Nefertiti’s Heart by A.W. Exley

Nefertiti’s Heart by A.W. Exley

My rating: 1 of 5 stars

If this book was simply about the mystery and not the ‘romance,’ it could very well be a decent book. It is not the better for the romance, rather the worse. Disappointing.

Nefertiti’s Heart by A.W. Exley

Nefertiti’s Heart by A.W. Exley

My rating: 1 of 5 stars

If this book was simply about the mystery and not the ‘romance,’ it could very well be a decent book. It is not the better for the romance, rather the worse. Disappointing.

Maggie Nolan, Australian Catholic University

Although the 2018 Closing the Gap report on Indigenous disadvantage highlighted the importance of literacy for Indigenous Australians, progress remains slow. But, while reading is widely considered an unmitigated good and a marker of prestige, it is not a simple issue for some Indigenous Australians.

I have been investigating the politics of reading for Indigenous Australians by visiting the Murri Book Club, an Indigenous book club, in Townsville and discussing the role of books and reading in its members’ lives. As one woman told me:

No one ever read to me as a child. The only reading we ever had was church … reading at Bible studies. We had to get hit with a stick to sit still and stop moving and making noises … And so, to me, reading was restrictive, I suppose, and boring because of that part. It was never fun.

One of the concerns for members of the Murri Book Club is that books and reading are linked to the ongoing history of assimilation that, even now, presumes a divide between Indigenous oral story-telling and non-Indigenous literacy. This is why the members of the club show more ambivalence towards reading than might be expected of a typical book club.

Book clubs have been described by scholar Marilyn Poole as “one of the largest bodies of community participation in the arts in Australia”. Current research suggests that these clubs are overwhelmingly white, middle-class, middle-aged and female. Members of most mainstream book clubs are part of what Wendy Griswold has termed “the reading class”, which is small in size but immense in cultural influence.

Read more:

Three reasons why the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians aren’t closing

Janeese Henaway, the Indigenous Library Resources Officer at the library, started the book club in 2011 and introduced me to the group. Janeese was raised just south of Townsville in a town called Ayr. When Janeese was asked to facilitate a book club, it was suggested to her that they follow the model practised by the Brisbane-based Reconciliation Reading Group that has met monthly in the Queensland State Library for over 15 years.

But Janeese was unsure about how to proceed.

I didn’t know at that point how to run the club in a way that was culturally appropriate … I explained that we did not then want to go to a book club and have heavy discussions on Indigenous issues. The group predominantly wanted a light, entertaining and enjoyable experience. Although we’re Murris, we are also readers.

One woman told me she joined the group because she wanted to set an example for her son. While many book clubs operate within an unspoken discourse of self-improvement, it is rare for book club members to be so explicit.

For this member, reading is a cultural resource that carries significant weight. As she tells it, her son is much more interested in (Indigenous) culture and, for him, reading and culture are “two separate things”. She recalls him asking, “Why I gotta read for? I’m gonna be an Island boy, man, when I grow up. You don’t need to read”. For her son, culture is about story, not about reading.

There is a long history, particularly throughout the assimilation era, of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people being actively prevented from speaking their languages. Members of the Murri book club are aware that policies of assimilation mean less access to oral stories. The imposition and authority of the written word can be seen to clash with Indigenous practices of oral story-telling. A commitment to reading can make some Indigenous people feel that they must sacrifice other cultural values that have sustained them as individuals, families and communities for millennia.

Read more:

Read, listen, understand: why non-Indigenous Australians should read First Nations writing

Members of the Murri book club experience this sacrifice as a cultural compromise. One member, an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Indigenous Liaison Officer at a tertiary institution, suggested the solution is more Indigenous-authored texts that record Indigenous knowledge. But he is also aware that the focus on reading has come at a cost:

But these guys … [the others in the Murri book club] I envy them … Like the oral stories are there [for me], but they’re not in that layer that these guys have. And then because of that book, the authority of the book, when you get them old people to talk, they say, ‘Ah, that’s not true. It’s not in a book.’ Only, every now and then, they say, ‘It doesn’t all have to be in a book.’

