The link below is to an article that looks at Instagram tips for Librarians.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/08/28/instagram-tips-for-librarians/

The link below is to an article that looks at Instagram tips for Librarians.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/08/28/instagram-tips-for-librarians/

Tom Collins, University of Stirling

My first job as a trainee reporter was on a Sunday title. Sundays are a breed apart. We had contempt for our daily sister, were drunk until Thursday and staffed by some of some of the oddest journalists in town. Unsurprisingly, the paper doesn’t exist any more.

There is a different rhythm to newsgathering. Much of the Sunday paper has to be away early, with stories that won’t date. Front page leads have to be exclusives, it’s just too risky relying on events to bail you out – even in Northern Ireland in the 1980s where I was working. This is one reason why the sting and the “kiss-and-tell” are among Sunday staples.

If you are a Sunday paper news editor, you live in fear that the splash (the front page story) you have been nursing all week will leak to another title. The news business is a kleptocracy, and colleagues on your sister title are the enemy. All’s fair in love, war and newsgathering.

Sunday newspaper readers are different, too. They still have a little time on their hands, and a desire to be entertained. They will frequently buy titles at odds with their daily habits: Guardian readers flirting with the Sunday Times; Sun readers, bereft of the News of the World, picking up the Sunday Mirror or heading “upmarket” to the Mail on Sunday.

Sunday is also the day readers are tempted to take a second title; and in those parts of the UK the BBC euphemistically calls “the nations and the regions”, indigenous papers rub shoulders with the big London players from what is still called Fleet Street.

But as the economics of publishing a newspaper become increasingly challenging, stand-alone titles published once a week look like a luxury to the accountants who now run media organisations. So seven-day operations make sense. In 2012, Rupert Murdoch replaced the discredited News of the World with a Sunday edition of the Sun.

Newsquest executives in Scotland came to the same conclusion when they announced in August that the Herald – its daily broadsheet – was to run seven days a week. The victim was the Sunday Herald, then without an editor.

In normal circumstances, that would have been that. But this is Scotland, and Scotland is not normal. Newsquest’s problem was the Sunday Herald’s editorial support for Scottish independence. Taken down that road by its urbane editor, Richard Walker, the Sunday Herald was the lone media voice supporting independence in the 2014 referendum. Walker went on to become founding editor of the National – designed to tap into nationalist sentiment after the independence referendum.

Although the Herald claims to be neutral on independence – even the dogs in the street know where it sits on the issue. It may not wear a sash and a bowler hat, but it is temperamentally unionist.

With the SNP now established as the natural party of government in Scotland, and with a second independence referendum on the political agenda, killing off the only Sunday in favour of Scotland as a sovereign nation would have displayed a distinct lack of pragmatism.

So, against the tide of consolidation, Newsquest’s single title was replaced by two. Say hello to the “neutral” Herald on Sunday in a racy tabloid livery, and the Sunday National – with Richard Walker again as launch editor.

It’s a brave move for both titles. It is notoriously difficult to persuade readers to change their habits. Can a Herald reader who is wedded to the Observer or Mail on Sunday be seduced back? And what about the fledgling National? It’s tough out there.

The journalism is solid, but – in the first two weeks at least – neither generated the front pages they needed to compete effectively. Rule 101 of a launch edition is to have an exclusive. The Herald’s “Lifeline to Scotland’s islands in jeopardy” did not cut it. The Sunday National led on “Boris ‘set to go for PM’ … and trigger Indyref2”. Billed as an “exclusive”, it was one of those exclusives nobody else would want.

Inside, the National was pacier than the Herald. Even Sundays need news, and it delivered. The internet sensation “giggling granny” was a classic Sunday read, and Jennifer Johnston’s big spread on Scotland’s postcode lottery for primary one parents deserved its prominence.

Foreign correspondent David Pratt brings insight, gravitas and an international perspective to the Sunday National’s broadsheet Seven Days section; its news and features agenda is not quite as unremittingly politically driven as the daily, though Nicola Sturgeon got star billing.

The Herald suffers most from the transition. In tabloid form, it’s like an ageing uncle wearing a baseball cap. The daily broadsheet can sell a story; on the tabloid, the squeezed-in lead barely makes a splash. Inside, the flow of news and features is clunky. “The Week” section, opening the paper, is a mess. A spread on Strictly Come Dancing up front jarred, and the big read on pages six and seven kills the pace up front.

That may change as the paper settles down. But it should be taken as a warning not to mess with the format of the daily, especially if trying to align the titles.

