The link below is to an article reporting on Norway’s sensible digital archive program for literature.

For more visit:

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/12/norway-decided-to-digitize-all-the-norwegian-books/282008/

The link below is to an article reporting on Norway’s sensible digital archive program for literature.

For more visit:

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/12/norway-decided-to-digitize-all-the-norwegian-books/282008/

The link below is to a review of Google Audiobooks.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/audiobooks/google-audiobooks-review

The link below is to an article that takes a look at ‘Browsery,’ a new social network for book discovery by Barnes and Noble.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/spotlight-on-android/barnes-and-noble-releases-browsery-a-book-discovery-social-network

The link below is to an article that takes a look at authors who grew to hate their own books.

For more visit:

http://lithub.com/13-writers-who-grew-to-hate-their-own-books/

The joke among poets is that it’s never a good thing when poetry makes the news. From plagiarism scandals to prize controversies, casual readers would be forgiven for thinking the so-called “poetry world” exists in a state of perpetual outrage. In a recent article, The Guardian reported that an essay published in the magazine PN Review “has split the poetry establishment”.

Rebecca Watts’ contentious essay, The Cult of the Noble Amateur, first appeared in the magazine’s print edition in December. In it, she laments social media’s “dumbing effect” on recent poetry, and a “rejection of craft” that is fuelling the success of what she calls “personality poets”. In particular, Watts criticises Rupi Kaur, whose bestselling verse initially found an audience on Instagram, and Hollie McNish and Kate Tempest, whose performances have garnered millions of YouTube views.

To some extent, the only surprise in this latest debate is the wider media interest. Within days, what might have passed like so many online squabbles had prompted further coverage in The Guardian and Bookseller, a segment on Radio 4’s World at One, and an interview with Watts herself on BBC’s Front Row. It’s with no small irony, of course, that the essay’s viral spread came only after it was posted on PN Review’s website, then shared on Facebook and Twitter.

But by focusing on the false opposition of quality and popularity, both sides have been reluctant to see the debate itself as a symptom of the media’s growing interest in the art form. As Watts’ essay admits, poetry is more popular than ever. And over the past few years, news of scandals has increasingly been replaced by celebrations of its renewed relevance.

Within days of the 2016 US presidential election, for instance, the LA Times, CNN, Buzzfeed, Vox and dozens of other outlets were offering what The Guardian called “poems to counter the election fallout”. The Atlantic declared “Still, Poetry Will Rise”, and Wired warned: “Don’t Look Now, But 2016 is Resurrecting Poetry.”

The political impetus for poetry’s media “resurrection” has also fed into a more general sense of its coolness. In the same week that inspired so many election poems, “London’s new generation of poets” were seen “storming the catwalks of Fashion Week”. Meanwhile, Teen Vogue offered a slideshow of young poets who “are actually making the genre cool again” and a Guardian columnist who has written in the past about coconut water trends assured us that poetry is now “the coolest thing”.

For some, this visibility might seem to justify Watts’ worry that poetry like Kaur’s (which featured among The Guardian’s “coolest things”) has become a form of “consumer driven content”. Like some jazz or comic book devotees, certain poetry lovers remain uncomfortable with its widening fanbase. Indeed, in his mapping of the cultural field, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu suggested that poetry’s economic priorities are “reversed”, and that relative obscurity has long been part of its caché.

Desperate to preserve that, perhaps, Watts begins her attack by suggesting that poetry’s “highest ever” sales over the past two years are to blame for declining standards. But she’s not the only one to bristle at poetry’s growing currency, or to assume it proves that “artless poetry sells”.

After Patricia Lockwood’s Rape Joke went viral in 2013, Adam Plunkett, writing for the New Yorker, sneered at her “crowd-pleasing poetry” for its appeal to the “lowest common denominator” online. A similar cycle of praise and censure was repeated last month, when Kristen Roupenian’s short story Cat Person earned a seven-figure book-deal after going viral in the New Yorker itself.

Celebrities trying their hand at verse have been another easy target for the preservationists. The Independent declared that Kristen Stewart had written the “worst poem of all time”, after her piece appeared in Marie Claire in 2014. And in November 2016, Cosmopolitan called on Harvard professor Stephanie Burt to explain why the poems included in Taylor Swift’s new album didn’t really work for her as poems.

![]() Yet, beyond poetry’s appearances at Fashion Week or in financial adverts, there are signs that hang ups over its popular appeal are losing their grip. Beyoncé’s use of Warsan Shire‘s work in 2016’s Lemonade, for example, was met with few claims that it was dumbing anything down. Just as tellingly, the week that saw such heated battles over the PN Review essay also saw the singer Halsey’s moving Women’s March poem go viral to unanimous praise. And there was hardly a peep from the “poetry world”.

