The link below is to an article that looks at Amazon and Audible on there strategy for audiobooks into the future.

For more visit:

http://observer.com/2018/02/amazon-audible-audiobooks-changes-book-publishing/

The link below is to an article that looks at Amazon and Audible on there strategy for audiobooks into the future.

For more visit:

http://observer.com/2018/02/amazon-audible-audiobooks-changes-book-publishing/

Sunanda Creagh, The Conversation

Originally for adults, many fairy tales can be brutal, violent, sexual and laden with taboo. When the earliest recorded versions were made by collectors such as the Brothers Grimm, the adult content was maintained. But as time progressed, the tales became diluted, child-friendly and more benign.

Adults consciously and unconsciously continue to tell them today, despite advances in logic, science and technology. It’s as if there is something ingrained in us – something we cannot suppress – that compels us to interpret the world around us through the lens of such tales.

That’s what we’re exploring on the latest episode of Essays On Air, the audio version of our Friday essay series. Today, Marguerite Johnson, Professor of Classics at the University of Newcastle, is reading her essay Why grown-ups still need fairy tales.

Join us as we read to you here at Essays On Air, a podcast from The Conversation.

Find us and subscribe in Apple Podcasts, in Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Snow by David Szesztay

Mourning Song by Kevin MacLeod

Jack and the Beanstalk by UB Iwerks

Cinderella (1950), produced by Walt Disney

Candle in the Wind/Goodbye England’s Rose by Elton John

P. I. Tchaikovsky: Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, performed by Kevin MacLeod from Free Music Archive.

![]() This episode was recorded by Eddie O’Reilly and edited by Jenni Henderson. Illustration by Marcella Cheng.

This episode was recorded by Eddie O’Reilly and edited by Jenni Henderson. Illustration by Marcella Cheng.

Sunanda Creagh, Head of Digital Storytelling, The Conversation

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Kylie Pappalardo, Queensland University of Technology and Karnika Bansal, Queensland University of Technology

Australian creators struggle to understand copyright law and how to manage it for their own projects. Indeed, a new study has found copyright law can act as a deterrent to creation, rather than an incentive for it.

Interviews with 29 Australian creators, including documentary filmmakers, writers, musicians and visual artists, sought to understand how they reuse existing content to create. It considered issues such as whether permission (“licences”) had been sought to reuse copyrighted content; the amount of time and cost involved in obtaining such permissions; and a creator’s recourse if permission was either denied or too expensive to obtain.

For the majority interviewed, seeking permission to reuse copyrighted content – for example, as snippets of music or video in films, or long quotes in written works – was a source of great frustration and confusion. The process was variously described as “incredibly stressful”, “terrifying” and “a total legal nightmare”.

Problems mostly centred on time delays and financial expenses. Creators found that the paperwork required to request permission was often long, complex and not standard across publishers and other rights-holder bodies. Many waited months for a response to a request; some never received one at all. Many reported feeling ignored and disrespected.

One interviewee, a composer, waited over a year for permission to set poetry to music. The music was due to be performed in a theatre production. The original poet was deceased but his publisher controlled the copyright.

After waiting months and not receiving a response, the composer was forced to painstakingly replace the words to the song with new ones that fit the same rhyme scheme, stresses, cadences and meaning as the original poem. This was a long and difficult process. Roughly a year after the play was staged, permission to use the poem came through from the publishers. By then it was too late.

Licence fees were also an issue for the creators interviewed. Licence fees can be expensive, even for very small samples. Many creators thought that copyright fees demanded for reusing small samples were unfair and stifling.

A filmmaker making a documentary about a small choir in rural Australia could not afford the licence fees to release the film to the public. To show snippets of songs sung by the choir, totalling less than two minutes of copyrighted music in a 20-minute film, with each snippet only seconds in length, the licence fees came to over $10,000. The project was ultimately abandoned because the filmmaker could not raise the funds to cover the licensing fees.

Avoiding and abandoning projects were common reactions to the restraints imposed by copyright law, although a very small number of creators proceeded anyway, hoping to “fly under the radar”.

Some changed projects to try to circumvent copyright restrictions. For example, filmmakers might degrade the sound on their films for scenes where background music might be playing, such as those filmed in a pub or restaurant.