Oddly, both share the same sports coverage and an unbranded Sunday Life supplement. The National needs it to bulk up. It’s a catch-all lifestyle supplement that doesn’t have a clear sense of purpose. The papers also share David Pratt – a great journalist, but sharing writers and sections muddies the waters. Sundays need to be individualistic.

At their best, Sundays are distinctive, tribal and totally attuned to their readers. If they are to carve out a place for themselves, these two new Sundays are going to have to do more to break exclusives that set the agenda for the week ahead – and give Scottish readers the excuse they need to change their buying habits.![]()

Tom Collins, Senior lecturer, Communications, Media and Culture, University of Stirling

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tomas Bokedal, University of Aberdeen

In the years after Jesus was crucified at Calvary, the story of his life, death and resurrection was not immediately written down. The experiences of disciples like Matthew and John would have been told and retold at many dinner tables and firesides, perhaps for decades, before anyone recorded them for posterity. St Paul, whose writings are equally central to the New Testament, was not even present among the early believers until a few years after Jesus’ execution.

But if many people will have an idea of this gap between the events of the New Testament and the book that emerged, few probably appreciate how little we know about the first Christian Bible. The oldest complete New Testament that survives today is from the fourth century, but it had predecessors which have long since turned to dust.

So what did the original Christian Bible look like? How and where did it emerge? And why are we scholars still arguing about this some 1,800 years after the event?

Historical accuracy is central to the New Testament. The issues at stake were pondered in the book itself by Luke the Evangelist as he discusses the reasons for writing what became his eponymous Gospel. He writes: “I too decided to write an orderly account … so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught.”

In the second century, church father Irenaeus of Lyons argued for the validity of the Gospels by claiming that what the authors first preached, after receiving “perfect knowledge” from God, they later put down in writing. Today, scholars differ on these issues – from the American writer Bart Ehrman stressing how much accounts would be changed by the oral tradition; to his Australian counterpart Michael Bird’s argument that historical ambiguities must be tempered by the fact that the books are the word of God; or the British scholar Richard Bauckham’s emphasis on eye-witnesses as guarantors behind the oral and written gospel.

The first New Testament books to be written down are reckoned to be the 13 that comprise Paul’s letters (circa 48-64 CE), probably beginning with 1 Thessalonians or Galatians. Then comes the Gospel of Mark (circa 60-75 CE). The remaining books – the other three Gospels, letters of Peter, John and others as well as Revelation – were all added before or around the end of the first century. By the mid-to-late hundreds CE, major church libraries would have had copies of these, sometimes alongside other manuscripts later deemed apocrypha.

The point at which the books come to be seen as actual scripture and canon is a matter of debate. Some point to when they came to be used in weekly worship services, circa 100 CE and in some cases earlier. Here they were treated on a par with the old Jewish Scriptures that would become the Old Testament, which for centuries had been taking pride of place in synagogues all over latter-day Israel and the wider Middle East.

Others emphasise the moment before or around 200 CE when the titles “Old” and “New Testament” were introduced by the church. This dramatic shift clearly acknowledges two major collections with scriptural status making up the Christian Bible – relating to one another as old and new covenant, prophecy and fulfilment. This reveals that the first Christian two-testament bible was by now in place.

This is not official or precise enough for another group of scholars, however. They prefer to focus on the late fourth century, when the so-called canon lists entered the scene – such as the one laid down by Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, in 367 CE, which acknowledges 22 Old Testament books and 27 New Testament books.

