Leigh Ann Wheeler, Binghamton University, State University of New York

Most memoirs are soon forgotten.

A rare exception is Anne Moody’s “Coming of Age in Mississippi,” which was published in 1968. It spoke to the day’s pressing issues – poverty, race and civil rights – with an urgent timeliness.

Fifty years later, the book still commands a wide readership. Read each year by thousands of high school and college students, it remains a Random House backlist best-seller – a title that continues to sell with little to no marketing.

As I research Anne Moody’s life for my upcoming biography, I often wonder what her memoir’s continued popularity means. Does it signal dramatic progress on race relations in the U.S. – or does it instead show us that, as former Sen. Ted Kennedy wrote in 1969, “If things are somewhat different, then they are not different enough.”

Till’s death opens Moody’s eyes

Written when Moody was 28 years old, “Coming of Age” is a gripping story. In spare, direct prose, she takes readers into the world of African-American sharecroppers in the Jim Crow South. As a child, she chopped and picked cotton, cleaned houses for white people, and wondered why whites had better everything – better bathrooms, better schools and better seats in the movie theater.

That mystery remained unsolved when, in 1955, Moody learned that white men had killed a black boy her age just a few hours’ drive north. The killing felt personal.

“Before Emmett Till’s murder, I had known the fear of hunger, hell, and the Devil,” she wrote. “But now there was … the fear of being killed just because I was black.”

Closer to home, whites ran her cousin out of town, brutally beat a classmate, and burned an entire family alive in their home. Amid such horrors, Moody feared a nervous breakdown.

But she resolved to resist.

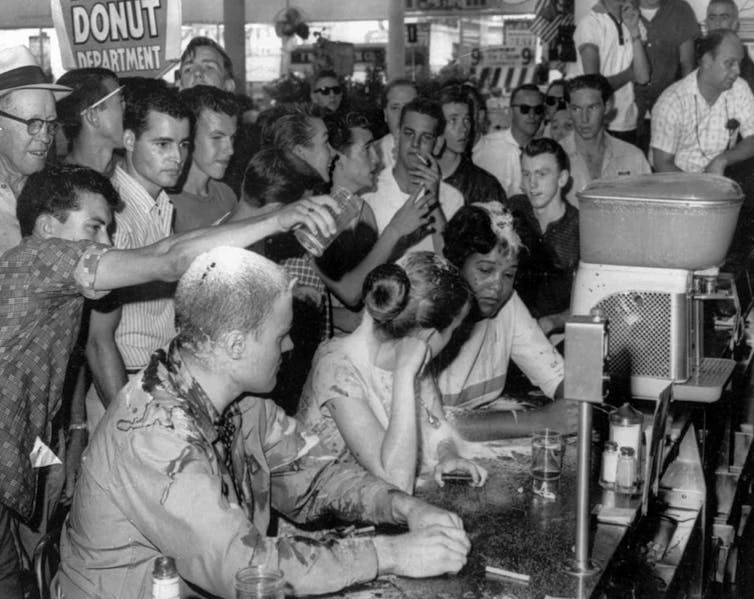

In 1963, Moody became infamous in Mississippi after she challenged racial segregation in what would be the era’s most violent lunch-counter sit-in. At the Woolworth’s in Jackson, Mississippi, white men shoved Moody off her stool, dragged her across the floor by her hair and, when she crawled back, smeared her with ketchup, sugar and mustard.

Photographer Fred Blackwell captured a now-iconic image of this day, with Moody seated in the middle.

Fred Blackwell/Jackson Daily News, via Associated Press

In the early 1960s, Moody worked tirelessly as an organizer for the Congress of Racial Equality in Canton, Mississippi. But after facing daily death threats, she fled to the North, where she moved from city to city, raising money for the movement.

At each stop, she described what it was like to come of age, as a black woman, in Mississippi. At one, she shared a stage with baseball great Jackie Robinson, who urged her to write down her story.

So she did.

Readers react

After “Coming of Age in Mississippi” was published, the response was split.

Some readers viewed the book as – in the words of one reviewer for The New Republic – a “measure of how far we have come.” To them, the worst of racism was over, and Moody’s account served as a stark reminder of how bad things once were.

Dell

Others, however, read Moody’s experiences of racism as simply one chapter in a current and ongoing struggle – “the sickening story of the way it still is for thousands who are black in the American South,” as Robert Colby Nelson wrote for The Christian Science Monitor.

Massachusetts Sen. Ted Kennedy read it both ways.

He called the memoir “a history of our time, seen from the bottom up, through the eyes of someone who decided for herself that things had to be changed.” Still, he regretted that the book did not mention recent advances, like the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which enabled the election of several black public officials in Moody’s own hometown.

Meanwhile, for decades, Southern media outlets and public institutions shunned “Coming of Age in Mississippi” and Anne Moody herself. Hostile whites in Moody’s hometown of Centreville, Mississippi even threatened to kill her if she ever returned.

How much has really changed?

By contrast, today, “Coming of Age” shows up on high school and college reading lists throughout the South, and Anne Moody appears among 21 authors pictured on the Mississippi Literary Map. Her crumbling childhood home sits on the recently renamed Anne Moody Street, and Anne Moody Memorial Highway now connects Centreville and Woodville, the town where she graduated from high school.

In Moody’s day, local public officials were all white. Now they more closely reflect the county’s 75 percent black population.

In 1963, Moody mourned the assassination of her beloved colleague, Medgar Evers, president of the state National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and watched in horror as local whites refused to convict his murderer. Thirty years later, Byron De La Beckwith was finally convicted of homocide and imprisoned for life. Today, visitors who fly into the Mississippi state capital, land at Jackson-Evers International Airport.

These shifts make “Coming of Age” seem, to many readers, an inspiring account of survival, resistance and victory.

But to others, the book is anything but a triumphalist story. Instead, its lessons are grim: In retrospect, civil rights victories seem superficial, while the brutal poverty and racism Moody described endures.

Compared to whites, black people in the U.S. are more than twice as likely to die in infancy, three times more likely to be poor, three times more likely to be killed by police, five times more likely to be imprisoned and seven times more likely to be murdered. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was gutted by a 2013 Supreme Court decision that emboldened states around the country to create new restrictions that prevent black citizens from voting.

Anne Moody was one of the lucky ones. She graduated from college, moved north and published a best-selling memoir.

But despite the accolades, television appearances, radio interviews and speaking engagements, she could never really escape Jim Crow Mississippi. It had deprived her of her family and a place to truly call home.

“Coming of Age” ends with Moody listening to civil rights workers sing the anthem, “We Shall Overcome.”

“I wonder,” she wrote. “I really wonder.”

Fifty years later, many of us are still wondering.![]()

Leigh Ann Wheeler, Professor of History, Binghamton University, State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.