Ideas were filtered out early at the brainstorming stage because they were “too risky” or licensing would be “too expensive”. Some people avoided entire areas of creativity, such as appropriation art, music sampling or documentaries about music or musicians, because it was all just “too hard”.

Court decisions such as the 2010 “Kookaburra” case have further aggravated the problems. In this case, despite significant elements of original creativity, the Australian band Men at Work were found to have infringed copyright of a 1934 folk song, Kookaburra Sits in the Old Gum Tree.

Read more:

The Down Under book and film remind us our copyright law’s still unfair for artists

This case is a classic example of the gap that exists between law and creative norms. The law’s concern, in that case and others, is with what has been taken from an existing work. Creators, on the other hand, most commonly focus on the elements they have added to the work.

The study also highlights creators’ confusion about the scope and application of Australian copyright law. Creators were especially confused about legal exceptions to copyright infringement. In Australia, these are called “fair dealing” exceptions and they are narrow – they apply only to specified purposes (such as for research and study; parody and satire; reporting the news; and criticism and review).

Read more:

Explainer: what is ‘fair dealing’ and when can you copy without permission?

Creators expressed concern about what, exactly, fell within “parody and satire” or “criticism or review”. What do those terms mean when applied to art? Once participant remarked: “Everybody is out there flying a bit blind about this.”

Other countries, including the United States, South Korea and Sri Lanka, have broader exceptions to copyright infringement, which permit reuse for things such as remix or appropriation art, provided that the use is “fair”. These exceptions are generally called “fair use”. Importantly, these exceptions do not require the use to fall within a predetermined category, like reporting the news. Each use is assessed on its own merits.

Courts apply some basic standards in determining what amounts to “fair use”, which include examining the purpose for which an original work has been used; the extent to which it has been transformed; and the extent to which a new work impacts on the market of the original work.

In recent years, the Australian Law Reform Commission and Productivity Commission’s recommendations that Australia adopt a US-style fair use exception attracted significant criticism from much of Australia’s creative sector. Many considered that such an exception would be too broad and too uncertain. However, the study suggests this criticism may be largely unfounded.

The creators interviewed used their own strong sense of morality and fairness to guide what reuse they considered to be acceptable. These principles and norms align quite closely with the factors that courts use in assessing fair use, including how much new creativity has been added to the existing work and whether the new work commercially impacts the existing work in an unfair way.

![]() This new study suggests that more flexibility in the law might actually help to spur the creation of new Australian work.

This new study suggests that more flexibility in the law might actually help to spur the creation of new Australian work.

Kylie Pappalardo, Lecturer, School of Law, Queensland University of Technology and Karnika Bansal, Research Assistant, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at Libre Office 6.0 and the ability to make Epub files with it.

For more visit:

https://the-digital-reader.com/2018/02/01/libre-office-6-0-now-makes-epub-ebooks/

The link below is to an article that looks at how to borrow ebooks from the Kindle Owner’s Lending Library.

For more visit:

https://the-digital-reader.com/2018/02/02/borrow-book-kindle-owners-lending-library/

