The link below is to an article that reports on criticism of the Man Booker for allowing the entrance of USA writers.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jul/08/man-booker-peter-carey-julian-barnes

The link below is to an article that reports on criticism of the Man Booker for allowing the entrance of USA writers.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jul/08/man-booker-peter-carey-julian-barnes

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the rise of the audiobook.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jul/09/easy-listening-rise-of-audiobooks-alex-clark

The link below is to an article reporting on the 2018 Will Eisner Comic Book Awards.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/07/23/2018-eisner-awards-winners/

Emily Troscianko, University of Oxford

Why do you read? Maybe you read to relax after a long day, to learn about unfamiliar people or places, to make you laugh or to let you dream. Maybe you never really ask yourself why, but turn to books out of some vague instinct that they’re what you want or need.

The question of why humans invest such a lot of time and other resources in reading is an interesting one for researchers of both minds and texts, especially when it comes to fiction and poetry, where the answer doesn’t seem as obviously pragmatic as just learning useful facts. Whatever the answer is, it promises to tell us as much about human nature as it does about literature.

For decades now, researchers in cognitive literary studies have been suggesting reasons for why we read fiction. The dominant thinking is some variant on the idea that reading (especially reading narratives, often fictional) is pleasurable because it serves some evolutionarily adaptive purpose, in particular by giving us the chance to hone cognitive skills of one kind or another, free of real world risks. One strand of the general idea that narrative reading may increase our “fitness” is that it may quite literally help us be healthier.

Self-help books are an obvious place to start. There’s a growing body of research on “self-help bibliotherapy” (reading a self-help book, with or without some kind of formal guidance) which indicates that self-help books can sometimes be effective alternatives or supplements to other kinds of therapy.

But very little is known about whether readers respond in clinically relevant ways to poetry, fiction, or other narrative genres, such as memoir. The lack of evidence has not prevented a range of claims and theories from being proposed, and small-scale clinical uses of fiction and poetry by psychiatrists and psychotherapists seem to be fairly widespread.

So is the belief in art’s healing power just wishful thinking, or is there something to it?

The focus of my work is eating disorders. To find out more about the effects of fiction-reading in this context, I set up a partnership with the leading UK eating disorder charity, Beat. We designed a detailed online questionnaire to ask respondents about the links they perceive between their reading habits and their mental health (with a focus on eating disorders). The survey attracted 885 responses (773 from people with personal experience of an eating disorder).

We found that 69% of those with personal experience reported seeking out both fiction and nonfiction to help with their eating disorder, and that 36% had found the fiction or nonfiction they tried helpful. We asked people to rate the helpfulness and harmfulness of different types of text in relation to their eating disorder, and 15% rated fiction about subjects other than eating disorders as more helpful than any other text type. At the same time, memoirs featuring an eating disorder were rated the most harmful text type, with fiction about eating disorders in second place. This suggests a complex set of effects.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/E2QcA/3/

But how does reading fiction actually affect health, positively or negatively? The dominant theoretical view holds that therapeutic effects arise out of a process involving identification (with the character or situation in the text) followed by insight (into the nature of one’s condition). This is perhaps accompanied by some kind of strong cathartic emotional response, followed by a problem-solving stage in which the insights are converted into intentions for personal change. This type of model usually requires that texts should portray situations as similar as possible to the reader’s own, and that they should provide happy but realistic endings.

There are many reasons to question this model. If reading about someone the same as yourself is meant to be therapeutic, what makes it different from, say, rereading your own diary entries? Does the concept of similarity become self-limiting at a certain point, and if so, at what point? And on what dimensions (nature of illness, age, sex, socioeconomic status) is similarity most relevant?

There are also reasons to wonder whether insight is necessarily the main driving force for therapeutic change. In the case of chronic eating disorders, extremely high levels of insight are often coupled with a paralysed inability to act on that insight. So at least among long term sufferers, there may be a more important role for reading experiences that increase motivation or self belief for recovery, rather than providing yet more confirmation of the awfulness of the illness.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/s48tW/1/

The survey findings also direct our attention forcefully to the power of reading to do harm as well as good: one 18-year-old female respondent in recovery from multiple eating disorders described harmful reading matter as “reminding me of why I wanted to starve myself and reinforcing my irrational thoughts”. The testimony on the effects of fiction about eating disorders was overwhelmingly negative; 18 respondents also spontaneously mentioned deliberately “self-triggering”, or choosing to read books they knew would exacerbate their disorder.

