The link below is to an article that takes a look at the book database site, NoveList.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/07/30/best-book-database/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the book database site, NoveList.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/07/30/best-book-database/

Jakob Povl Holck, University of Southern Denmark and Kaare Lund Rasmussen, University of Southern Denmark

Some may remember the deadly book of Aristotle that plays a vital part in the plot of Umberto Eco’s 1980 novel The Name of the Rose. Poisoned by a mad Benedictine monk, the book wreaks havoc in a 14th-century Italian monastery, killing all readers who happen to lick their fingers when turning the toxic pages. Could something like this happen in reality? Poisoning by books?

Our recent research indicates so. We found that three rare books on various historical topics in the University of Southern Denmark’s library collection contain large concentrations of arsenic on their covers. The books come from the 16th and 17th centuries.

The poisonous qualities of these books were detected by conducting a series of X-ray fluorescence analyses (micro-XRF). This technology displays the chemical spectrum of a material by analysing the characteristic “secondary” radiation that is emitted from the material during a high-energy X-ray bombardment. Micro-XRF technology is widely used within the fields of archaeology and art, when investigating the chemical elements of pottery and paintings, for example.

The reason why we took these three rare books to the X-ray lab was because the library had previously discovered that medieval manuscript fragments, such as copies of Roman law and canonical law, were used to make their covers. It is well documented that European bookbinders in the 16th and 17th centuries used to recycle older parchments.

We tried to identify the Latin texts used, or at least read some of their content. But then we found that the Latin texts in the covers of the three volumes were hard to read because of an extensive layer of green paint which obscures the old handwritten letters. So we took them to the lab. The idea was to filter through the layer of paint using micro-XRF and focus on the chemical elements of the ink below, for example on iron and calcium, in the hope of making the letters more readable for the university’s researchers.

But XRF-analysis revealed that the green pigment layer was arsenic. This chemical element is among the most toxic substances in the world and exposure may lead to various symptoms of poisoning, the development of cancer and even death.

Arsenic (As) is a ubiquitous naturally occurring metalloid. In nature, arsenic is typically combined with other elements such as carbon and hydrogen. This is known as organic arsenic. Inorganic arsenic, which may occur in a pure metallic form as well as in compounds, is the more harmful variant. The toxicity of arsenic does not diminish with time.

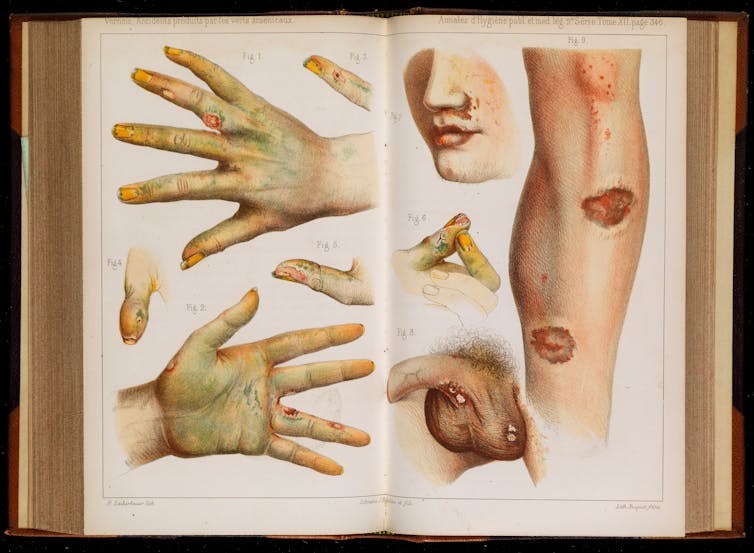

Depending on the type and duration of exposure, various symptoms of arsenic poisoning include an irritated stomach, irritated intestines, nausea, diarrhoea, skin changes and irritation of the lungs.

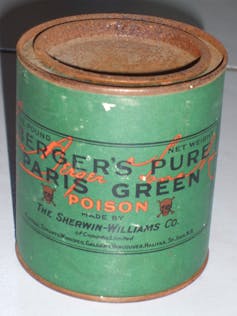

The green arsenic-containing pigment found on the book covers is thought to be Paris green, copper(II) acetate triarsenite or copper(II) acetoarsenite Cu(C₂H₃O₂)₂·3Cu(AsO₂)₂. This is also known as “emerald green”, because of its eye-catching green shades, similar to those of the popular gemstone.

The arsenic pigment – a crystalline powder – is easy to manufacture and has been commonly used for multiple purposes, especially in the 19th century. The size of the powder grains influence on the colour toning, as seen in oil paints and lacquers. Larger grains produce a distinct darker green – smaller grains a lighter green. The pigment is especially known for its colour intensity and resistance to fading.