Yet, beyond poetry’s appearances at Fashion Week or in financial adverts, there are signs that hang ups over its popular appeal are losing their grip. Beyoncé’s use of Warsan Shire‘s work in 2016’s Lemonade, for example, was met with few claims that it was dumbing anything down. Just as tellingly, the week that saw such heated battles over the PN Review essay also saw the singer Halsey’s moving Women’s March poem go viral to unanimous praise. And there was hardly a peep from the “poetry world”.

JT Welsch, Lecturer in English and Creative Industries, University of York

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

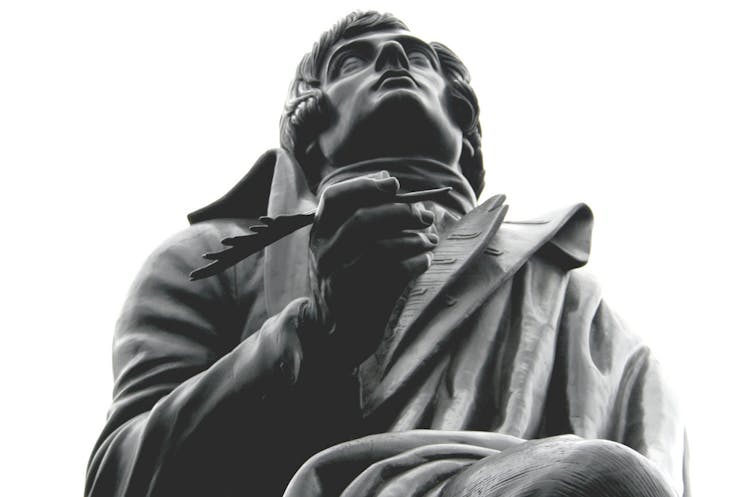

Murray Pittock, University of Glasgow

In the Edinburgh World Heritage website’s story about Scotland’s bard, it notes that when Robert Burns “the ploughman poet” came to the city in 1787, he was “a new boy in town and a great looking heart throb”. It’s a familiar description, dating back to the writer Henry Mackenzie’s review of the iconic Kilmarnock edition of Burns’ poetry in The Lounger for December 1786, describing him as “the heaven-taught ploughman”.

The comparison Mackenzie intends is one with Shakespeare as portrayed by Milton in L’Allegro, whose “wood-notes wild” derive not from education but from inspiration: Burns is to be for Scotland what Shakespeare was for England.

But it was the ploughman label that stuck. Burns is often seen as a “peasant poet”, aligned with the likes of English writer John Clare – and he probably wouldn’t have had it any other way.

During his lifetime, Burns presented himself as “nature’s bard”, ignorant and free of the “rules of Art”. He walked round Edinburgh in farmer’s boots, portraying a deliberately rustic air.

Yet Burns was well read and reasonably educated: he knew the work of Dryden, Fielding, Goldsmith, Milton, Pope, Sterne and many others. He appears to have been influenced both by French bawdy poetry and the troubadour tradition of Provence. In the preface to his Poems (1786), Burns identifies himself as “obscure” and “nameless”, yet cites Virgil and Theocritus.

And Burns certainly wasn’t living in deprivation. He earned much the same from his Edinburgh edition of Poems in 1787 as Adam Smith did from The Wealth of Nations, and in the 1790s his income was as high or higher than Jane Austen’s. It was similar, in fact, to those ministers of the Kirk he liked to bait so much.

He was supported by many wealthy Freemasons. He was the regular correspondent of gentlemen in a strongly class-segregated era, and dined with them. Yet Burns is still often remembered as if he was living on the margins.

This image absolutely suited him: his greatness appeared to be a mystery – and mystery is a lasting source of power. He seemed to have sprung from the soil with no visible means of support. A “celebrity” in the modern sense of a famous person is a 19th-century word: Burns was arguably the first poet to think of himself as a brand.

This self-creation helped to bring him both national and international recognition. In Germany, he came to be seen as both representing the progressive universalism of the radical Enlightenment and a one-stop shop for the folk tradition.

In America he was perceived as the good European, the man of “independent mind” who was a foe to tyrants and an adoptive son of the United States. In the British Empire, he represented the sentiment, communitarianism, egalitarianism and humanitarianism on which many Scots liked to congratulate themselves.

In the USSR, he came to be the “good kulak” (peasant) who would have understood the benefits of collective farming, and the Soviets became the first to issue a commemorative stamp for the poet in 1956.