Many respondents reported that their eating disorder encourages them to read in such a highly selective way that anything and everything can end up supporting the disordered mindset. Self-perpetuating feedback loops also seem to play a powerful role. If you’re feeling trapped by some aspect of an eating disorder (like low self-esteem), you might be more likely to read a certain type of text, or to read in a particular way (like zooming in on every association of thinness with something positive). This then makes you feel worse (maybe feeling instantly fatter or more determined to lose weight), which in turn encourages more unhealthy reading patterns. These vicious circles can be hard to break.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/prna7/2/

But fiction-reading seems to be one of the things that can break them. Fiction about something entirely unrelated to disordered eating can be stabilising and therapeutic in numerous ways. This can be pragmatic and embodied (allowing regular eating to happen, for example) or broadly existential: exploring alternative worlds, or reminding yourself that your life really could be different. A 27-year-old male in recovery from anorexia described how:

After reading sci-fi my mood is raised and I tend to feel more at peace with the universe, cognitively and imaginatively stimulated and inspired.

![]() So, next time you pick up a book, reflect for a while on your reasons for doing so. And think about whether, when you’re tired or stressed out or indeed more seriously unwell, you find forms of solace, healing, or inspiration in the apparently simple black marks on a white background.

So, next time you pick up a book, reflect for a while on your reasons for doing so. And think about whether, when you’re tired or stressed out or indeed more seriously unwell, you find forms of solace, healing, or inspiration in the apparently simple black marks on a white background.

Emily Troscianko, Knowledge Exchange Fellow at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), University of Oxford

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rebecca Hausler, The University of Queensland and Tomoko Aoyama, The University of Queensland

In our series, Guide to the classics, experts explain key works of literature.

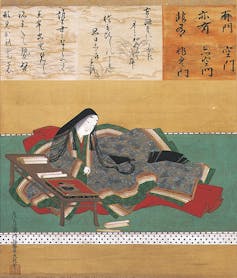

Celebrating its millennial anniversary in 2008, The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari) is a masterpiece of Japanese literature. Completed in the early 11th century, Murasaki Shikibu’s elegant and enchanting prose spans 54 chapters, features some 400 characters and contains almost 800 separate poems. Many consider it to be the world’s first novel, predating most European texts by several hundred years.

Murasaki Shikibu transformed her experiences of courtier life into an intricate narrative fusing fiction, history and poetry. This blending of forms defies simple categorisation under any one genre, though the striking interior life of its characters has led many to term it a psychological novel with prose that feels distinctively modern.

Captivating readers across the English-speaking world from the early 20th century onwards, she has often been compared to canonical artists such as Marcel Proust or Jane Austen for her ability to convey the splendour in the ordinary to her audience.

Consider this passage where a remorseful Genji seeks redemption from his deceased father for his misdeeds against him:

Coming to the grave, Genji almost thought he could see his father before him. Power and position were nothing once a man was gone. He wept and silently told his story, but there came no answer, no judgment upon it. (Chapter 12)

This beautifully captures both the infinite tragedy of losing a loved one, and the abyss of guilt that such unresolved conflicts inevitably impart on us. These words are just as poignant today as they would have been 1,000 years ago.

The author served Empress Shōshi in the Imperial court of Heian (794-1185), situated in modern-day Kyoto. Courtiers were often referred to only by rank, and women were usually known only in relation to their husbands, sons or fathers. Due to such customs her actual name is unknown. Thus Murasaki Shikibu was likely gifted this moniker by her readers; “Murasaki” after the story’s heroine, and “Shikibu” referring to her father’s ministerial position within the court.

Her father, Fujiwara no Tametoki, was a scholar of Chinese classic literature. Despite Chinese being a masculine genre of writing, he nourished his daughter’s keen interest and special talent for it, as well as the more traditionally Japanese feminine writing styles of waka, essays, diary and letters (kana).

