The link below is to an article that takes a look at one person’s reading life and their reflections upon it.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/02/10/the-journey-of-a-reader-900-books-later/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at one person’s reading life and their reflections upon it.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/02/10/the-journey-of-a-reader-900-books-later/

The link below is to an article that considers reading on an iPhone.

For more visit:

https://ebookfriendly.com/things-learned-reading-books-on-iphone-ipad/

The link below is to an article with some tips on retaining what you read. I’m not sure to the merit of each of the tips, though some are useful – the last is not (in my opinion).

For more visit:

https://www.dumblittleman.com/remembering-what-you-read/

Judith Seaboyer, The University of Queensland

Public anxiety about the capacity of digital-age children and young adults to read anything longer than a screen grab has come to feel like moral panic. But there is plenty of evidence to suggest we must take such unease seriously.

In 2016, the US National Endowment for the Arts reported the proportion of American adults who read at least one novel in 2015 had dropped to 43.1% from 56.9% in 1982.

In 2018, a US academic reported that in 1980, 60% of 18-year-old school students read a book, newspaper or magazine every day that wasn’t assigned for school. By 2016, the number had plummeted to 16%.

Those same 12th graders reported spending “six hours a day texting, on social media and online”.

Read more:

Why it matters that teens are reading less

American literacy expert and neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf describes the threat screen reading poses to our capacity for “the slower cognitive processes such as critical thinking, personal reflection, imagination, and empathy that are all part of deep reading”.

She asks:

Will the mix of continuously stimulating distractions of children’s attention and immediate access to multiple sources of information give young readers less incentive either to build their own storehouses of knowledge or to think critically for themselves?

But rather than taking up defensive positions on either side of the digital-analogue reading divide, Wolf encourages us to embrace both. As parents and teachers we can help our children develop a bi-literate reading brain. There are several ways we can do this.

Reading is a learned skill that requires the development of particular neural networks. And different reading platforms encourage the development of different aspects of those networks.

Screen-reading children, immersed from toddlerhood in the pleasures and instant gratification of skimming, clicking and linking, develop cognitive skills that make them adept power browsers, good at the useful ability to scan for information and analyse data.

Read more:

Three easy ways to get your kids to read better and enjoy it

But Wolf suggests this kind of reading “can short-circuit the development of the slower, more cognitively demanding comprehension processes that go into the formation of deep reading and deep thinking.”

Unless the cognitive skills required for deep reading are similarly developed and nurtured, new generations of readers – distracted by the ready availability of digital information – may not learn to venture beyond the shallows of the reading experience.

Along with others concerned with early childhood education Wolf advises encouraging paper literacy from infancy. She doesn’t recommend forbidding devices. Instead we should regularly turn them off and make the time and space to read books on paper with children.

We can model our own reading practices by setting aside our own smart phones to lose ourselves in a book.

Read more:

Love, laughter, adventure and fantasy: a summer reading list for teens

But how can secondary and tertiary teachers help inexperienced readers? The problem is likely to be aliteracy, meaning students can read but they choose not to because they don’t see it to be important for learning. And because they haven’t read much, it’s hard work. The problem can seem intractable. But it can be done.

My first venture into helping tertiary students read better was a 2011-2013 cross-university government-funded project that set out to foster what we termed “reading resilience”. We found if students were persuaded to prioritise reading as they did a test or an essay, they would invest the time to get into the zone that is the other world of the text.

We complemented complex texts with a guide that encouraged students to think critically as they read and to keep going when the language seemed impenetrable, the narrative incomprehensible (or dull) and the length endless. Or when the siren call of the smart phone became irresistible.

They experimented with switching off their devices for blocks of two hours while they simply read. And they did read.

Students prioritised this difficult work because we rewarded pre-class reading with marks. Some classes uploaded one-page, carefully argued responses; others answered complex feedback-rich quizzes.

I surveyed a large first-year introduction to literary studies at the University of Queensland in 2013 before testing a version of the same “reading resilience” course in 2014. The rise in reading rates was exponential.

The number of students who completed all ten primary texts (including the poem Beowulf and Toni Morrison’s Beloved) more than tripled, and the number who completed the ten accompanying secondary texts (selected chapters from an introduction to literary theory and criticism) went up by more than six times.