In China during the Cultural Revolution, he represented the lack of contradiction between the agricultural and intellectual; for Kofi Annan in an United Nations address in 2004, he was the supreme internationalist, the advocate of harmonious neighbourliness worldwide.

Much of this affection stems from the fact that Burns is in many respects the supreme poet of sentiment, certainly in the Anglophone world. We overlook that his paeans to the routine life of rural poverty are distanced by education: in The Cottar’s Saturday Night, he quotes Alexander Pope’s Windsor Forest; in Tam o’ Shanter, he knowingly celebrates sex, drink and dancing in the narrative voice of the Romantic collector of tradition, in a story he invents and sends to such a Romantic collector.

When Burns is knowingly sophisticated, he sometimes appears transparently simple: in Auld Lang Syne the praise of a vanished past, the persisting nature of relationships despite the transience of life, the sugaring of nostalgia, all deflect us from the lack of any promised future. Again we see what we want to see: from It’s A Wonderful Life to When Harry Met Sally and beyond, Hollywood has recognised the song’s extraordinary evocation of sentimental intensity.

Similarly, people often project a political agenda onto Burns that is hard to justify. In To a Mouse, for example, the ploughman does nothing to help the mouse.

Nor is the nature of “Man’s dominion” changed really, despite the ploughman being “sorry” for it. Sorry doesn’t cut the mustard, but the sentiment buttered Burns’s bread and still does worldwide. Most of his supposed politics turns out to be more feeling.

The other element that has done much for the poet’s reputation is the Burns Supper. The first was in Alloway in Ayrshire on July 21, 1801 – celebrations switched from his date of death to his birth later, possibly influenced by the adjacent date of dinners on January 24 for the great British Whig Charles James Fox.

The custom of the Burns dinner or supper spread rapidly. We see it in London in 1804, India in 1812, New York in 1836, and Copenhagen, Paris and Madrid by 1859.

Today, some nine million people attend official Burns Suppers each year alone, and 100,000 Immortal Memories are given. Scotland’s Year of Homecoming was built around Burns in 2009, and in 2018, Scottish Nationalist MSP Joan McAlpine’s parliamentary motion on Burns’ importance to the Scottish economy gained cross-party support.

Burns has been translated several times as often as Byron; he has more statues than any secular figure except Queen Victoria and Christopher Columbus; and is the only person to have appeared on a Coca Cola bottle. He’s a synecdoche of the way Scotland wants to be perceived: humane, egalitarian, caring, international.

![]() “O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us/ To see oursels as ithers see us!” The memory of Robert Burns is indeed immortal. And he knew what he was doing all along.

“O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us/ To see oursels as ithers see us!” The memory of Robert Burns is indeed immortal. And he knew what he was doing all along.

Murray Pittock, Bradley Professor of English Literature, University of Glasgow

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

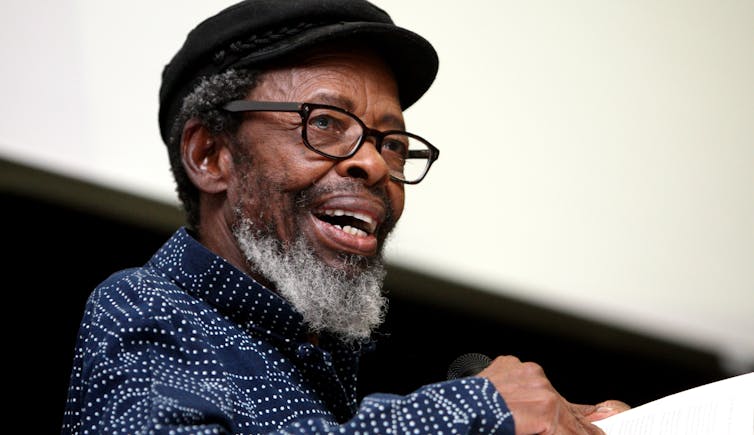

Keith Gottschalk, University of the Western Cape

Memories of Keorapetse Kgositsile (1938-2017), or Bra Willie, as he was affectionately known, are of a poet who always had a smile on his face, who exuded gentleness, and was soft-spoken. He died on Wednesday.

In his schooldays Bra Willie (78) managed to get access to African American poets Langston Hughes’ and Richard Wright’s poems. This was no mean feat in apartheid South Africa when schools for African children either didn’t have libraries or they were poorly-stocked, and African students were denied access to literature deemed to be “seditious”. Even my “whites only” school library had no books with African-American poems, still less the apartheid English setwork books.