In response to this recollection of the authority of books as a source of truth, another member responded: “But keep in mind that you were trained in that way … Print had authority over the spoken word.”

Although she loves reading, this member rarely reads the book club books. She comes along primarily for social reasons — for connecting with community. In spite of her love of books and reading, she is very conscious of the fact that books, and the authority of written language, were key tools in undermining oral traditions in her home of the Torres Strait. Indeed, the Murri book club, as a whole, are more aware than most that reading is connected to power.

![]() In their discussions, the Murri Book Club has taken a communal institution so often associated with white, middle-class culture and remade it as a force for decolonising contemporary cultures of reading. It challenges assumptions not only about book clubs, but also about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. While reading can come with significant cultural baggage for some Indigenous people, it can also be a powerful tool.

In their discussions, the Murri Book Club has taken a communal institution so often associated with white, middle-class culture and remade it as a force for decolonising contemporary cultures of reading. It challenges assumptions not only about book clubs, but also about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. While reading can come with significant cultural baggage for some Indigenous people, it can also be a powerful tool.

Maggie Nolan, Senior lecturer in Humanities, Australian Catholic University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Katie Sutherland, Western Sydney University

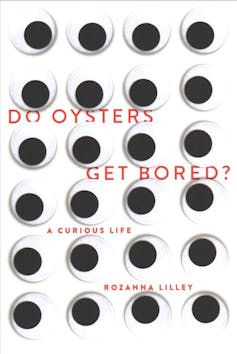

Review: Do Oysters Get Bored? by Rozanna Lilley

At the nucleus of Rozanna Lilley’s memoir, Do Oysters Get Bored? A curious life, is Lilley’s son Oscar, a funny and endearing 12-year-old with a penchant for cartoons, a fear of dogs and a dislike for crying babies. Oscar is autistic, diagnosed at the age of three. But autism is just one small piece in the puzzle of a complex family story, as Lilley unravels memories of her own fraught early years.

Lilley and her sister Kate are the daughters of the late and renowned writers Dorothy Hewett and Merv Lilley. Left wing radicals, the couple and their children lived at the centre of the 1970s arts scene in a bohemian terrace in Jersey Road, Woollahra — an open house frequented by painters, poets, actors and musicians.

Hewett believed in free love and encouraged her girls to have sex from an early age. However, many of Lilley’s sexual encounters as a teenager, and younger, were moments of molestation and predation by the older men who visited their family home that resonate in today’s #MeToo movement. She writes openly about these and also reflects on her mother’s role:

My mother did not intentionally hurt me. But neither did she protect me. She had a pretty good idea of what was going on in her own house and she imaginatively recast these predations as adventures, confirming our familial superiority to restrictive moral norms. Forty years later, I am still trying to come to terms with that carelessly broken girlhood.

At times, the book’s content is intensely confessional and confronting. But the themes of childhood and motherhood are intrinsically linked and it is only fitting that Lilley reflect on her own upbringing as she negotiates how to parent Oscar and his older sister.

While Lilley’s account of her parents’ failings is frank, she also writes of a fondness for her mother and the sense of grief she felt when Hewett died in 2002. Lilley also reflects on caring for her father in his final years with dementia until he died in 2016. As a reader, it is not difficult to empathise with her conflicted emotions around such responsibilities and life events.

Lilley does not sugarcoat the realities of autism either, but compared to some of the other gritty material in the book, her stories of Oscar come as sweet relief. It is in unlikely places, such as a caravan park in Berrara, NSW, that Lilley finds moments of tenderness:

From the ruffled comforts of my bed, I watch the world of the caravan park through the window. And I breathe my son in. Oscar’s round face, caught in the half-light of the summer’s morning, is beautiful beyond reproach.

