’s discoveries, describing the sun as the “front and center of all light,” the star around which all other “orbs perpetually do run.”

Pulter was also a keen observer of nature. In “The Pismire,” she describes watching an ant colony at work for an afternoon. “View But This Tulip” shows off her familiarity with alchemy and early experimental practices, and in it she begins to think about the human body as composed of recyclable atoms. These poems place her within a culture of experimental observation that was part of the rise of modern science.

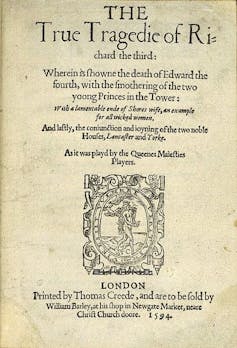

And she certainly didn’t shy away from expressing her political views.

Hester’s parents were Royalists – supporters of Charles I – and she remained a Royalist even when many of her extended family and neighbors supported Parliament instead. Many of her poems express grief at the havoc the civil war caused in England, and mourn a breakdown of religious and social hierarchy.

Scottish National Gallery

In “On that Unparalleled Prince Charles, His Horrid Murder,” she compares a country without a king to the universe without a sun, both of which fall into chaos.

But her political poems avoid outright tribalism. Instead, they’re nuanced and well-informed, and they critique the ruling class for their role in social collapse.

Pulter is equally comfortable writing about personal experiences like her illnesses or a child’s death. She surveys the effects of time on her body in “Made When I Was Sick, 1647,” and in “Upon the Death of My Dear and Lovely Daughter, Jane Pulter,” deals with the grief of losing yet another child. It’s tinged with envy of parents with healthy children:

All you that have indulgent parents been,

And have your children in perfection seen

Of youth and beauty: lend one tear to me,

And trust me, I will do as much for thee,

Unless my own grief do exhaust my store;

Then will I sigh till I suspire no more.

She also expresses early feminist ideas, and addresses, in complex ways, how society constricts women’s behavior, devalues their work and diminishes their intellectual value.

From “Why Must I Thus Forever Be Confined?”:

Why must I thus forever be confined

Against the noble freedom of my mind?

Whenas each hoary moth, and gaudy fly

Within their spheres enjoy their liberty.

Reaching new readers

Hester Pulter is clearly worth knowing. Her works speak to the major issues of 17th-century England and provide a rare lens on English culture.

In an effort to bring Pulter’s poems to the public, early modern literature professors Wendy Wall and Leah Knight created The Pulter Project. They collaborated with a host of other scholars from the U.S., Canada, Australia and England to create a free, digital edition of Pulter’s works.

The Pulter Project allows readers to toggle between scans of the manuscript, basic and annotated editions of poems, and explanatory notes. Readers can also explore “curations” for each poem, which are images and selections from texts relevant to the content of a given Pulter poem.

Editors draw on their expertise of 17th-century English culture to contextualize the poems and also make connections to modern culture. The curated materials for “Made When I Was Not Well,” for example, discuss “invisible woman syndrome,” the social phenomenon of women disappearing from public view when they reach middle age, or are ridiculed and criticized for attracting public attention.

Curations for “My Love is Fair” explore racialized beauty standards, topics just as relevant for 17th-century readers as they are for today’s intersectional feminists.

The Pulter Project shows what’s possible when the literary canon is expanded to include new writers and more women. Poets like Hester Pulter change our understanding about who could – and did – participate in the scientific, political and intellectual debates of centuries ago.![]()

Samantha Snively, PhD Candidate in Early Modern Literature, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.