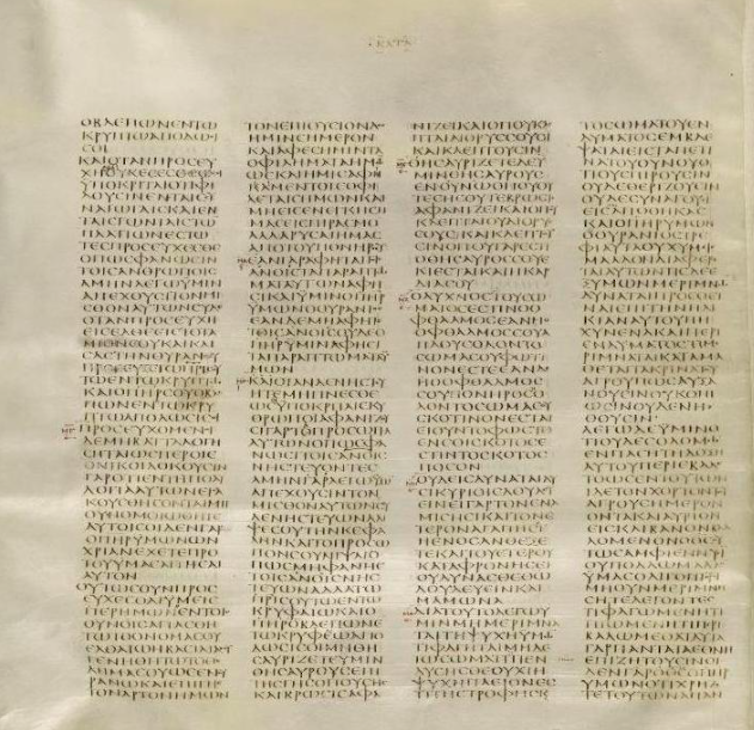

The oldest surviving full text of the New Testament is the beautifully written Codex Sinaiticus, which was “discovered” at the St Catherine monastery at the base of Mt Sinai in Egypt in the 1840s and 1850s. Dating from circa 325-360 CE, it is not known where it was scribed – perhaps Rome or Egypt. It is made from parchment of animal hides, with text on both sides of the page, written in continuous Greek script. It combines the entire New and Old Testaments, though only about half of the old survives (the New Testament has some fairly minor defects).

Sinaiticus may not be the oldest extant bible, however. Another compendium of Old and New Testaments is the Codex Vaticanus, which is from around 300-350 CE, though substantial amounts of both testaments are missing. These bibles differ from one another in some respects, and also from modern bibles – after the 27 New Testament books, for example, Sinaiticus includes as an appendix the two popular Christian edifying writings Epistle of Barnabas and Shepherd of Hermas. Both bibles also have a different running order – placing Paul’s letters after the Gospels (Sinaiticus), or after Acts and the Catholic Epistles (Vaticanus).

They both contain interesting features such as special devotional or creedal demarcations of sacred names, known as nomina sacra. These shorten words like “Jesus”, “Christ”, “God”, “Lord”, “Spirit”, “cross” and “crucify”, to their first and last letters, highlighted with a horizontal overbar. For example, the Greek name for Jesus, Ἰησοῦς, is written as ⲓ̅ⲥ̅; while God, θεός, is ⲑ̅ⲥ̅. Later bibles sometimes presented these in gold letters or render them bigger or more ornamental, and the practice endured until bible printing began around the time of the Reformation.

Though Sinaiticus and Vaticanus are both thought to have been copied from long-lost predecessors, in one format or the other, previous and later standardised New Testaments consisted of a four-volume collection of individual codices – the fourfold Gospel; Acts and seven Catholic Epistles; Paul’s 14 letters (including Hebrews); and the Book of Revelation. They were effectively collections of collections.

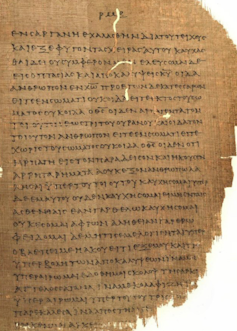

But in the absence of a single book prior to the fourth century, we have to content ourselves with the many surviving older fragments sensationally found during the 20th century. We now have some 50 fragmentary New Testament manuscripts written on papyrus that date from the second and third centuries – including the valuable Papyrus 45 (fourfold Gospel and Acts), and Papyrus 46 (a collection of Pauline letters). In all, these comprise almost complete or partial versions of 20 of the 27 books in the New Testament.

The quest will likely continue for additional sources of the original books of the New Testament. Since it is somewhat unlikely anyone will ever find an older Bible comparable with Sinaiticus or Vaticanus, we will have to keep piecing together what we have, which is already quite a lot. It’s a fascinating story which will no doubt continue to provoke arguments between scholars and enthusiasts for many years into the future.![]()

Tomas Bokedal, Associate Professor in New Testament, NLA University College, Bergen; and Lecturer in New Testament, University of Aberdeen

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tony Hughes-D’Aeth, University of Western Australia

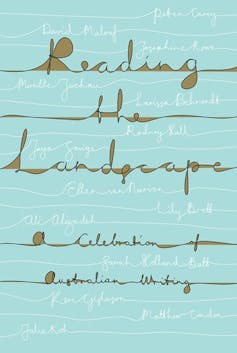

Review: Reading the Landscape, a Celebration of Australian Writing (UQP).

It is actually quite difficult to imagine what Australian literature would look like without the University of Queensland Press (UQP). Since it was established in 1948, it has done as much as any Australian publisher to shape Australian creative writing. The title of this excellent anthology Reading the Landscape refers to this literary landscape rather than any thematic interest in Australia’s land.