Oscar is theatrical and Lilley relishes his sense of humour and unique perspective. She describes his attachment to certain objects, his inner fantasy world, his anxieties and fears, and how these traits impact on family life. But she also draws the reader’s attention to her son’s unique creativity and sensitivity, largely through his precocious vocabulary. “A cloud and a moon equal beauty”, he announces one evening on his way to bed, “It’s a once in a lifetime gift!”

The book’s title alludes to a question he asks on a family holiday in Patonga, where, writes Lilley, “fishing boats curtsy on the rolling tide, laden with lacy nets and old salt-encrusted promises”.

“Hey Mum”, asks Oscar, “if you were an oyster, what do you think you would be thinking? Dad, what do you think the life of an oyster would be? Do you think they would be bored?” He goes on to question, “If you were an oyster, would this entire place be the known universe?”

Like many parents of children on the autism spectrum, Lilley has turned to research to better understand her child. She is also a social anthropologist and her portrayal of autism is informed and sensitive. Autism diagnostics are ever evolving and Lilley has handled this well throughout.

She has also “learned to pick her battles” with unhelpful people who are all too quick to pass judgement, writing: “Autism is a shooting gallery, a passing parade occupied by stereotypical figures created through a heady mix of prejudice, ignorance and voyeuristic fascination”.

Lilley’s storytelling is eloquent and touching, with her talent for poetry evident in her writing style. Her prose is complemented by a selection of poems at the end of the book. As a whole, the memoir paints a nuanced picture of the complexity of family life and the dynamic between the individuals who make up this family’s story.

![]() “To paraphrase Henry James”, writes Lilley, “it would be fair to say that all of my family, both more and less eminent, have oddities and disparities that often force one, thinking them over, to wonder what they really quite rhyme to”. Indeed, it is a curious life.

“To paraphrase Henry James”, writes Lilley, “it would be fair to say that all of my family, both more and less eminent, have oddities and disparities that often force one, thinking them over, to wonder what they really quite rhyme to”. Indeed, it is a curious life.

Katie Sutherland, Doctor of Creative Arts Candidate, Western Sydney University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Tony Hughes-D’Aeth, University of Western Australia

What if Australia were to stop farming? At approximately 3% of gross domestic product, the removal of agriculture from the economy would be a significant hit. It would affect our balance of payments — 60% of agricultural produce is exported and it contributes 13% of Australia’s export revenue.

Towns that are slowly dying would collapse, jobs would go. But really the scandal of this thought goes beyond economics and into the very soul of the nation. The crucial insight to emerge from such a thought-experiment is that agriculture in Australia is a religion — it is as much a religion as it is an industry.

The powerful ideological connection between Australia and agriculture is being increasingly and diversely scrutinised and comes to the fore in Charles Massy’s iconoclastic epic, Call of the Reed Warbler: A New Agriculture, A New Earth (2017), which throws into question 200 years of assumptions about what it means to graze animals in Australia.

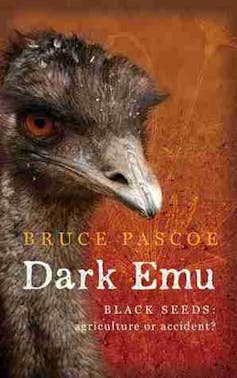

Massy’s joins a spate of recent books that seek to recast the basic assumptions on which Australian agriculture was built. They include Don Watson’s The Bush (2016), Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu, Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? (2014) (which has recently been turned into dance by Bangarra) and Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia (2012). If agriculture is a religion in Australia, these writers are its heresiarchs.

It is a truism that Australia, overwhelmingly urban for most of its modern history, draws its identity disproportionately from “the land”. Those Qantas television advertisements with choirs of angelic children strewn elegantly in front of Uluru or the Twelve Apostles trade on the basic fact that Australians identify and want to be identified with the continent itself.

In this sense, Australia (the continent, the land, the soil, the bush) is imagined as a metaphysical substance which gives unity, meaning and destiny to what might otherwise seem like a collection of recently federated settler colonies, formed to extract resources for the benefit of a once powerful European nation state. The practice of agriculture is central to the belief that Australians as a people are expressive of Australia, the metaphysical ideal. Without this connection between agriculture and Australianness, we couldn’t make sense of such fashion icons as Akubra, Blundstone, Driza-Bone and R.M. Williams.