Reported student satisfaction for this course from 2008 to 2012 had ranged between 64% and 75%. Once reading resilience was introduced, many complained about the reading load yet the level of overall satisfaction jumped to 86%.

It’s not just readers raised in a digital-age who have difficulty with long-form text. Have you have lost the skill of deep reading? Are you finding it increasingly difficult to stay with, say, a literary novel? You are not alone.

Wolf, who despite having two degrees in literature, confesses to the shocking discovery that recently she found herself struggling to stick with a beloved Herman Hesse novel.

Read more:

5 Australian books that can help young people understand their place in the world

We too can switch off our devices and set aside a space and time to revitalise the neural pathways that once made us immersive readers.

As Wolf argues, the skills of “deep reading” that involve “slower, more time-consuming cognitive processes […] are vital for contemplative life”. Deep readers are likely to be more thoughtful members of the community at a time when good citizenship may never have been more important.![]()

Judith Seaboyer, Senior Lecturer, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wayne Wilson, The University of Queensland

Why does reading in the back seat make you feel sick? – Jane, aged 10, from Coburg North, Australia.

Hi Jane, your question about why reading in the back seat makes you feel sick is a very good one. The answer has to do with our eyes, our ears and our brain.

Reading in the back seat can make you feel sick because your eyes and ears are having an argument that your brain is trying to settle!

Read more:

Curious Kids: Why do our ears pop?

When you’re reading in the back seat, your eyes see that your book is still. Your eyes then tell your brain you are still.

But your ears feel the car is moving. Your ears then tell your brain you’re moving.

Your ears don’t just hear, they help with your balance too.

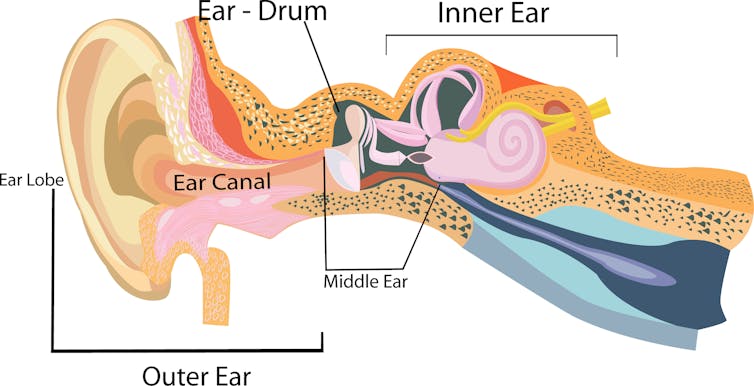

Your ear has three main parts:

Your inner ear contains cells that have hairs sticking out the top. Scientists call these “hair cells”.

Some of these hair cells help us to hear. When sound hits those hair cells, the hairs move and the cells send signals to the brain. Our brains use those signals to hear.

Other hair cells help us to keep our balance. When the car we’re sitting in moves, that movement makes the hairs on those hair cells move too, and they send different signals to the brain. Our brain uses those different signals to tell we’re moving.

Some people’s brains don’t like it when their eyes say they’re still but their ears say they’re moving.

When eyes and ears argue like this, the brain can think that something dangerous might be about to happen.

If this happens, the brain can get the body ready to fight or run away (scientists call this the “fight or flight” response).

One of the things the brain can do is take blood away from the stomach to give to the muscles.

Giving blood to the muscles can help us to fight or run away. But taking blood away from the stomach can make us feel sick.

If reading in the back seat makes you feel sick, you might need to settle the argument between your eyes and your ears.

One way to do this is to stop reading and to look out the car window. This could help your eyes to tell your brain that you’re moving as you see the world whizz by, and your ears to tell your brain that you are moving as you feel the car moving.

But this suggestion won’t work for everyone. Some people will still feel sick when they ride in a car, even if they aren’t reading.

This is because while our eyes and our ears help us to balance, so do our skin and our muscles. This creates many opportunities for arguments that our brain has to settle!

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au![]()

Wayne Wilson, Associate Professor in Audiology, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Amy McLay Paterson, Thompson Rivers University

I don’t understand beach reads. And I’m not the only one. There’s no universal consensus about the category, though the marketing tends to revolve around those books popularly considered disposable, unserious, or at the very least, books “you don’t mind getting wet.”

