Trey Ratcliff, CC BY-NC-SA

Billy J. Stratton, University of Denver

Recent revelations about Hollywood’s culture of sexual harassment and violence might come as a surprise to many Americans.

After all, Los Angeles – home of what some call “the American image factory” – has long carried the allure of glamour, wealth and fame. Beckoned by the iconic Hollywood sign in the Santa Monica Mountains, the city, in many regards, has become synonymous with the American dream.

People familiar with the industry might tell a more complicated story. That group includes writers who have made Los Angeles and Hollywood their subjects: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Nathanael West, Evelyn Waugh, Gore Vidal, Joan Didion and Bret Easton Ellis. All have chronicled a seamier side of the California dream, a world awash with drugs, sex, violence and abuses of power.

So how did so many of us miss this? Could it have anything to do with the fact Americans who read literature recently fell to a three-decade low?

At the very least, the works of these writers show that literature can play an imperative role in our culture – that novels can give us a means of facing difficult issues that many of us may prefer to ignore, or don’t want to believe exist.

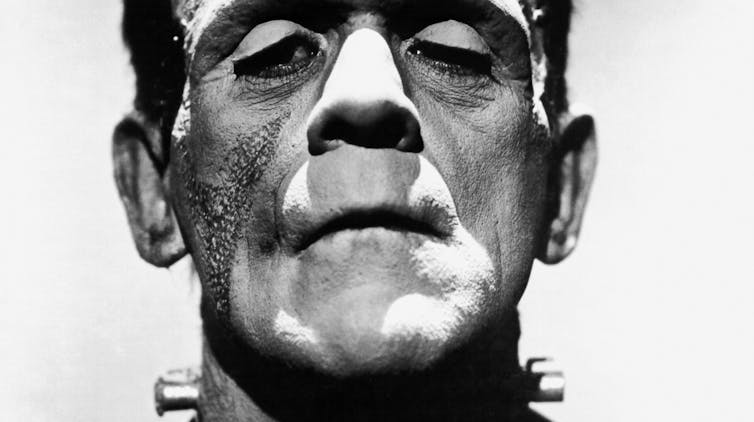

A city of vampires

In numerous novels since the 1930s, Hollywood’s underbelly has been revealed as a landscape rife with peril. And while many writers have explored the vice, corruption and disillusionment at the heart of Hollywood, few have gone deeper into the shadows than Nathanael West and Bret Easton Ellis.

West’s 1939 novel, “The Day of the Locust,” depicts the struggles of Faye Greener, an aspiring actress in pursuit of Hollywood fame and fortune – a dream laid waste by the men she meets along the way, who see her as little more than an object of their desires.

Pursued and stalked throughout the novel, Greener eventually turns to prostitution to make a living. Worse yet, to the novel’s protagonist, she’s the subject of disturbing rape fantasies. The story ends in a frenzy of violence at a Hollywood movie premiere – West’s ultimate denunciation of a culture and a city.

More than 40 years later, the characters of Bret Easton Ellis’s fiction are subjected to almost unspeakable forms of trauma and sexualized violence in “Less Than Zero” and “The Informers.”

In “Less Than Zero,” billboards emblazoned with the words “Disappear Here” loom over the landscape. They’re apparently advertisements that invite a blissful escape to some far-off resort. But for the novel’s main character, they become a menacing warning of a city that devours all who live and work there.

The novel’s main character, Clay, descends into the darkest recesses of this world – a journey to, as he puts it, “see the worst.” And indeed he does.

Although some of the horrors he witnesses occur in back alleys and basement clubs, the most shocking forms of violence – rapes, the viewing of snuff films – transpire at ritzy hotels and posh homes in Malibu, Bel Air and Beverly Hills. We are led to the realization that self-destruction, dehumanization and violence are built into the very fabric of Hollywood’s being.

Meanwhile, the young characters in “The Informers” live in a Los Angeles “swarming with vampires.” Many turn to alcohol, drugs and sex to cope with the depravity of lives that are hopelessly artificial and empty. For some, entertainment has devolved into watching videos of women being terrorized by “near-naked masked men.”

At one point, a main character, the son of a movie executive, meets a struggling actor.

“Unless you’re willing to do some pretty awful things,” the actor says, “it’s hard getting a job in this town.” The reader can almost anticipate the despairing surrender conveyed in his final words: “and I’m willing.”

Other novels, set outside of Hollywood, speak to what can be seen only as an epidemic of sexual violence: Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” Louise Erdrich’s “The Round House,” Frances Washburn’s “Elsie’s Business,” Jessica Knoll’s “Luckiest Girl Alive.”

All hold a mirror to a world that many would prefer not to face.

Literature as ‘equipment for living’

Novels cannot replace the immediacy of the testimony offered by the courageous women who, in recent months, have publicly shared their experiences with sexual violence.

Nonetheless, such works can function as a vital corroboration for the heartbreaking truths that these women have revealed. They give a voice to perspectives that are marginalized and silenced.

The critic Kenneth Burke viewed literature not just as a form of amusement or intellectual reward, but as a way of addressing social problems by teaching, as he put it, “strategies for dealing with situations.”

An implicit element of all literature, he argued, is that it gives readers opportunities to imagine how they’d respond to complicated scenarios, from “what is promising” to “what is menacing” – all from the relative safety of our homes. He observed that readers can gain what he called an “equipment for living,” a means to help navigate our daily experiences.

Recent studies reveal other benefits. One found that deep reading makes us “smarter and nicer,” while another showed that reading literary fiction (as opposed to mass market fiction) helps people develop a greater sense of empathy.

![]() In a country whose people have become increasingly isolated from and suspicious of one another, it’s something we need now more than ever.

In a country whose people have become increasingly isolated from and suspicious of one another, it’s something we need now more than ever.

Billy J. Stratton, Professor of American Literature and Culture; Native American Studies, University of Denver

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.