His first job was working for a 1950s left newspaper, the New Age, which had strong links to the African National Congress. The apartheid regime banned it in 1962.

In 1962 Kgositsile went into exile in the US. His career flourished in Harlem; he gave numerous readings at African-American jazz clubs, and graduated with a Master of Fine Arts from Columbia University.

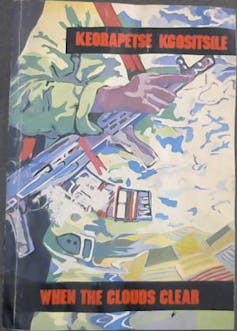

Kgositsile published ten collections of poetry. The first was Spirits Unchained (1969). Perhaps the most influential were My Name is Africa (1971), The Present is a Dangerous Place to Live (1975) and When the Clouds Clear (1990).

In 1975 Kgositsile sacrificed his flourishing career to return to Africa to work for the ANC in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. In 1977 he founded the ANC’s Department of Education in exile, and in 1983 its Department of Arts and Culture in 1983.

He continued to produce poetry and music, melding African and diasporic poetry influenced by jazz.

Kgositsile’s impact on a generation of South African left literary activists during the 1970s and 1980s was immense. Tattered photostats of his work passed from hand to hand were the samizdat of the oppressed under apartheid, which is how we learnt of his poems.

As soon as apartheid censorship ended in 1990, the Congress of South African Writers brought out a selection of his poems When the Clouds Clear. Willie returned to South Africa from exile, and was elected vice-president of the organisation.

Kgositsile wrote of the 1976 Soweto generation who revolted against apartheid, following the imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction.

In our land fear is dead

The young are no longer young …

South Africa’s youth reciprocated this admiration: again and again a youthful poet would recite from memory a Kgositsile poem, mimicking his voice to perfection. They enjoyed doing this to his face as much as in his absence.

In today’s literary establishment, none of the country’s literati command this sort of respect.

He was honoured with the South African Poet Laureate Prize in 2006.

Kgositsile won several literary awards including the Harlem Cultural Council Poetry Award and in South Africa the Herman Charles Bosman Prize, and in 2008 the Order of Ikhamanga (Silver) for

excellent achievements in the field of literature and using these exceptional talents to expose the evils of the system of apartheid.

He was married four times. His wives included Baleka Mbete, a fellow poet and currently Speaker of the National Assembly. He is survived by his fourth wife, Baby Dorcas Kgositsile, as well as seven children and grandchildren.

![]() The author is a published poet.

The author is a published poet.

Keith Gottschalk, Political Scientist, University of the Western Cape

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Dimitra Fimi, Cardiff Metropolitan University

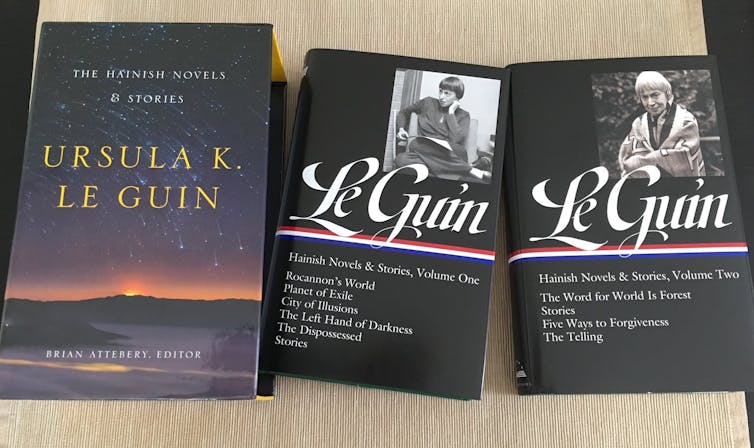

Hermaphrodite beings, dragon women, ambivalent utopias and sympathetic magic. Just a tiny taste of the fantasy and science fiction worlds created by Ursula K Le Guin, who has died at the ripe age of 88.

Le Guin challenged everything that came before and opened up new ways of doing fantasy and science fiction, but she was also a poet, essayist, historical fiction writer, and children’s writer. In 2017 she was voted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters after having won numerous awards, including the Hugo (voted by fans) and Nebula (voted by writers) awards for a single science fiction book twice.

She submitted her first short story for publication at the age of 11, and continued writing prolifically until recently. Her latest book, No Time to Spare: Thinking About What Matters, a collection of essays about everything, from writing to ageing, was published in December 2017.