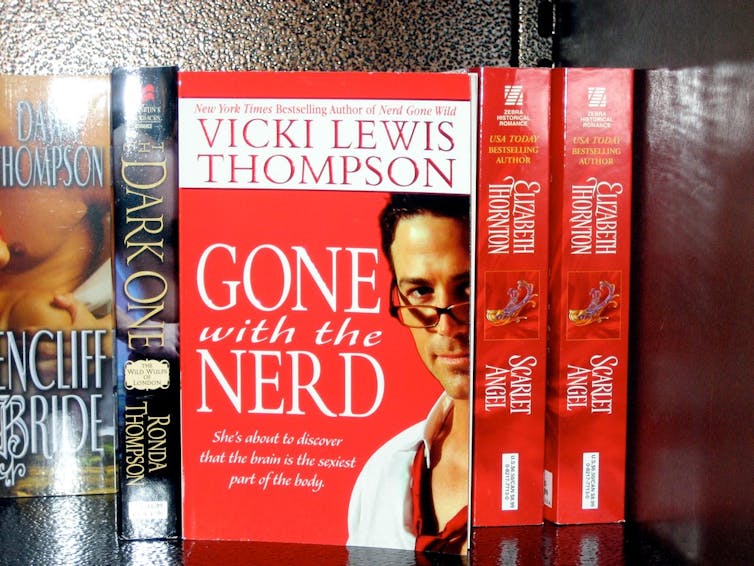

Chris Larson, University of Colorado

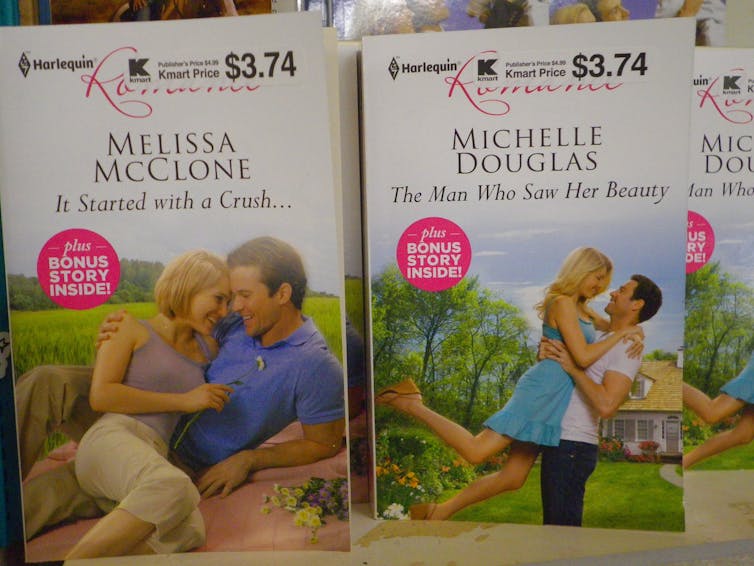

When “Fifty Shades Freed” opens in theaters on Feb. 9, fans will no doubt flock to see bad boy Christian Grey (played by Jamie Dornan) bested by naughty-but-nice heroine Anastasia Steele (Dakota Johnson).

A less racy but equally thrilling story, my research shows, is how romance writers are getting ahead in the digital era.

While economists and labor scholars wring their hands over the rise of the precarious gig economy, these freelancers have developed innovative business practices over the past four decades that have set them up for success in the digital era.

Although few have reached the flabbergasting success of “Fifty Shades” author E.L. James, a former fan fiction writer whose net worth now totals more than US$58 million, I found that the median income for romance authors has tripled in the e-book era. And more and more are earning a six-figure income.

This uptick occurred as other types of writing became less profitable. During the same period, a survey of 1,095 Authors Guild members found that their median income from writing fell by at least 30 percent.

Clearly, romance writers know something that other authors, and many struggling freelancers, don’t. The one-third of American workers toiling in the gig economy can learn a few lessons from them.

Some 57.3 million U.S. workers freelanced in 2016, according to research firm Edelman Intelligence. Economists Lawrence Katz and Alan Krueger found that 15.8 percent of Americans work in “alternative work arrangements” (freelancing, contracting, temp work, etc.), up from 9.1 percent in 1995. In fact, they found that all net job growth in the U.S. from 2005 to 2015 came from such work.

If you’re not already freelancing, you may be soon. Edelman predicts that given current growth rates, more than half of the American workforce will freelance by 2027.

Experts don’t agree whether this trend is good or bad for workers and the economy. The freedom is nice but freelancing often pays poorly.

While few writers are getting rich off books alone – I found that half of romance writers earned less than $10,000 in 2014 – more and more are able to support themselves. While only 6 percent earned at least $100,000 in 2008, more than 15 percent did in 2014. Most gig workers, including authors, patch together a living through multiple occupations.

You might speculate that romance writers’ succeed because smut sells. But that doesn’t explain why romance writers are faring better than their peers with digital sales.

Instead, three surprising practices set romance writers up for success: They welcome newcomers, they share competitive information, and they ask advice from newbies.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/r0E4m/7/

Faced with rejection and ridicule from other writing groups in the 1970s, romance writers formed their own professional association, Romance Writers of America. It now has some 10,000 members.

From its start in 1980, the group embraced newcomers. Unlike other major author groups – and most professional associations – this one welcomes anyone seriously pursuing a career in the field. Newcomers may join once they’ve completed an unpublished romance manuscript.

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Similar groups, including the Authors Guild, Mystery Writers of America and Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, limit full membership to published authors. In some cases, these groups only accept members whose work has been published by specific companies or who have earned a specified amount of money in royalties.