Last year, I toted Anna Karenina along with me — it got soaked, and I abandoned it in an AirBnB in Dubrovnik, Croatia, after I’d finished reading it. It lasted nearly the whole trip and left a gaping, souvenir-sized hole in my suitcase; it was perfect. So as much as I’d like to dissolve the beach read label entirely, I must also admit I have a type: I want a meaty, absorbing book that takes me further into a vacation by connecting with the cultures that produced it. I want a book that can’t be disposed of, one that will take me somewhere entirely new.

What I really want is to decouple the notion of summer reading as a lifestyle marker of class or gender. If the “pursuit of intellectual betterment” feels inaccessible or off-putting, I would like to propose at least the pursuit of expanding our emotional connections.

In a cultural climate where the limits of empathy are increasingly under a microscope, forging cross-cultural connections feels like a pressing task. Much has been made of the relationship between fiction reading and empathy, but what happens when the limits of our worldview are bounded by the English language? While linguistic diversity is growing in Canada, the majority of Canadians still speak only English at home, and comparatively few books are translated into English. If, as José Ortega y Gasset proposes, reading in translation should transport the reader into the language — and therefore the perspective — of the author, then reading translated works may be one of the best ways to expand empathy beyond the boundaries of language.

I’m not going abroad this summer, at least not physically. I’ll be staying in Canada, with only my books to pull me to other times and places. While in recent years, I’ve focused on keeping up with new releases, this year I’m fixated on atmosphere and transportation, in a mix of old favourites and new-to-me classics from around the world.

I won’t tell you to read Elena Ferrante, because you’ve probably heard that before. Instead, I will be delving into the work of Elsa Morante, a possible inspiration for Ferrante’s pseudonym. Arturo’s Island, originally published in English in 1959, has been published in a new translation by Ann Goldstein (translator of Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels). The novel promises a mix of the remote island setting steeped in Morante’s preoccupation with social issues and the spectre of war.

One of my favourite themes in European literature is that of movement and fluidity, the running sense of unity of purpose amidst myriad diverse pockets of culture. The ubiquity of trains and boats support transcontinental journeys by characters who switch language mid-conversation. Last year’s Man Booker International winner, Flights by Olga Tokarczuk takes traveling and travelers as the subject of its interconnected musings, making it an ideal choice for the vacation headspace. This year’s winner, Celestial Bodies from Oman’s Jokha Alharthi, has an English edition but has not yet been published in Canada.

In my opinion, no contemplation of Pan-European lore can be complete without Dubravka Ugrešic’s Baba Yaga Laid an Egg. Once labeled a witch herself and driven into exile from Croatia, Ugrešic’s take on Baba Yaga explores the shifting nature of popular folklore.

Half of a Yellow Sun by Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is not a translation, but it will take you to a place that only briefly existed: Biafra, a West African state founded in 1967. While the brutality of recent war may not make a particularly appetizing subject for vacation, Adichie contrasts the brutality with sumptuous descriptions of pre-war food and luxury, giving her vision of Biafra the aura of a lost dream. Adichie has referred to the war as a shadow over her childhood.

There are no beaches in Kristen Lavransdatter and many more Christmases than summers, but if you start Nobel Prize-winner Sigrid Undset’s oeuvre now, it may take you until winter to finish it. Set in Medieval Norway, the book follows the titular Kristen from childhood until death, focusing on her tumultuous love affair and marriage to Erlend Nikulaussøn. Tiina Nunnally’s translation, focusing on plain, stripped-down language, presents a change in philosophy from the first English translation that cut large portions of the text and enforced stiff, archaic language absent from the original Norwegian.

Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream is slight in length but packs a heavy punch in both atmosphere and psychological investment. The story of a vacation gone terribly wrong, the novel’s Spanish title closely translates to “rescue distance,” a recurring concept instantly familiar to parents of young children and terrifying as it becomes repeatedly destabilized. Fever Dream is so unsettling that I sometimes hesitate to recommend it, but I’ve found myself repeatedly drawn back to its tantalizing surrealism.

I’ve spent much of my life moving around, and as a recent settler on unceded Secwepemc territory, I want to learn more about the land I live on. In a summer steeped in fiction, Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws by Marianne and Ronald Ignace is the only history on my list, but in many ways it feels similar to the others, reaching out to add a new dimension to a place in which I’m still mostly an outsider. For better or for worse, Kamloops feels the most like itself in summer, the climate wants to have its stories told. It can feel intimidating to contemplate a 10,000 year history I know nothing about, but also comforting and necessary to reach back and hear the tales of the land I now call home.![]()

Amy McLay Paterson, Assessment and User Experience Librarian, Thompson Rivers University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Margaret Kristin Merga, Edith Cowan University

Reading aloud can help young children learn about new words and how to sound them. There’s great value too in providing opportunities for children to enjoy regular silent reading, which is sustained reading of materials they select for pleasure.