She was a strong female voice of dissent within male-dominated genres. She challenged race stereotypes in fantasy and science fiction. She had a long-lasting influence on a younger generation of writers. Le Guin’s work has been iconic for a while, studied at universities, loved by readers, praised by critics.

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Le Guin’s parents were anthropologists. Her father, Alfred Kroeber, established the Anthropology Department at Berkeley and her mother, Theodora Kroeber, wrote the biography of the last remaining “wild Indian” in the US. Le Guin’s alternative worlds were anthropological at their core. Instead of medievalesque hierarchies and politics, kings, knights and “small folk”, her worlds are populated by societies that seem tribal. In her Earthsea cycle, magic is “primitive”, ritualistic and shamanic, connected to the power of language. “True names” can summon and control people, animals, matter, and knowing them gives access to power that can become perilous.

In The Left Hand of Darkness, society on the ice planet of Gethen revolves around partly familial, partly tribal groups called “hearths” – and expulsion means sure death from cold. In Always Coming Home, alongside the main narrative, we get ethnographic notes about the customs, myths and rituals of the Kesh tribe.

Principles and beliefs associated with Taoism were also central to Le Guin’s imaginative fiction: non-action, living harmoniously with the self and the universe, respecting the natural rhythms of life. The ying-yang symbol of the balance of opposites is reflected in the “equilibrium” which holds everything together in Earthsea. As Master Hand says: “To light a candle is to cast a shadow.” The same symbol is a powerful metaphor in the harmonious symmetries of The Left Hand of Darkness: male and female, hot and cold, fear and courage.

These elements make Le Guin’s worlds less binary, less based on conflict and resolution, and more mystical, spiritual and – ultimately – refreshingly different to expected norms in science fiction and fantasy. My students often arrive at the surprising realisation that “nothing much happens” in The Left Hand of Darkness. Equally, the Earthsea books don’t focus so much on the standard fantasy trope of defeating a Dark Lord in a great battle, but on changing attitudes and prejudices. The slower pace of Le Guin’s books are part of their success. In a world of fast rhythms and small attention spans, this is a major achievement.

But Le Guin’s beautifully crafted prose also had a sharp edge. She consciously set off to question what came before her in fantasy and science fiction, especially in terms of race and gender. She was outspoken about the “colour scheme” of her Earthsea series. She wrote:

I didn’t see why everybody in science fiction had to be a honky named Bob or Joe or Bill. I didn’t see why everybody in heroic fantasy had to be white (and why all the leading women had “violet eyes”). It didn’t even make sense. Whites are a minority on Earth now.

Ged, the main protagonist of the Earthsea cycle, has copper-brown colouring (emulating the Native American complexion), while the white-skinned Kargs are the main antagonists for most of the series. Similarly, in The Left Hand of Darkness the only character from Earth is a black man, and everybody else in the book is “Inuit (or Tibetan) brown”.

As for gender, is there a better example of a “thought experiment” in challenging norms in science fiction than the genderless world of Gethen in The Left Hand of Darkness? Creating an androgynous people, who only become male or female once a month in order to procreate, gave Le Guin the opportunity to write the iconoclastic sentence: “The king was pregnant”, and to also question how language shapes our prejudices.

Even when many later feminist critics claimed that the book hadn’t gone far enough in interrogating sexism, Le Guin publicly admitted in a revised essay that they were right, and that she had not allowed space for homosexuality in her fictional world. To criticise your own work 20 years after publication takes guts and a unflinching belief in your principles.

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

As for Earthsea, she took it one step further. When it dawned on her that

female magic had been excluded from Earthsea, she returned to her earlier work and changed everything, but without disrupting the coherence and consistency of her originally conceived imaginary world. That is a sure sign of a master in the genre who was able to see her own younger self as entrapped in the cultural and historical moment of writing.

![]() Ursula K Le Guin has taught us a different way of reading, a different way of thinking. If you haven’t read Le Guin yet, may I suggest a short story that encapsulates a lot of her political and social concerns, the masterful (if rather disturbing) The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas. An imaginary world in miniature, and simultaneously a powerful and memorable “thought experiment”. A micro-capsule of Le Guin’s brilliance. She will be missed.

Ursula K Le Guin has taught us a different way of reading, a different way of thinking. If you haven’t read Le Guin yet, may I suggest a short story that encapsulates a lot of her political and social concerns, the masterful (if rather disturbing) The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas. An imaginary world in miniature, and simultaneously a powerful and memorable “thought experiment”. A micro-capsule of Le Guin’s brilliance. She will be missed.

Dimitra Fimi, Senior Lecturer in English, Cardiff Metropolitan University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.