Unlike Romance Writers of America, most traditional guilds, unions and trade associations only admit established professionals.

These barriers to entry can stultify and stagnate industries, especially with today’s transitions. Network theorists Walter Powell and Jason Owen-Smith, for instance, found that the most successful biotech companies in the 1990s formed strategic alliances with newcomers.

This phenomenon isn’t new.

Political science professor John Padgett of the University of Chicago found that upper-crust families in Renaissance Florence who allied themselves with new, upstart families prospered, while members of the elite who shunned newcomers lost influence over time.

A strong tradition of mentoring pervades the culture. Romance Writers of America runs contests for unpublished writers and schedules conference tracks for newbies, and informal Yahoo loops, Google groups and meetups help newcomers get oriented.

These networks proved valuable when new digital self-publishing avenues opened up 10 years ago.

Numerous self-published romance writers, including blockbuster author Bella Andre, known for her Sullivan family books, shared their mistakes and successes with other writers as they tried new digital methods of publishing and promotion. Marie Force, best-selling author of the Gansett Island series, started an online self-publishing advice group. Some authors, like Brenna Aubrey, whose romantic stories are about geek culture, even declare their earnings.

This radical transparency that propelled many romance writers to digital success can work in other fields.

For instance, openly sharing local rates and best practices could prove valuable to workers who find jobs through sites like Upwork and TaskRabbit, many of whom set their own prices.

The openness of romance writers has yielded an unexpected side benefit: access to innovators. The most successful romance writers I studied were experienced authors who asked newcomers for advice.

Using social network analysis tools, my colleague Elspeth Ready and I looked at advice patterns among 4,200 romance writers I surveyed.

While you might presume that novice writers would seek advice more often than anyone else, this wasn’t the case. While 72 percent of unpublished authors in my survey sought advice in the past year, a subset of established writers asked advice just as often. These were established authors interested in shifting to self-publishing.

Many of them did, successfully. I found that, by 2014, traditionally published authors who had added self-publishing to their portfolio out-earned all other romance writers: These so-called “hybrid” authors had a median income of $87,000.

Of course, most writers weren’t earning nearly that much: Half earned less than $10,000 a year. And my survey relied on self-reported income, which can be imprecise. Still, as a whole, these writers saw their prospects improve as the digital gig economy grew and other authors were earning less than before.

![]() At a time when work is becoming increasingly solitary, it only seems fitting that a model involving mutual care and support comes from the freelancers who earn a living from imagining successful connections.

At a time when work is becoming increasingly solitary, it only seems fitting that a model involving mutual care and support comes from the freelancers who earn a living from imagining successful connections.

Chris Larson, Assistant Professor of Journalism, University of Colorado

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The links below are to articles that report on Scrib bringing back unlimited ebook reading and audiobooks.

For more visit:

– http://blog.the-ebook-reader.com/2018/02/06/scribd-brings-back-unlimited-ebook-and-audiobook-plans/

– https://ebookevangelist.com/2018/02/06/scribd-brings-back-unlimited-reading-sort-of/

– https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/scribd-reintroduces-unlimited-audiobooks-and-ebooks

Philip W. Scher, University of Oregon

On Jan. 22, Ursula K. Le Guin died in Portland, Oregon. Since then, much has been written memorializing her genre-defying body of work, her contributions to feminism and science fiction, and her broad interest in human society and government.

But as a cultural anthropologist, I’ve always been interested in the relationship between Le Guin and her father, anthropologist Alfred Louis Kroeber.

Kroeber’s ideas – which had a profound influence on his daughter’s writing – stemmed from an important development in the discipline of anthropology, one that viewed human culture as something that wasn’t ingrained, and had to be taught and learned.

Kroeber’s mentor was a Columbia University anthropologist named Franz Boas. Kroeber was especially drawn to Boas’ newly developed notion of culture and the broader theory of “cultural relativism.”

Cultural relativism emerged in the late 19th century as an alternative to theories like social Darwinism that linked culture to evolution. These theories – widely accepted at the time – tended to rank human societies on an evolutionary scale. Not surprisingly, Western European civilizations were seen as the pinnacle of culture.