But not all schools consistently offer this opportunity for all of their students. We regularly hear from teachers and teacher librarians who are concerned about the state of silent reading in schools.

Read more:

Read aloud to your children to boost their vocabulary

They’re worried students don’t have enough opportunity to enjoy sustained reading in school. This is important, as many children do not read at home.

For some young people, silent reading at school is the only reading for pleasure they experience.

Research suggests silent reading opportunities at school are often cancelled and may dwindle as students move through the years of schooling.

Where silent reading opportunities still exist, we’re often told that the way it is being implemented is not reflective of best practice. This can make the experience less useful for students and even unpleasant.

Yet regular reading can improve a student’s reading achievement. Reading books, and fiction books in particular, can improve their reading and literacy skills.

Opportunity matters too, as the amount we read determines the benefits we get from reading. Regular reading can help with other subjects, such as maths.

So, what should silent reading look like?

Here are ten important things we need to do to make the most of silent reading in our schools.

Enjoyment of reading is associated with both reading achievement and regular reading.

If we want young people to choose to read more to experience the benefits of reading, then silent reading needs to be about pleasure and not just testing.

Young people should not be prevented from choosing popular or high-interest books that are deemed too challenging. Books that are a bit too hard could motivate students to higher levels of achievement.

Students have reported enjoying and even being inspired by reading books that were challenging for them, such as J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings.

Silent reading of text books or required course materials should not be confused with silent reading for pleasure.

Like adults, children may struggle to read in a noisy or uncomfortable space.

Schools need to provide space that is comfortable for students to enjoy their silent reading.

Discussion about books can give students recommendations about other books and even enhance reading comprehension.

But silent reading should be silent so all students can focus on reading.

If students see their teachers and teacher librarians as keen readers this can play a powerful role in encouraging avid and sustained reading.

School principals can also be powerful reading models, with their support of silent reading shaping school culture.

Even when schools have libraries the research shows students may be given less access to them during class time as they move through the years of schooling.

Not all students are given class time to select reading materials from the library.

This is particularly important for struggling readers who may find it hard to remember what they are reading if opportunities for silent reading are infrequent.

These students may also find it difficult to get absorbed in a book if time to read is too brief.

Reading comprehension is typically stronger when reading on paper rather than a screen.

Screen-based book reading is not preferred by most young people, and can be associated with infrequent reading. Students can find reading on devices distracting.

Teacher librarians can be particularly important in engaging struggling readers beyond the early years of schooling. They may find it hard to find a book that interests them but which is also not too hard to read.

Librarians are also good at matching students with books based on movies they like, or computer games they enjoy.

Reading engagement is typically neglected in plans to foster reading achievement in Australian schools.

Practices such as silent reading should feature in the literacy planning documents of all schools.

Allowing students to read for pleasure at school is a big step toward turning our school cultures into reading cultures. Students need opportunities to read, as regular reading can both build and sustain literacy skills.

Read more:

There’s a reason your child wants to read the same book over and over again

Unfortunately, literacy skills can begin to slide if reading is not maintained.

We need people to continue to read beyond the point of learning to read independently, though research suggests this message may not be received by all young people.

Where children do understand reading is important, they may be nearly twice as likely to read every day. So silent reading is important enough to be a regular part of our school day.

This article was co-authored by Claire Gibson, a librarian who’s studying a master in education by research at Edith Cowan University.![]()

Margaret Kristin Merga, Senior Lecturer in Education, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at reading more in 2020.

For more visit:

https://www.goodreads.com/blog/show/1751-super-readers-share-their-best-tips-to-read-more-in-2020

The link below is to an article that takes a look at reading challenges and in particular the Goodreads reading challenge.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/12/05/failing-the-goodreads-challenge/

The link below is to an infographic that takes a look at reading in the 21st century.

For more visit:

https://ebookfriendly.com/reading-21st-century-digital-vs-print-infographic/

You must be logged in to post a comment.