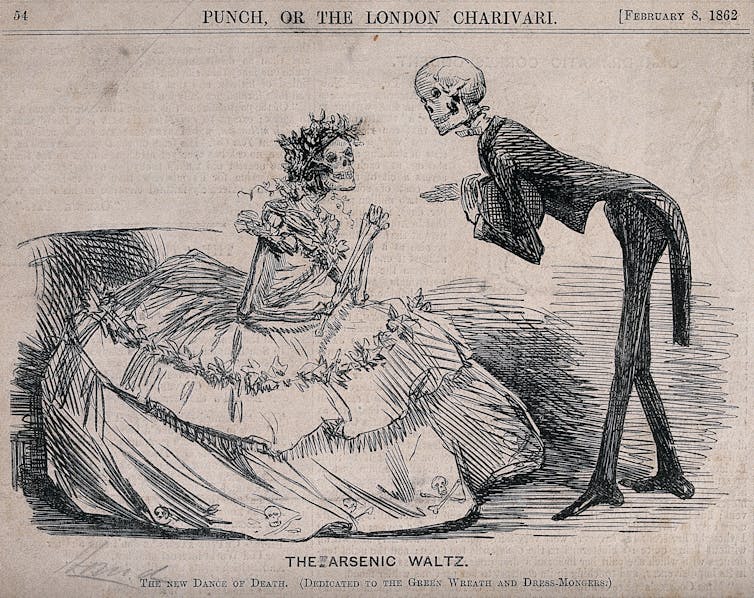

Industrial production of Paris green was initiated in Europe in the early 19th century. Impressionist and post-impressionist painters used different versions of the pigment to create their vivid masterpieces. This means that many museum pieces today contain the poison. In its heyday, all types of materials, even book covers and clothes, could be coated in Paris green for aesthetic reasons. Of course, continuous skin contact with the substance would lead to symptoms of exposure.

But by the second half of the 19th century, the toxic effects of the substance were more commonly known, and the arsenic variant stopped being used as a pigment and was more frequently used as a pesticide on farmlands. Other pigments were found to replace Paris green in paintings and the textile industry etc. In the mid 20th century, the use on farmlands was phased out as well.

In the case of our books, the pigment wasn’t used for aesthetic purposes, making up a lower level of the cover. A plausible explanation for the application – possibly in the 19th century – of Paris green on old books could be to protect them against insects and vermin.

Under certain circumstances, arsenic compounds, such as arsenates and arsenites, may be transformed by microorganisms into arsine (AsH₃) – a highly poisonous gas with a distinct smell of garlic. Grim stories of green Victorian wallpapers taking the lives of children in their bedrooms are known to be factual.

![]() Now, the library stores our three poisonous volumes in separate cardboard boxes with safety labels in a ventilated cabinet. We also plan on digitising them to minimise physical handling. One wouldn’t expect a book to contain a poisonous substance. But it might.

Now, the library stores our three poisonous volumes in separate cardboard boxes with safety labels in a ventilated cabinet. We also plan on digitising them to minimise physical handling. One wouldn’t expect a book to contain a poisonous substance. But it might.

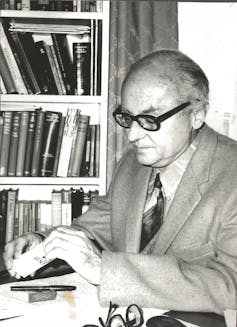

Jakob Povl Holck, Research Librarian, University of Southern Denmark and Kaare Lund Rasmussen, Associate Professor in Physics, Chemistry and Pharmacy, University of Southern Denmark

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article (with embedded video) that takes a look at one of the last remaining chained libraries – at Hereford Cathedral.

For more visit:

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20180706-the-ancient-library-where-the-books-are-under-lock-and-key

Julia Horne, University of Sydney

The Donald and Myfanwy Horne Room will open today in a gracious space in the State Library of New South Wales. One side of it is adorned with objects from the home where I lived with my family, my father Donald Horne (1921-2005), author of The Lucky Country and numerous other books, and my mother, journalist and editor Myfanwy Horne (1933-2013) who wrote as Myfanwy Gollan.

The rest of the room is set aside for study based on ideals of scholarly curiosity, imaginative inquiry and intellectual creativity. As my father wrote shortly before he died, words like curiosity and imagination help “celebrate scholarship and the marvels of the intellectual life more generally”.

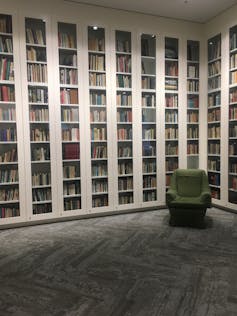

The State Library has selected certain objects from my family home to inspire their scholars and fellows program — an upholstered mid-20th century armchair, a large 19th century pedestal desk and a collection of some 4000 books.