Serious questions about the way that Australia sustains people through the plants and animals that are husbanded on its ancient soils are not, of course, confined to the past several years. The revision might be traced to Tim Flannery’s The Future Eaters (1994), or even earlier to such seminal works of environmental history as Eric Rolls’ A Million Wild Acres (1981), W.K. Hancock’s Discovering Monaro (1972), and Barbara York Main’s Between Wodjil and Tor (1967) and Twice Trodden Ground (1971).

What each of these writers did was to make the Australian environment, or some part of it, an actor rather than a stage. The environment for these writers was not some broadly passive, albeit resistant, thing out there that needed to be overcome, battled, tamed, brought into submission — it was a dynamic system of interrelated parts, where every action had cascading consequences and complex repercussions.

At the centre of, or just beneath, all of these books is the attempt to try and locate some kind of basic environmental baseline. There seems to be no dispute about the fact that the agricultural colonisation of Australia by Europeans has had far reaching consequences for the organisation of the continent’s biota.

Read more:

Queensland land clearing is undermining Australia’s environmental progress

In almost every possible way the land has undergone serious and widespread interventions. The introduction of new predators, notably cats and foxes, caused (and continues to cause) mass extinctions of species. The introduction of hooved animals, in addition to their utterly different patterns of grazing, also hardened the soil and changed the extent to which rain is absorbed or runs off the surface of the land, often carrying soil into rivers which now run faster but also then silt up and slow down.

The removal of perennial, deep rooted vegetation for annual crops causes groundwater to rise and dissolves salt crystalised in the soil, resulting in soil salinity. Fire regimes have changed radically. Rabbits and other rodents out-compete native herbivores, while European carp have transformed the major river systems of the south east. The list goes on, and it is surprisingly familiar to all of us.

But as these things continue to run rampant, and as major questions begin to be asked about the sustainability of agriculture, we seem to be thrown backwards into the origins of these problems. And as we trace them back we come against the tantalising question of what it was all like before this. Before what? Before the arrival of Europeans. What did Australia look like in 1788, in fact? This is the question that each of these writers seems to be either answering, or at the least reacting against.

In this respect, Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu, which builds in important ways on Gammage’s earlier book, provides the most concerted attempt to answer the question about the quality of the country — in particular, the interface between human and nature — in the pre-colonial epoch. Because of the oral quality of Aboriginal societies, many of these questions have traditionally been considered to fall beyond the province of history proper, and into the study of pre-history (archaeology) and anthropology.

Indeed, there is something of a demarcation dispute around this crucial hinge between Aboriginal and European colonial lifeways. One of the strengths of Pascoe’s book is its ability to bridge archaeology, anthropology, archival history, Indigenous oral tradition and other more esoteric but highly revealing disciplines such as ethnobotany and paleoecology.

The key contention in Pascoe’s book is that the whole distinction between the farming colonist and the hunter-gatherer indigene is based on a radical, and frankly self-serving, misunderstanding of the way that the Indigenous peoples of Australia lived in their countries. Pascoe assembles a persuasive case that Indigenous Australians farmed their land, lived in villages, built houses, harvested cereals, built complex aquaculture systems — possibly the earliest stone structures in human history — and led the kind of sedentary agricultural lives that were meant only to have arrived with Europeans in 1788.

Read more:

The detective work behind the Budj Bim eel traps World Heritage bid

Pascoe is an Indigenous historian and is clearly motivated by a desire to redress the serial denigration of Indigenous people. His cards are on the table, but this does not mean that he is not a rigorous and exacting judge of the historical record.