Read more:

Why you should read China’s vast, 18th century novel, Dream of the Red Chamber

The Tale of Genji weaves a vivid depiction of aristocratic life in Heian Japan, which centres on the amorous exploits and political gameplay of the nobility. The titular “Shining” Genji is devastatingly handsome, with smooth-as-silk charisma, and a litany of musical, literary and academic skills that “to recount all his virtues would, I fear, give rise to a suspicion that I distort the truth” (Chapter 1).

Throughout the tale, however, he is revealed as an enigmatic but ultimately flawed hero. Rising to the rank of Honorary Retired Emperor (despite never actually reigning), the story of Genji’s success is a multigenerational saga filled with passion, deceit, jealousy, great rivalries and also great intimacies.

Potential readers should be forewarned, however, that many of Genji’s amorous conquests are likely to raise an eyebrow with contemporary audiences. Genji kidnaps and grooms a ten-year-old child bride, before fathering a secret love-child with his stepmother, all the while insistently pursuing a plethora of women in various extramarital affairs.

In a post-#metoo world, it is perhaps difficult to see Genji’s actions as anything but deplorable; however, by Heian standards Genji is lauded as a venerable hero. Controversial themes, including rape, have been condemned by contemporary readings. But the text allows and even encourages many different readings (for example in feminist and parodic fashions), presenting a challenge for contemporary readers and translators alike.

The original Genji text in Japanese poses a number of issues for modern-day readers. Characters were rarely assigned proper names, with designations implied by way of their titles, honorific language, or even the verb form used. The writing also relies heavily on the reader’s pre-existing understanding of courtier life, poetry and history, which is often beyond the contemporary recreational reader.

The first complete English translation was published between 1925 and 1933 by esteemed orientalist scholar and translator Arthur Waley (who translated many other Chinese and Japanese texts such as Monkey and The Pillow Book). Waley’s translation prompted strong reactions from Japanese authors such as Akiko Yosano and Jun’ichirō Tanizaki. Both subsequently completed multiple translations of the work into contemporary Japanese (Yosano’s last translation was in 1939, with Tanazaki’s editions spanning 1939-1965).

There have been a number of recent translations in English, modern Japanese and several other European and Asian languages. Royall Tyler’s 2003 translation provides substantial footnotes, endnotes, illustrations and maps, which offer thorough explanations of the nuances of the text. This makes it suitable for novices as well as the academic reader.

The attention The Tale of Genji has received from translators in recent years speaks not only to the challenges in its translation but also to the beauty and importance of the work itself.

Read more:

How Conrad’s imperial horror story Heart of Darkness resonates with our globalised times

The Tale of Genji is steeped in exquisite images of nature and heavily laden with tanka-style poetry. Descriptions of autumn leaves, the wailing of insects, or the subtle light of the moon work to heighten the complex and nuanced emotions of Murasaki Shikibu’s elegant characters as they traverse the difficult landscape of love, sex and the politics of court life. Such poetic language played a very important role in the communications and rituals of Heian courtier society.

The term mono no aware is often used when discussing The Tale of Genji. This somewhat untranslatable phrase portrays the beautiful yet tragic fleetingness of life. It has deep connections to Buddhist philosophies, emphasising the impermanence of things.

The Japanese celebration of the falling of the cherry blossoms is a good example of mono no aware. Murasaki’s poignant references to the natural world saturate the text and help us reflect on the illusory and sometimes unexplainable nature of life, love and loss.

As a counterbalance to such exquisite imagery, Genji also explores dark and divisive elements. Apart from familial sex, polygyny and sexualisation of children, it includes several key scenes of women experiencing spirit possession or mono no ke. These scenes depict women acting in strange and unpredictable fashions, and suggest that possession actually caused women to become ill and die.

![]() These examples are just a taste of the vast subject matter and textual richness that The Tale of Genji offers readers. Adaptations, parodies and sequels have seen the tale reimagined into film, noh theatre, opera, manga and art. Genji is still very much alive.

These examples are just a taste of the vast subject matter and textual richness that The Tale of Genji offers readers. Adaptations, parodies and sequels have seen the tale reimagined into film, noh theatre, opera, manga and art. Genji is still very much alive.

Rebecca Hausler, PHD Candidate and Researcher in Japanese Studies, School of Languages and Cultures, The University of Queensland and Tomoko Aoyama, Associate Professor of Japanese, The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.