But Boas proposed something radically different. He insisted, based on field-based research, that humans live in stunningly diverse cultural worlds shaped by language, which creates institutions, aesthetics, and ideas and notions of right and wrong. He further argued that each society needs to reproduce its culture through teaching and learning.

Kroeber described culture as “superorganic.” According to this idea, the “civilizational achievements” of any group of people weren’t passed down biologically and could only be taught. If we’re deprived of our access to human instruction – books, guides, teachers – we won’t know how to build buildings, write poetry and compose music. Humans, Kroeber knew, are hardwired to create, but there’s no such thing as a “hereditary memory” that allows a people to intuitively know how to recreate specific things.

He told the hypothetical story of a baby taken from France and brought to China. She would, he argued, grow up speaking perfect Chinese and would know no French. His point – as obvious as it might seem today – was that there was no hereditary quality to “Frenchness” that would carry over, genetically, to a child born of French parents.

The idea of culture as “superorganic” says that people are organic lifeforms, like ants or dogs or fish, but culture is “added” to them, which influences their behaviors. Ants and dogs don’t need culture to reproduce their behaviors: Raised in isolation from their own kind, they still do the things they were programmed to do.

Kroeber, along with many of his fellow anthropologists, were drawn to these ideas because they depicted culture as universally human, but not universally rankable, racially predetermined or inherently more or less sophisticated.

For example, it was common in the late 19th century for expansionists to justify their imperialist ambitions with “scientific” evidence that Native Americans were culturally inferior. They pointed to language: Native Americans, they claimed, didn’t have words for the passage of time. For this reason, they couldn’t grasp a complex concept like history.

But Kroeber and his colleagues pointed out the Hopi did have a complex way of reckoning time. They just didn’t count things, like days or hours, using the same terminology they might use to count men, or rocks or clouds, which are objects you can actually see. To the Hopi, a day is in no way like a rock. So it shouldn’t be treated as such.

Kroeber’s peers included African-American anthropologist and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston, Jewish linguist and anthropologist Edward Sapir, and female scholars such as Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead. All grappled with discrimination and cultural denigration.

In response, Kroeber was compelled to write that history, geography and the environment influenced cultural differences. No culture simply emerged naturally.

“Social agencies are so tremendously influential on every one of us,” he wrote, “that it is very difficult to find any test that, if distinctive racial faculties were inborn, would fairly reveal the degree to which they are inborn.”

The only reason, according to Kroeber, that someone would insist on innate differences between human population would be to preserve the status quo: societies built on racial discrimination and colonialism.

Throughout her childhood in Berkeley, California, Ursula Le Guin was exposed to these ideas. They very likely formed the basis of her worldview.

Her writing was never simply about creating a magical or strange world. It was about crafting a laboratory to play with identities – race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality or class – in a way that forced readers to think about how cultural prejudice colored their views of other people.

“Entertaining them is all well and good,” she told New York Times reporter John Wray, “but does it make them think?”

With Le Guin, it always struck me that the point of her imagined universes was precisely to show that nothing human was universal, and that what was “alien” was only a matter of perspective.

In “The Left Hand of Darkness,” Le Guin tackled the idea of gender norms. Here, I think she was channeling Margaret Mead’s breakthrough study “Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies,” in which Mead was able to demonstrate that gender norms can significantly diverge across cultures.

In “The Word for World Is Forest,” Le Guin didn’t simply pen an environmentalist fable about the destruction of a forest and its people. She built off the insights of indigenous scholars like Vine Deloria Jr., who put native peoples’ voices and worldviews at the center of the indigenous rights movement. In “The Dispossessed,” she contrasts the different political systems of two neighboring worlds not to argue which one is best, per se, but to show that in order for these systems to exist, humans need to actively participate in and reproduce them.

In 2015 I planned an anthropology class that I hoped could use speculative fiction and fantasy as a way to understand basic concepts in cultural anthropology. The class was built around Kroeber and Le Guin.

A mutual friend gave my syllabus to Le Guin, and she wrote to me. She suggested some other works to include and seemed to appreciate the concept of the course.

![]() “I think my pa would be tickled,” she wrote, “that he and I have ended up on the same [syallabus].”

“I think my pa would be tickled,” she wrote, “that he and I have ended up on the same [syallabus].”

Philip W. Scher, Professor of Anthropology and Folkore, University of Oregon

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.