Massy, for his part, was born and bred on a sheep and cattle farm on the Monaro plain — a farm he has now run for over 40 years. By his own confession, he spent the majority of his farming life assiduously contributing to the problems he is now just as assiduously diagnosing in The Call of the Reed Warbler. The book is in many respect a conversion narrative, documenting the moment when the scales fell from his eyes and he saw truly the world as it was — not a land made efficient and productive by the application of agricultural science, but a land emptied of its relationships and webs of life by a kind of collective psychosis. Farming wasn’t sustaining the land, it was ruining it. It was an extractive industry that had gobbled up thousands of years of sustenance in a few generations of sustained plunder.

Don Watson’s book The Bush is the most literary of these recent contributions, and it moves effortlessly and elegiacally between science, history, reminiscence and anecdote. He has a writing style that is epigrammatic and sonorous, reminiscent of the way that, in an American context, Wallace Stegner treated the tumultuous history of the American Great Plains.

Against the bluff empiricism that underpins Gammage and Pascoe, and the ardour of the convert that galvanises Massy, Watson offers something more elliptical and rhapsodic. He moves from his native Gippsland to Australia at large through a sort of sly mimicry of the discourse of the Australian bush. The bush is both the object of Watson’s study and his linguistic mode, since he draws his wry sensibility directly from Joseph Furphy or Henry Lawson. The distinctive admixture of acerbic humour, dark melancholy and a poignant apprehension of the absurdity of life that was the hallmark of the Bulletin school of writers.

What all of these books are saying, and why they are in fact getting traction now, is that something is broken. These books are not announcing that the environment is broken — they merely mention this in passing, regarding this as beyond any reasonable doubt. Instead, what these books are announcing is that agriculture is broken.

This, in the context of our self-image, is something that is much more terrifying and it will be savagely resisted. But each book is also hopeful in its way. None more than Charles Massy, whose book’s subtitle “A New Agriculture, A New Earth” is openly salvationist and The Call of the Reed Warbler is a detailed plan for the regeneration of degraded pastoral country that allows for both agricultural production and environmental recovery.

A few weeks ago, I was visiting the rock formation we whitefellas have called Wave Rock, in Western Australia’s southern wheatbelt. It is a stunningly beautiful granite outcrop and central to the lifeways of the Noongar people of this region.

What stands out now is the contrast between the cleared fields stretching to the horizon in every direction and this tiny oasis of bushland surrounding the rock. The paleo-river channels that shaped the landscape are now heavily waterlogged by a rising water-table and everywhere you see the signs of salinized soil—dead and dying shrubs and trees.

But as tourists we carefully avert our eyes and pose for photographs at the rock. This is in many ways a microcosm of the determined blindness that these recent books are trying to rectify.

![]() Bangarra’s Dark Emu runs in Sydney at the Opera House until July 14 then will tour to Canberra, Perth, Brisbane and Melbourne.

Bangarra’s Dark Emu runs in Sydney at the Opera House until July 14 then will tour to Canberra, Perth, Brisbane and Melbourne.

Tony Hughes-D’Aeth, Associate Professor, English and Cultural Studies, University of Western Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to a review of the Kobo Clara HD ebook reader.

For more visit:

https://teleread.org/2018/06/30/review-the-kobo-clara-hd-e-ink-reader/

Jakob Povl Holck, University of Southern Denmark and Kaare Lund Rasmussen, University of Southern Denmark