Whether writers like David Malouf, Rodney Hall, Peter Carey, Doris Pilkington-Garimara and Alexis Wright would have become the writers they became without UQP is a moot point. One assumes, with the benefit of hindsight and the stratosphere they now inhabit, that they certainly would have. How could we not have Oscar and Lucinda, Remembering Babylon, Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence and Carpentaria? How could they not exist? But the fact is that each of these writers, and dozens of others, were first published by UQP.

Against considerable economic pressures, UQP is one of a handful of Australian university presses that continue to produce quality scholarly publications for academic and general markets. While academic scholarship is considered the natural province of a university press, UQP is distinctive in having developed significant fiction and poetry lists from the late 1960s.

Recently, the University of Western Australia’s UWAP has followed UQP in developing fiction (and creative nonfiction) and poetry lists, and last year UWAP author Josephine Wilson won the Miles Franklin for her novel Extinctions. But UQP’s record of discovering, nurturing and supporting Australian writers, is really without peer in the other Australian university presses, and unique in world terms.

Reading the Landscape is a cross-section of living writers who currently publish with UQP or have in the past. At least three generations feature — those who debuted in the 1970s and 80s, those who appeared for the first time in the 90s and 2000s, and the current range of new writers.

In the first generation, we see not only Malouf, Carey and Hall, but important writers like Nicholas Jose, Peter Skrzynecki and Gabrielle Carey. In the next generation, there are writers like Lily Brett, Melissa Lucashenko, Larissa Behrendt, David Brooks, Venero Armanno and Samuel Wagan Watson. And finally, we have writers only recently to emerge such as Jaya Savige, Julie Koh and Ellen van Neerven.

Those familiar with some of those writers will be reminded, in this anthology, of just why they have been celebrated. Rodney Hall’s Glimpses of Lost Europe, for instance, is a charming reminder of his effortless brilliance. It begins in 1954 like this:

Dr Bródy – philosopher, philologist and metaphysician – was grateful to find work in Brisbane as an umbrella salesman.

And spins outwards from there. Various trends and movements suggest themselves from these contributions. One is the turn towards factual stories in the genre now known as creative non-fiction. Another is the rise of the young-adult genre as a powerful and lucrative publishing phenomenon.

One of the creative non-fiction highlights of this anthology is Patti Miller’s riveting account of her uncle’s hang-gliding accident. Icarus is the spellbinding story of a quiet and meticulous man who becomes, in his 60s, a devoted hang-gliding enthusiast, only to have his spine shattered by an accident while landing.

I was also taken by the quality of the poetry by younger writers like Savige, van Neerven and Ali Alizadeh. Their respective poems were by turns spiky and lyrical, smouldering and rueful. The way that they mix politics and memory, urgency and metaphysics, affirms the continuing possibilities of poetic expression in what often seems like an increasingly prosaic age.

Perhaps most significant, though, is the rise of Indigenous writing visible in the contributions from acclaimed authors like Lucashenko, Behrendt, Wagan Watson and van Neerven (the last three each won the David Unaipon award).

The appearance of modern Indigenous writing is often dated to the publication by Jacaranda Press, another largely independent Brisbane press, of Kath Walker’s (Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s) We are Going in 1965. UQP published Kevin Gilbert’s People are Legends: Aboriginal Poems in 1978, and as Bernadette Brennan reminds us in her fine introduction to Reading the Landscape, the press contributed very significantly to the emerging study of Indigenous writing with seminal monographs on the subject by J.J. Healy and Adam Shoemaker.

Many of the key Indigenous writers to follow in the wake of Oodgeroo, Kevin Gilbert, and Jack Davis have come through UQP, although the WA presses Fremantle Press and Magabala Books have also been crucial. In van Neerven, in particular, one sees a worthy successor to Oodgeroo, as invidious as that comparison might seem. Oodgeroo’s trademark mixture of acerbic humour and gut-punching honesty shines through van Neerven’s verse, and her poem 18C is a fitting conclusion to the anthology.

Written in answer to the recent controversies that have surrounded the anti-vilification provision of Australia’s Racial Discrimination Act, the poem’s 18 stanzas thread in and out of the complexities of black life. The final stanza, and the book’s last words are these:

Courage is telling them what you think of that play, that script they try and write us in will no longer contain us, bring me a new coat of oppression, this one’s wearing thin.

Tony Hughes-D’Aeth, Associate Professor, English and Cultural Studies, University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.