The armchair, now upholstered in a dark green material over the original knobbly grey fabric, was acquired by my parents to furnish their first home in 1960, a small, rented two-bedroom garden flat in Sydney’s leafy Double Bay.

It was on this chair, in 1964, that my father sat “pen in hand, pad on knee”, as my mother later wrote, “to write The Lucky Country”. I was too young to remember this act of defiance, as some now see it — after all, surely a serious writer sits at a desk. The act itself was born out of necessity, and only later became symbolic (at least in my parents’ minds) when my father acquired a new string to his professional bow — a writer of books.

Read more:

Donald Horne’s ‘lucky country’ and the decline of the public intellectual

In the early years of their marriage in their small flat, my parents had a choice: to turn a spare room into a dining room or into a study with a desk. A dining room it became, and instead of a desk, they purchased a mahogany dining table. Not only does this choice show the importance of the dining room in middle class Australia, but also the consequence my parents gave to the well-planned dinner party. My father even brought to his marriage several signature dishes, including a delectable petit pois dish I still cook to this day as well as Ted Moloney’s and George Molnar’s Cooking for Bachelors (1959).

The Lucky Country came out of formal quests for knowledge, but also arose out of congenially robust discussion around the dining room table. My mother acquired a new professional role, as editor of all her husband’s books and much of his other published writing. The armchair, then, marks a state of transformation in my parents’ working and personal lives and in their home, as an enduring workshop of ideas.

In 1966, we moved from our rented flat to our new house, a late 19th century two-storey terrace with room for both a dining room and a study. It remained my parents’ home for the rest of their lives and was not sold until 2015. The spacious, high-ceiling upstairs room at the front was soon furnished as a writers’ study.

Book cases graced either side of the fireplace, one with a small built-in desk for my mother to work at on her typewriter. The French doors leading on to the front verandah were shaded by heavy, satin, mustard coloured curtains. The centrepiece was the large, 19th century pedestal desk chosen by my mother. Placed in the middle of the room at a slightly raffish angle, my father savoured the room as a place to write, surrounded by bookcase-lined walls.

As he later wrote, “sitting at the desk Myfanwy had chosen for me became one of our essential ceremonies” of intellectual life together. “My writing came from a joint workshop of which she was a part. Not only the dinners and lunch parties that helped keep things going: without her emotional support and intellectual support I don’t know that I would have ‘become a writer’.”

Books that influenced my father’s writing and thinking are now displayed in beautiful glass cabinetry in the State Library. You can peruse the spines for a quick trip through 20th century ideas, global politics and history, its revolutions, art, political philosophy, sociology. Well-thumbed copies include A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by the 18th century advocate of women’s rights, Mary Wollstonecraft, and The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies by the 20th century cultural theorist, Roland Barthes, for its critique of bourgeois culture.

Many of the books include his annotations — paper clips, discrete dots, vertical lines and squiggles — making it possible to trace some of what inspired his own social and political critique. The English translations of the writings of the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, for instance, were marked up for his favourite passages on hegemony, “common sense” and the idea that we are all intellectuals. They represent, in many ways, his scholarly footnotes.

“I’ll just go to the study to look it up,” is a refrain I often heard from my parents. Rather than reconstruct their study, the artefacts in the State Library’s Donald and Myfanwy Horne Room have been chosen to continue the intellectual pursuit of conversation and ideas.

![]() You can work at the desk, sit in the green armchair and — by application to the librarian — peruse the books and decipher the scrawls left by my father. These objects are not only tokens of two productive writing lives, but an inspiration to future generations who believe that books and ideas matter.

You can work at the desk, sit in the green armchair and — by application to the librarian — peruse the books and decipher the scrawls left by my father. These objects are not only tokens of two productive writing lives, but an inspiration to future generations who believe that books and ideas matter.

Julia Horne, University Historian and Principal Research Fellow, History, University of Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the libraries of Finland.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/may/15/why-finlands-cities-are-havens-for-library-lovers-oodi-helsinki

The link below is to an article that takes a look at secret libraries of history.

For more visit:

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20160819-the-secret-libraries-of-history

The link below is to an article reporting on flood damage to the Australian National University’s Chifley Library in Canberra, Australia.

For more visit:

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-03-02/anu-staff-begin-urgent-salvage-job-of-books-at-chifley-library/9500414

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the latest news on the Internet Archive & Open Library controversy concerning ‘piracy’ claims. Note, this article is from someone clearly in the anti-Open Library camp.

For more visit:

https://the-digital-reader.com/2018/02/22/internet-archive-ignores-dmca-notices/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the history of book acquisition for the world’s libraries throughout history.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/acquiring-books-for-the-greatest-libraries-in-the-world/

The link below is to another article taking a look at the National Library of Norway and its digital archive program.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/national-library-of-norway-digitizes-250000-ebooks

You must be logged in to post a comment.