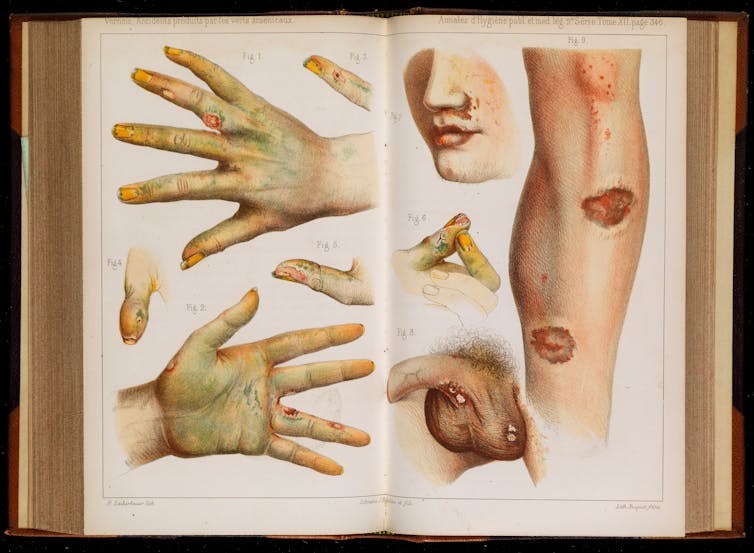

Some may remember the deadly book of Aristotle that plays a vital part in the plot of Umberto Eco’s 1980 novel The Name of the Rose. Poisoned by a mad Benedictine monk, the book wreaks havoc in a 14th-century Italian monastery, killing all readers who happen to lick their fingers when turning the toxic pages. Could something like this happen in reality? Poisoning by books?

Our recent research indicates so. We found that three rare books on various historical topics in the University of Southern Denmark’s library collection contain large concentrations of arsenic on their covers. The books come from the 16th and 17th centuries.

The poisonous qualities of these books were detected by conducting a series of X-ray fluorescence analyses (micro-XRF). This technology displays the chemical spectrum of a material by analysing the characteristic “secondary” radiation that is emitted from the material during a high-energy X-ray bombardment. Micro-XRF technology is widely used within the fields of archaeology and art, when investigating the chemical elements of pottery and paintings, for example.

The reason why we took these three rare books to the X-ray lab was because the library had previously discovered that medieval manuscript fragments, such as copies of Roman law and canonical law, were used to make their covers. It is well documented that European bookbinders in the 16th and 17th centuries used to recycle older parchments.

We tried to identify the Latin texts used, or at least read some of their content. But then we found that the Latin texts in the covers of the three volumes were hard to read because of an extensive layer of green paint which obscures the old handwritten letters. So we took them to the lab. The idea was to filter through the layer of paint using micro-XRF and focus on the chemical elements of the ink below, for example on iron and calcium, in the hope of making the letters more readable for the university’s researchers.

But XRF-analysis revealed that the green pigment layer was arsenic. This chemical element is among the most toxic substances in the world and exposure may lead to various symptoms of poisoning, the development of cancer and even death.

Arsenic (As) is a ubiquitous naturally occurring metalloid. In nature, arsenic is typically combined with other elements such as carbon and hydrogen. This is known as organic arsenic. Inorganic arsenic, which may occur in a pure metallic form as well as in compounds, is the more harmful variant. The toxicity of arsenic does not diminish with time.

Depending on the type and duration of exposure, various symptoms of arsenic poisoning include an irritated stomach, irritated intestines, nausea, diarrhoea, skin changes and irritation of the lungs.

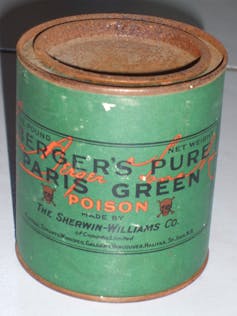

The green arsenic-containing pigment found on the book covers is thought to be Paris green, copper(II) acetate triarsenite or copper(II) acetoarsenite Cu(C₂H₃O₂)₂·3Cu(AsO₂)₂. This is also known as “emerald green”, because of its eye-catching green shades, similar to those of the popular gemstone.

The arsenic pigment – a crystalline powder – is easy to manufacture and has been commonly used for multiple purposes, especially in the 19th century. The size of the powder grains influence on the colour toning, as seen in oil paints and lacquers. Larger grains produce a distinct darker green – smaller grains a lighter green. The pigment is especially known for its colour intensity and resistance to fading.

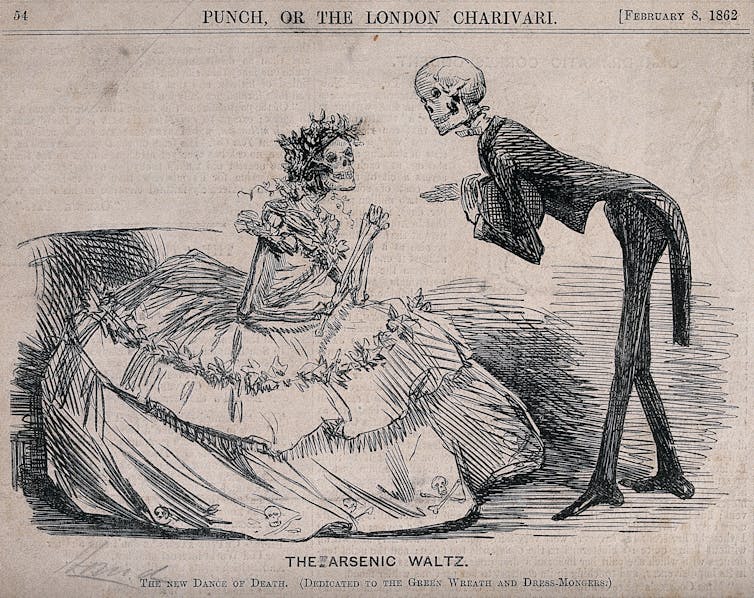

Industrial production of Paris green was initiated in Europe in the early 19th century. Impressionist and post-impressionist painters used different versions of the pigment to create their vivid masterpieces. This means that many museum pieces today contain the poison. In its heyday, all types of materials, even book covers and clothes, could be coated in Paris green for aesthetic reasons. Of course, continuous skin contact with the substance would lead to symptoms of exposure.

But by the second half of the 19th century, the toxic effects of the substance were more commonly known, and the arsenic variant stopped being used as a pigment and was more frequently used as a pesticide on farmlands. Other pigments were found to replace Paris green in paintings and the textile industry etc. In the mid 20th century, the use on farmlands was phased out as well.

In the case of our books, the pigment wasn’t used for aesthetic purposes, making up a lower level of the cover. A plausible explanation for the application – possibly in the 19th century – of Paris green on old books could be to protect them against insects and vermin.

Under certain circumstances, arsenic compounds, such as arsenates and arsenites, may be transformed by microorganisms into arsine (AsH₃) – a highly poisonous gas with a distinct smell of garlic. Grim stories of green Victorian wallpapers taking the lives of children in their bedrooms are known to be factual.

![]() Now, the library stores our three poisonous volumes in separate cardboard boxes with safety labels in a ventilated cabinet. We also plan on digitising them to minimise physical handling. One wouldn’t expect a book to contain a poisonous substance. But it might.

Now, the library stores our three poisonous volumes in separate cardboard boxes with safety labels in a ventilated cabinet. We also plan on digitising them to minimise physical handling. One wouldn’t expect a book to contain a poisonous substance. But it might.

Jakob Povl Holck, Research Librarian, University of Southern Denmark and Kaare Lund Rasmussen, Associate Professor in Physics, Chemistry and Pharmacy, University of Southern Denmark

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article (Blog post) that takes a look at the audiobook vs reading debate.

For more visit:

https://www.offthebeatenshelf.com/blog/ableist-authors

It looks as though Amazon is serious in its battle with book stuffers, shutting down a number of them recently. The link below is to an article that takes a look at some of the action taken.

For more visit:

https://www.bookworks.com/2018/06/book-stuffing-scams-kindle-unlimited/

The new Goodreads Android app has been around for a few weeks now – the links below are to articles that take a look at the new app.

For more visit:

– https://www.goodreads.com/blog/show/1307-introducing-the-all-new-faster-goodreads-android-app-includes-rereads

– https://goodereader.com/blog/spotlight-on-android/goodreads-launches-new-android-app

– https://bookriot.com/2018/07/06/new-goodreads-app/

As we have moved on from the printed vs digital books debate (unlikely), we have now entered the debate over audiobooks vs reading. The link below considers this question.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/07/10/audiobooks-vs-reading/

You must be logged in to post a comment.